Noah Smith: Review of “Slouching Towards Utopia” at "Noahpinion"

June 12, 2022

Brad DeLong tells his story of the 20th century.

“It’s beautiful…even if it’s where everybody died.” — Nakagawa Noriko

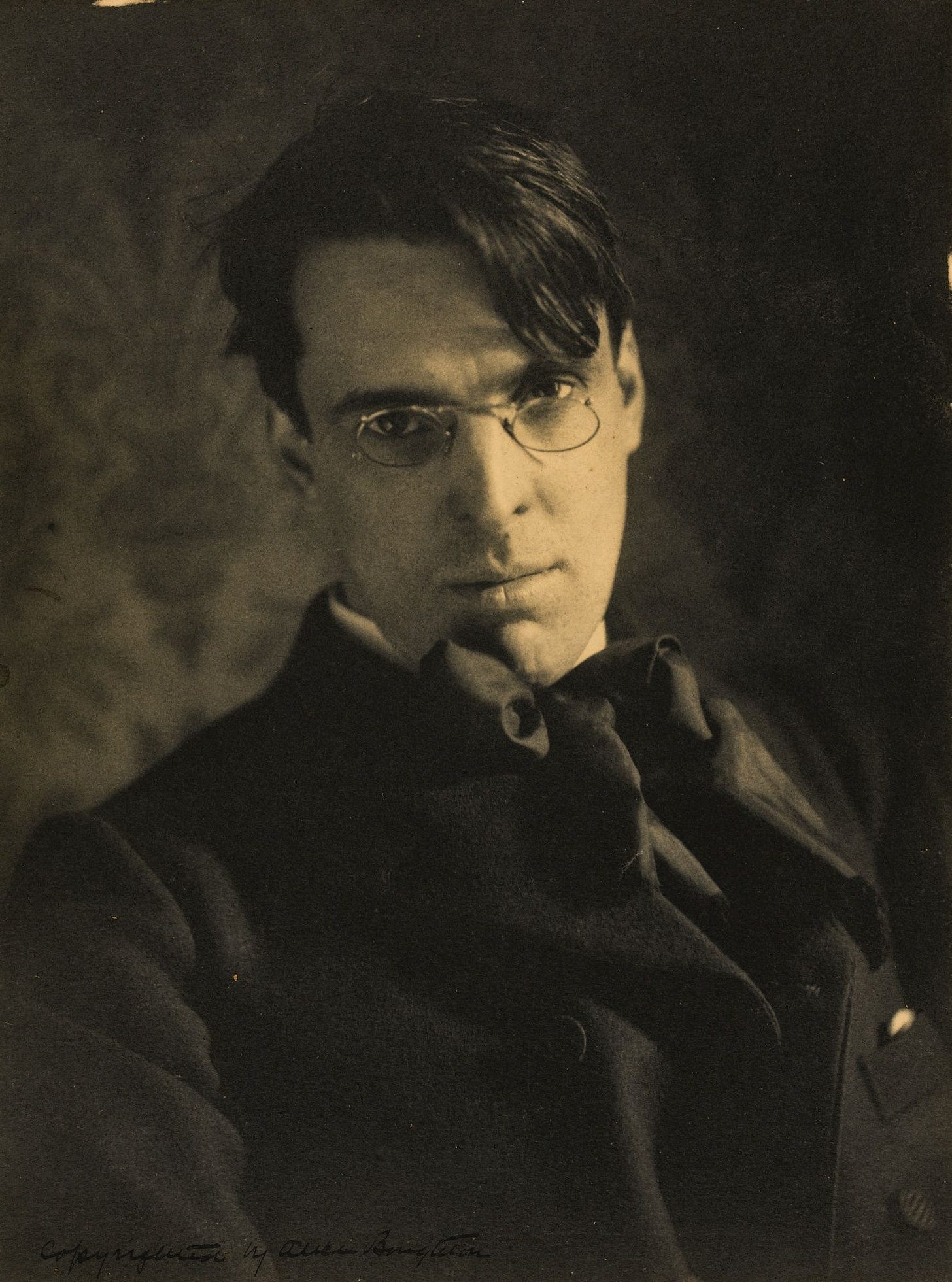

This may actually be the first book review I’ve done before a book has actually been released! Fortunately, I was able to secure an advance copy of the book from my podcast co-host, Brad DeLong. The book comes out September 6th, so hopefully this review can tide you over until then!

Brad DeLong has an encyclopedic command of modern economic history, and an inimitable writing style — it was his blog, back in the mid-2000s, that first inspired me to want to become an econ blogger myself. Reading his book will immerse you in the DeLongiverse — the swirl of fun facts, key phrases, and unifying narratives that comprises DeLong’s brain. It may feel a little strange at first, but once you get used to it, it’s a rewarding experience.

