NOTE TO SELF: "Coin Money, & Regulate the Value Thereof..."

TIME FOR A RANT: Today's Republicans is very weird; in this case, deeply weird about the Federal Reserve, & deeply, deeply confused about money & banking, & the Federal Reserve's constitutional...

TIME FOR A RANT: Today's Republicans is very weird; in this case, deeply weird about the Federal Reserve, & deeply, deeply confused about money & banking, & the Federal Reserve's constitutional basis...

Digging too deep into new weird arguments about “taxation without representation”, legal tender, the Congressional power to “coin money”, central banking, and the peculiar voting structure of the FOMC, with the context being a corrupt Supreme Court majority with no guardrails and no expertise.

TL;DR: The claim that the Fed is unconstitutional because Congress can no more delegate its power to “coin money” than it could delegate its power to declare war immediately fails on the grounds of logic and reason out of its historical stupidity.

The original intention & the clear public meaning of the Constitution text is that giving Congress the power to coin money gives it the power to direct the making of coins.

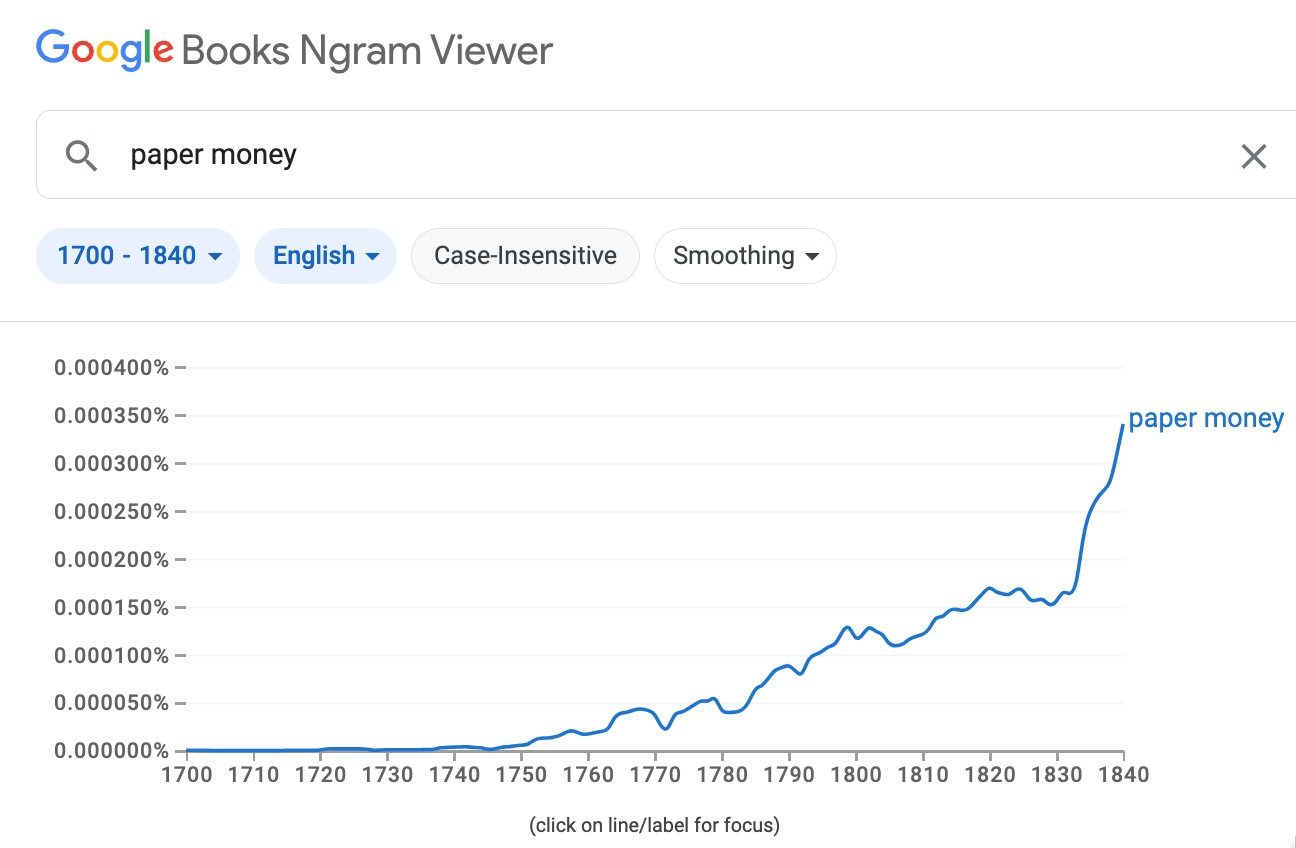

At the time of the Constitution, “paper money” was a new idea, to cover the case when “the circulating notes of banks and bankers… [because of] confidence in the fortune, probity and prudence… come to have the same [circulating] currency as gold and silver money”. Such bearer obligations of banks—effectively endorsed checks—were called “paper money” as a metaphor because they had come to act like money in the payments system, not because they really were money. They were just bearer obligations of banks, the kinds of things that arise in banking business. And they were in no sense “coined” by the government, as they were issued not by the governments but by banks doing banking

