My Introduction to My Class on "New Deal & Neoliberal Orders"

A cleaned-up rough transcript of what I said at the start of class 2023-04-19 We...

The New Deal & Neoliberal Orders: Introduction:

We decided at the start dedicate a couple of weeks to discussing political economy, not necessarily in the grand sense. Political economy papers in economics can be narrow studies of interest groups and the exertion of political power to gain income and resources. Political economy papers in economics can delve into deep theoretical concepts about how humans associate in a game theory context, given various endowments, potential threat points, and the desirability of achieving cooperation. However, there is a middle ground. That middle ground considers how our government is structured as it manages our economy, and how the government's management of the economy has evolved over history. This is a topic that I explored extensively in my 600-page book, Slouching Towards Utopia <bit.ly/3pP3K>.

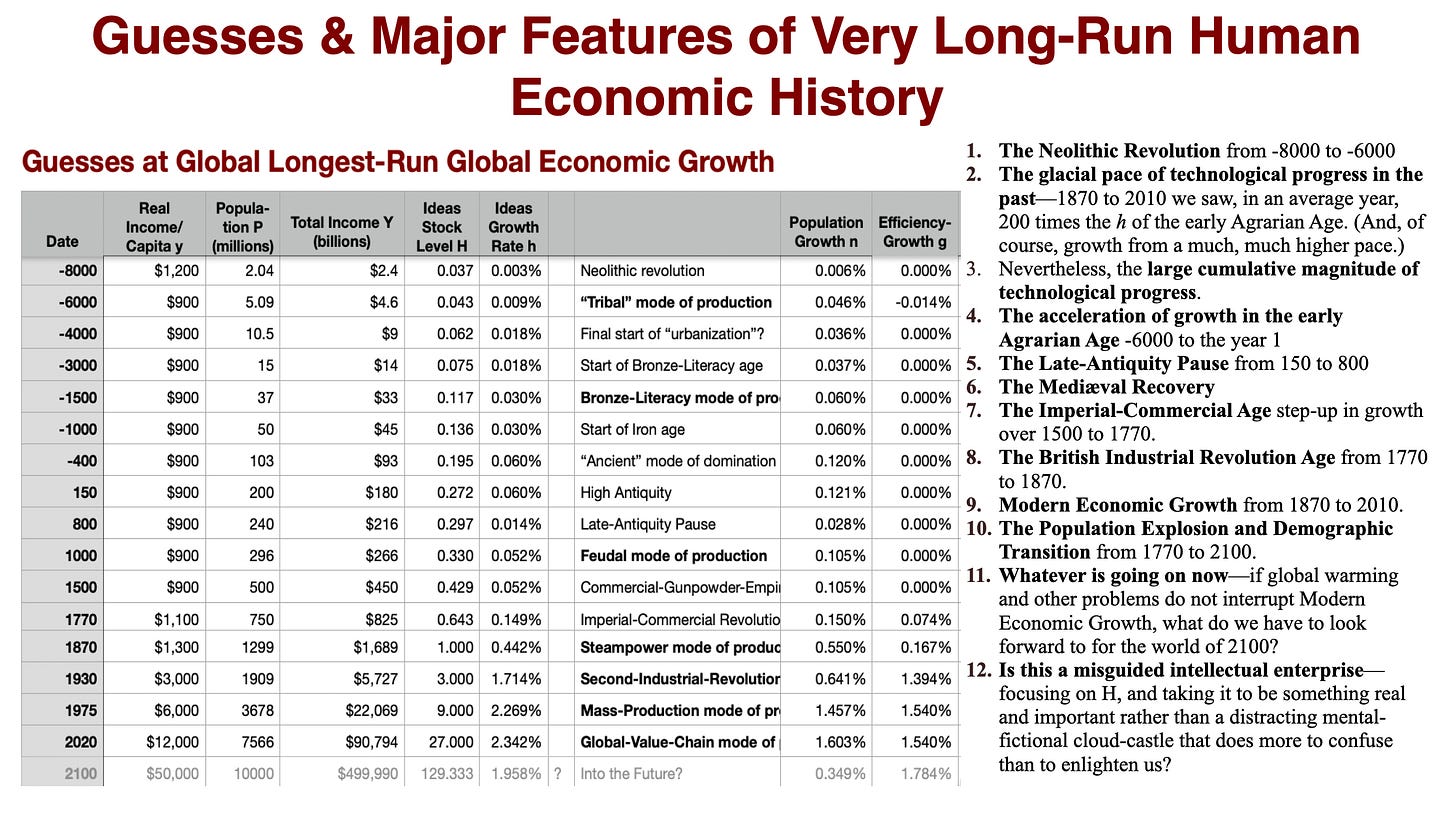

I should start by saying that it was not my original plan to write such a book. The book manuscript did not start as a work about the political economy of the world since 1870, focusing on the global north. Instead, it began as an examination of taking as an organizing frame the idea that the hinge of history was 1870. That date marked the transition from a time when the rate of global technology growth was so slow that it was nearly entirely consumed by population growth and increased resource scarcity, keeping humanity in poverty, to a post-1870 era which Simon Kuznets first called Modern Economic Growth. In the Modern Economic Growth era, fertility was bound to lose its race with technology, and so humanity began to grow wealthier. Since 1870 humanity has grown far wealthier. Income and wealth is appallingly unequally distributed worldwide. Nevertheless, the average person today has ten times the material wealth and the real income of the average person as of 1870.