But although DeLong is an economic historian, Slouching Toward Utopia is only partly an economic history book. Mostly, it’s a political-economic history book. There are many books about why the world industrialized and got rich — Mark Koyama and Jared Rubin’s How the World Became Rich, Gregory Clark’s A Farewell to Alms, Joel Mokyr’s A Culture of Growth, Robert Allen’s The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, and Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth, to name just a few. But Slouching Toward Utopia is only slightly about how the world became rich; it’s mostly about what humanity decided to do with the riches it received, and what sort of systems it developed to try to keep growth going. In other words, it’s about political economy.

Why did the world become rich? DeLong argues that only after 1870 did technological progress accelerate to the point where it managed to outstrip human population growth, thus freeing humanity from Malthusian constraints. He attributes this acceleration to three key innovations: the industrial research lab, the modern corporation, and steamship-driven globalization. I would have liked a bit more definitive proof that these were the key causal factors, but DeLong’s arguments in favor of them are fairly persuasive.

With these pieces in place, DeLong shows that total factor productivity — which he calls the “value of knowledge index” — accelerated dramatically right around the time that these things appeared. That acceleration, according to DeLong, continued up until the mid-2000s; thus, he conceives of 1870-2010 as a “long 20th century” characterized by rapid productivity growth and the social and political upheavals it caused.

Most of the book is actually focused on those political upheavals. DeLong’s “long 20th century” saw the development of various ideologies, including liberal democracy, free-market libertarianism, communism and fascism. This was completely natural; thanks to rapidly accelerating growth, humanity was rapidly confronted with newfound wealth beyond their previous imaginings, new possibilities for social organization, new problems, new opportunities, and new distributions of economic power. Of course there were going to be lots of big ideas for how to handle all this, and of course some of those ideas were going to be crazy and bad.

DeLong narrates the rise and (sometimes) fall of these ideas through the lens of two 20th century political-economic thinkers — Friedrich Hayek and Karl Polanyi. Hayek is a market fundamentalist, who basically argues that markets are the best that society can do. Polanyi argues that markets need to be tempered by social protections, in order to protect certain universal values — job security, decent wages, and a feeling of community. If you squint hard, perhaps you can see these two poles as rough stand-ins for the Republicans and Democrats of the 1980s. But DeLong doesn’t see Hayek and Polanyi as dialectical opposites — instead, he uses their frameworks to examine and evaluate all the other political-economic ideas that people came up with in the 20th century.

Thus, DeLong establishes a sort of rhythm for modern history. Hayekian free markets create growth, but people want more — they want their Polanyian social protections. So they create systems like communism, fascism, or liberal democracy, designed to temper the market’s natural inequality and bring about a better society. Sometimes these systems work out; often, they end in catastrophe and tears. At the end of the story, in 2010, liberal democracy more or less prevails, and people are fabulously rich by the standards of any previous age. But they’re still not satisfied; all this wealth and freedom has not made them feel like they’re living in a utopia. Perhaps all it would take is another vast leap in wealth to finally make human beings satisfied, but this may not be in the offing; productivity growth has slowed down, and it’s not clear if we’ll ever see anything like the 20th century again.

The book therefore ends on an ominous note — humans are still deeply unsatisfied with their society, and will doubtless try to create new big political-economic ideas as a result. If history is any guide, this path will be fraught with danger.

Slouching Toward Utopia is not a book that advances a central thesis; instead, it’s a book that encourages us to look at our recent past though a certain lens. DeLong narrates a set of events that most of us know well by now — European imperialism, the world wars, decolonization, globalization, the Great Recession, and so on. You will probably learn a few interesting historical tidbits from this book — DeLong has a frankly superhuman ability to remember and regurgitate endless fascinating little anecdotes and facts. But overall, the reason to read Slouching Toward Utopia is to re-frame your understanding of modern history — to see rapid economic growth as the unifying master narrative of the world since 1870.

I think that re-framing is a useful exercise. I’m no materialist, but I think it’s clear that changes in material circumstances create a new set of conditions that humankind has to adapt to. Of course it’s a two-way process — social organization can affect technological progress too. But technology is kind of magical in that it spreads very quickly around the globe. So as long as, say, refrigerators are invented somewhere, pretty soon people all around the world are going to want refrigerators. Sure, a single very important country can push progress forward — as happened with the U.S. in the 20th century. But overall, technology is global enough that its progress doesn’t depend too much on any one society’s choices about how to organize itself.

This, in a nutshell, is why I often call myself a “technological determinist”. Not because tech determines everything in society (it obviously doesn’t), but because it stands mostly above any one society, and it sets the constraints under which every society must operate. I see Slouching Toward Utopia as encouraging readers to see history through the lens of this sort of technological determinism.

DeLong’s vision of history is also a powerfully optimistic one. For many, it’s hard to look at the horrors of the 20th century — the concentration camps, the bombed-out cities, the despoiled landscapes — and not see a narrative of the Fall of Man. What use is technology, some ask, if it simply gives us better ways to murder each other and destroy our world? But to DeLong, all the 20th century’s monsters are merely maladaptive responses to a fundamental, underlying positive trend — the de-immiseration of the human race and the final conquest of the Malthusian demon (final because lower fertility rates will make the human race sustainable even if technological progress peters out).