Federal Reserve Notes are bearer obligations of the twelve private government-chartered corporations that are the regional Federal Reserve Banks, not “money” in the eyes of the Constitution. The Congress has chosen to make them legal tender as part of its regulatory powers. Congress’s regulatory powers cover which banks are allowed and which are not allowed to issue such bearer obligations that can function like coins. And Congress has not delegated the power to decide what is and isn’t legal tender to anyone.

But there are no real originalists, believers in plain public meaning, or textualists on the Supreme Court, are there? The majority is composed of six tame and corrupt ideologues and Professional Republicans who could decide anything, isn’t it?…

One of the weirder things about the 2024 Michael Chea Harvard Kennedy School Macroeconomics Conference, & Larry Summers 70th Birthday Party was learning that there are Republicans who spend hours and hours debating “How can we stop the Federal Reserve from doing all the unconstitutional things it is doing?” And then learning that, in fact, there are so many of them that Dan Tarullo thinks it is time to prepare a road map to block them from using a tame and corrupt Supreme Court majority of ideologues and Professional Republicans eager to do the bidding of the party’s High Politicians to cause great chaös.

The unconstitutional things? It prints money. And it lets private bankers who are not officers of the United States—the twelve Presidents of the regional Federal Reserve Banks—perform key governmental functions. Since money is a full-faith-and-credit liability of the United States it implicitly levies future taxes. Because people who are not president-nominated and senate-confirmed vote on the FOMC, this violates the principal of no taxation without representation. And since there is an explicit constitutional requirement that it is Congress that has the power to “coin money”, the Federal Reserve cannot expand the money supply because printing money is not a power Congress can delegate.

This is all deeply confused.

The constitutional argument can be easily disposed of by noting that the Constitution gives Congress the power to “coin money”—to make coins. The Constitution is silent on paper money, which was back in the late 1700s, as Adam Smith said:

the circulating notes of banks and bankers… [when] the people of any particular country have such confidence in the fortune, probity and prudence of a particular banker… his promissory notes… come to have the same [circulating] currency as gold and silver money...

The Constitution is silent on banks’ issuing promissory notes—bearer bonds—and on people then taking such promissory notes and bearer bonds and exchanging them as means of payment. Indeed, back in the late 1700s the idea of “paper money” was still a new and semi-experimental thing. Calling bearer obligations of banks that played much the same role in the payments system as coins “paper money” was by analogy and a metaphor—these banker- and goldsmith-promissory notes are a lot like real coins, aren’t they”. Actual money was still coined precious metals.

The Federal Reserve System is a consortium of twelve government-chartered banks overseen by the Board of Governors, and Federal Reserve notes are the promissory notes of the consortium. Congress can and does regulate how or if banks can issue promissory notes that then circulate, and what the status of those notes are in contract settlement. But back in the late 1700s “coin money” did not mean “no bank can issue a promissory note or a bearer bond”. And that issuing of promissory Federal Reserve notes is what the Federal Reserve System does.

But there are now arguments about this. The first argument seems to be more-or-less this:

The US Constitution in Art. I, §8, ¶5 gives the US Congress the power “to coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures…”

This power cannot be—or the Supreme Court ought to decide that it cannot be—delegated to an independent agency. The Congress can no more delegate this power than it could set up an independent War-Decision Agency to decide when to declare war.

By printing money the Federal Reserve has seized this power. Moreover, because the notes the Federal Reserve prints are backed by the full faith and credit of the United States and that backing must be honored, the issuing of a Federal Reserve note is taxation without representation.

Any real textualist or originalist would say that the Federal Reserve is a collection of twelve government-chartered corporations, the regional banks, which have a convoluted governance and regulatory structure over them in the form of the seven president-nominated and senate-confirmed Governors who are the members of the Federal Reserve Board. The notes the Federal Reserve issues are not coined money, but rather are the Federal Reserve’s own obligations—its debts—created in a form which people find convenient to use as means of payment. Think of it as an endorsed check. This is people using the regional Federal Reserve banks to do banking—instead of writing a check on your own bank, you give them the equivalent of a check on the consortium that is the twelve government-chartered corporations that are the banks of the Federal Reserve system. Thus the printing of a Federal Reserve note has no connection with Art. I, §8, ¶5.