Starting from this idea that 1870 was truly the hinge of history, the book was then supposed to make four explorations: (a) the workings of a pre-1870 economy and society, (b) the reasons behind the transformation in 1870—why then? why not earlier? and why at all?—the industrial and sectoral details of the process of Modern Economic Growth, and the political-economy consequences of humanity's rapid ascent to previously unimaginable wealth.

However, as I wrote the book, the topic drifted. I became increasingly focused the contrast between the rapidly growing cornucopia of produced commodities on the one hand and our collective failure to equitably distribute that cornucopia or to use it wisely for the well-being of society. Despite the massively increased resources and enormously increased life expectancy we enjoy today, people today do not live in anything near to utopia. We still are hag-ridden by anxiety, violence, and inequity. Clearly, mal-distributed material wealth alone is not enough to solve society's problems. The question we need to understand is: Why not?

For the next two weeks, the last two weeks of the course, we will discuss the rise and potential decline of that Neoliberal Order which has shaped the global north's economies and societies since around 1980. Our discussion will be based on the assigned excerpted chapters from Gary Gerstle's book The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order and my book Slouching Towards Utopia.

The pace of change in technology, modes of production, and social organization since the year 1000 has been remarkable. And in each era the way people work has taught people different lessons about how society should be organized, and has imposed different constraints on what modes of organization people will accept.

The pace of change since 1870 has been particularly significant, in that it has meant that we have had to to rewrite society's organizational software on top of the changing technological productive hardware every 40 years. And we have had to do so without a clear idea of what will fit and what will not. Moreover, the situation at any time is confused, with a variety of surviving elements from previous eras still hanging on.

The socialists of the late 1800s, led by Friedrich Engels, argued that the mode of production would ultimately determine society. In doing so, they were following in the footsteps of arguments made by Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson. But with the rapid pace of change since 1870, can we say that? Is there enough time for the "last instance" to come in which society finds a pattern that fits with the underlying technological foundations of society? That, I think, is an open question.

Between the solidification of imperial-commercial society and the coming of steampower society there were at most two centuries. Steampower society was not socialist. The socialists of the late 1800s said that this was simply because there had not been enough time for the revolution to come, and it was coming. But they were wrong. Steampower society never became socialist. And technology moved the mode of production on to that of applied science society. Since then, there has never been enough time for enough social experiments to be tried and failed and thus for the underlying logic of the economy to make itself felt and drive society to a pattern that "fits" it. As a result, there is little sense in which the political-economy system of governance over the market and society fits with the technological underpinnings.

This is the framework from which I approach our topic, and from which I read Gary Gerstle's book, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America in the World in the Free Market Era.

The introduction to the book asserts that after 2010 we see the beginning of the end of the "Neoliberal Order". It defines a "political order" as: a constellation of ideologies, policies, and constituencies that dominate, so much so that even its opponents find that they have to borrow their rhetoric and accept its terms. One example if this is Dwight D. Eisenhower in the 1950s, claiming he could manage the New Deal order better than Democrats. Another example is Bill Clinton in the 1990s, saying the age of big government was over.

Gary Gerstle and Steve Fraser created this concept of a political economy order. They used it to analyze the rise and fall of the New Deal Order from 1930 to 1980. Why did the New Deal Order rise? It was forged by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the crisis of the Great Depression. Why did the New Deal Order fall. Gerstle and Fraser saw many sources of discontent—racism, over-bureaucratization and inefficiency, and a feeling that ossified institutions were limiting possibilities for human freedom. sources of discontent.

Why did the Neoliberal Order rise? It was driven by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. It was solidified in the 1990s with Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, who represented New Democrats and New Labour. In the 2000s, George W. Bush attempted to spread the neoliberal order through the Washington Consensus. Would the Neoliberal Order have risen without the political talents of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, the luck that kept them in office, and then the fall of socialism in 1990 that they took credit for? Perhaps, and perhaps not.

The Neoliberal Order began to decline due to cultural conflicts, and the Great Recession and the inadequate response of the Obama administration to it.

So, what do people think of this thumbnail sketch of big history, in which Gary sets the rise and fall of the Neoliberal Order in the introduction to his book? Does it seem accurate, at least as applied to the global north, the United States, or perhaps the United States north of the Mason-Dixon line? Or does it seem to miss important aspects that should be included? I'm interested in the dichotomy and explanations of the neoliberal order between, on one hand, Robert Gordon's productivity-centered explanation focusing on the crisis of profitability, and on the other hand, more social or political explanations like the civil rights movement and May '68 in France?

I guess There is no way to get you to use a different wore than "Neo-Liberal." It just seemed like the perfect word for a mid-course correction to US "Liberalism" which did not pay enough attention to long term growth and the ways that budget deficits, and failure to use Pigou taxes (or at least regulations using cost-benefit analysis with the social cost of externalities embedded in the parameters) to correct externalities hampered it. True, that additional redistribution was not part of the idea, but using more explicit distribution to buy political support for more growth-promoting policies.

How sad that the word came to mean tax cuts for the rich and deficits. How tragic that while this "Neoliberalism grew up so did the thicket of land use and "safety" regulations.

The political economy question is how did what came to be called "neoliberalism" go so badly off track from what it could have been? And how do we get it back on track?

I've been a fan of Martin since the World Bank. I'm going to listen as soon as I get a new cell phone. Ezra is the one policy podcast that I'll listen to even though I can't comment on it.