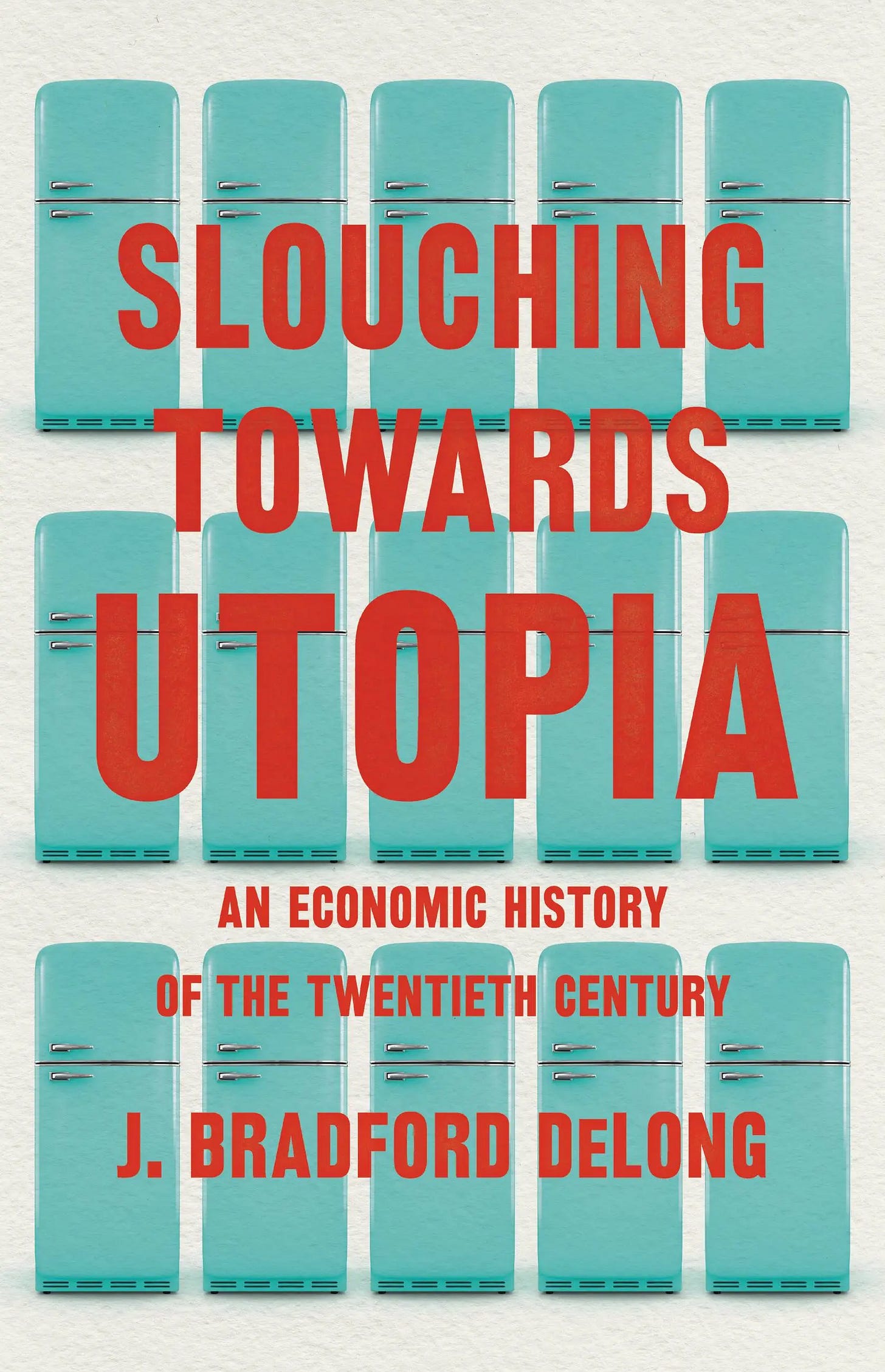

Yes, many people were slaughtered and brutalized during the 20th century. But a great many more were able to enjoy material standards of living of which their ancestors could only dream. In a nutshell, this happened:

No, this didn’t make Earth a paradise. But for most people, it made it no longer a hell. That’s not the end of humanity’s journey, but it’s a triumphant narrative nonetheless. Perhaps this progress is sustainable, perhaps not; we will certainly fight to make it so. But even if that fight ultimately fails, at least for a short time a whole lot of human beings got to live a life that wasn’t complete crap.

I call that a win.

In any case, I highly recommend Slouching Toward Utopia. The 20th century — even its “long” version — is now decisively over, and it’s a good occasion to reflect back and think about what it all meant.