The rubber meets the road in the way the system operates with 31 USC ch. 51—Monetary System, which begins:

§5101: United States money is expressed in dollars, dimes or tenths, cents or hundreths, and mills or thousandths. A dime is a tenth of a dollar, a cent is a hundredth of a dollar, and a mill is a thousandth of a dollar.

§5102: The standard troy pound of the National Institute of Standards and Technology of the Department of Commerce shall be the standard used to ensure that the weight of United States coins conforms to specifications in section 5112 of this title.

§5103: United States coins and currency (including Federal reserve notes and circulating notes of Federal reserve banks and national banks) are legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues. Foreign gold or silver coins are not legal tender for debts.

“Legal tender” meaning that if you offer someone—tender them—Federal Reserve notes to pay the dollar value of a debt you owe, and your creditor refuses, the courts will then not help you collect it. “Legal tender” meaning that if you owe a tax or public charge, you can discharge the obligation by offering the government Federal Reserve notes. The printing of a Federal Reserve note thus does not unconstitutionally create a future tax obligation imposed on you, without your representation in the organization that imposed it. It, rather, provides you with a possible way to pay and discharge the taxes and public charges that congress has levied.

And if someone were to claim that Congress has unconstitutionally delegated its power to “coin money and regulate the value thereof” to the Federal Reserve, the answer is: nonsense. The Federal Reserve does its banking business. The Congress regulates the value thereof, and has chosen to do so by establishing 31 USC §5103. And Congress has the option to change this regulation by legislative enactment whenever and however it wishes—it has not delegated authority to change 31 USC ch. 51 to anybody.

But there are no real textualists or originalists on the Supreme Court, are there?

There are six justices who are Professional Republicans, and either highly corrupt or turning to blind eyes to corruption. Their primarily aim is to please whatever the High Councils of the Republican Party want to see happen. And as the High Councils shift, they follow, as far as they dare.

They might thus do anything.

The second argument is less stupid. It seems to be this:

The Federal Open-Market Committee—FOMC—is the policy-making legislation-established body within the Federal Reserve that decides on the level of interest rates the Federal Reserve System establishes in the economy via the system’s open-market operations.

The FOMC carries out core governmental monetary-policy functions.

The FOMC at any point in time consists of the seven president-nominated senate-confirmed Governors of the Federal Reserve as voting members, five of the regional Federal Reserve Bank Presidents as voting members, and the other seven regional Federal Reserve Bank Presidents as non-voting participants.

The regional Federal Reserve Bank Presidents—even though their appointments by the boards of the respective banks must be ratified by the Federal Reserve Board and even though the Federal Reserve Board can remove regional Federal Reserve Bank Presidents as long as it then communicates “the cause of such removal… to said bank” are not inferior officers of the United States.

Hence the FOMC’s decisions are unconstitutional because it has policy decisions being made by people who are not officers of the United States.

This argument has, I think, much more force.

Indeed: I was shocked when in September Trump-appointed Federal Reserve Governor dissented from the FOMC decision to reduce interest rates.

First, I was shocked because it was so highly unusual a thing. The convention is that Governors dissent only in extremis. And now is not in extremis. Regional Federal Reserve Bank Presidents can and do dissent—there have been 71 from the rotating five voting regional Federal Bank Presidents since 1993. But since 1993 there have been only six dissents from the Chair’s position at the FOMC meeting by any of the six other Fed Governors. The strong convention that Governors vote with the Chair exists to avoid the potential hit to the Fed’s legitimacy from the possibility that a Bank President who is legally a private banker casts a vote that determines what has become core government policy.

Moreover, there has been only one hawkish Governor dissent—until now.

Second, I was shocked by her rationale—that there were risks that inflation would rise because housing prices might be pushed up by illegal immigrants—which appeared and appears to me clearly mendacious, unprofessional, and a partisan political signal rather than a technocratic opinion on proper monetary policy.

So I would not think a change to the FOMC to make all twelve regional Federal Reserve Bank Presidents nonvoting participants in the meetings, leaving the seven Governors as the only voting members, would be a bad idea. A Supreme Court decision severing the clause making Federal Reserve Bank Presidents voting members and declaring it unconstitutional would seem to me to be a silly misreading, but not a bad thing.

On the other hand, without the FOMC how would things work? It is not the case that without the FOMC there would be no open-market operations. It is part of banking to adjust your asset portfolio. You do so by buying and selling securities on the open market. Before the FOMC existed, as regional Federal Reserve Banks bought and sold securities on the open market as they individually wished. They sometimes found themselves bidding against each other, and so neutralizing the effects of their actions. The FOMC was established as a coordinating mechanism, to get all of the banks on one page, following a consistent policy, with the FMC decisions, then directing the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to conduct all of the system’s open-market operations for itself, and for the other regional Banks.

From this perspective, the presence of the seven Governors on the FOMC is this a substantial expansion of the Board of Governors’ regulation of the 12 regional branches. The presence of the five voting Bank Presidents on the FOMC is not an intrusion into governmental functions of people who are not officers of the United States. Dissolving the FOMC as unconstitutional would in no way constrain the open-market banking operations that the twelve branches of the system would conduct, but just decoördinate them.

Thus a Supreme Court decision not severing the Bank-President voting-members clause and declaring the entire FOMC unconstitutional would lead to a system in which the twelve Bank Presidents would meet and coördinate by themselves. There would still be an FOMC-equivalent, but it would be an informal pickup committee—like, say, the executive-branch economic-forecasting troika—rather than a legislation-established body. And it would have zero instead of seven president-appointed senate-confirmed voting members.

But there are no real textualists or originalists on the Supreme Court, are there?

There are six justices who are Professional Republicans and either highly corrupt or turning to blind eyes to corruption. Their primarily aim is to please whatever the High Councils of the Republican Party want to see happen. And as the High Councils shift, they follow, as far as they dare.

They might thus do anything.

Reference:

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2024. "We Have Trump Fed Governor Appointee." Grasping Reality. September 18. <https://braddelong.substack.com/p/we-have-trump-fed-governor-appointee>.

Smith, Adam. 1776. An Inquiry into the Nature & Causes of the Wealth of Nations. London: W. Strahan & T. Cadell. <https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/3300/pg3300-images.html>.

Tarullo, Daniel K. 2024. "The Federal Reserve & the Constitution." Southern California Law Review. 97:1 (May 14), pp. 1–50. <https://southerncalifornialawreview.com/2024/05/14/the-federal-reserve-and-the-constitution/>.

The same people who will, when you complain about our lack of one-person, one-vote institutions, lecture you on checks and balances and separation of powers now want to have Congress do what the Fed does. Because they won an election by 2%, and fear one-person, one-vote.

On rant: you're basically right but practicing law without a license can be dangerous. A few points:

1. Opinions differed--even back in the 1780's--whether paper money was or wasn't real money. There was a nice symposium on the nature of money, published in "The American Museum" in 1787. A distinction was drawn between state notes issued against future tax payments, and mercantile notes issued by banks.

2. Banks, as corporations, were viewed as parastatal enterprises in those days. (Some US banks did not incorporate, but they generally sought charters when they could get one.) The delegation problem was a hot-button political issue at the time. Debates & Proceedings of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania, On the Memorial Praying a Repeal or Suspension of the Law Annulling the Charter of the Bank (Matthew Carey, ed., Philadelphia, Seddon & Pritchard 1786). There was no doubt that they were money equivalents. Miller v. Race, 1 Burr. 452, 97 Eng. Rep. 398, 401 (K.B. 1758) (Mansfield, L.J.)

3. None of this makes a damn bit of difference, because Federal Reserve notes are issued by the federal government and guaranteed by Reserve Banks. See Sections 16(1) and 16(2) of the Federal Reserve Act. The obligation is not delegated. Never trust the Federal Reserve on the source of its powers.

4. Congress indeed has a near-monopoly on defining legal tender. (There's the gold and silver exception for the states--which means, in practical effect, that a wingnut state can abolish the sales tax for gold and silver and say it is doing something of Constitutional moment.) But legal tender doesn't mean diddly-squat. It's just a default rule of contract law, which prevents sharpsters from refusing payment because they benefit more from breach of contract. Simmons v. Swan, 275 U.S. 113 (1927). Normies don't care about legal tender, as long as what they get is safe, convenient, and liquid. Indeed, Federal Reserve and National Bank notes were not legal tender before about 1935. In the days of gold, anybody could transact around legal tender by demanding gold or gold's worth. A declaration of legal tender was a sign of monetary weakness, not strength. Charles Goodhart, The Evolution of Central Banks 20 (MIT 1988).

It was the abrogation of the gold clause that killed the gold standard, not legal tender. These days, nobody cares about legal tender. If you look at UCC Article 4A-406(b), you'll see that state law has created a legal tender of its own. This is the law governing wire transfers, and thus trillions of dollars every day. (It's been partially federalized.)