FIRST: Paul Krugman Reviews My “Slouching Towards Utopia”

Book forthcoming September 6!: <bit.ly/3pP3Krk>. This was very, very nice to see:

Paul Krugman: Technology & the Triumph of Pessimism: ‘“Slouching Towards Utopia,” by Brad DeLong… a magisterial history of what DeLong calls the “long 20th century,” running from 1870 to 2010, an era that he says… was shaped overwhelmingly by the economic consequences of technological progress…. For the great bulk of human history… Malthus was right: There were many technological innovations over the course of the millenniums, but the benefits of these innovations were always swallowed up by population growth, driving living standards for most people back down to the edge of subsistence…. Around 1870, however, the world entered an era of sustained rapid technological development that was unlike anything that had happened before; each successive generation found itself living in a new world, utterly transformed from the world into which its parents had been born….

There are two great puzzles….

The first is why this happened. DeLong argues that there were three great “meta-innovations” (my term, not his)—innovations that enabled innovation itself. These were the rise of large corporations, the invention of the industrial research lab and globalization….

The second is why all this technological progress hasn’t made society better than it has. One thing I hadn’t fully realized until reading “Slouching Towards Utopia” is the extent to which progress hasn’t brought felicity. Over the 140 years DeLong surveys, there have been only two eras during which the Western world felt generally optimistic about the way things were going…. The first… was the 40 or so years leading up to 1914, when people began to realize just how much progress was being made and started to take it for granted…. The second… was the “30 glorious years”… after World War II when social democracy… seemed to be producing not Utopia, but the most decent societies humanity had ever known. But that era, too, came to an end, partly in the face of economic setbacks, but even more so in the face of ever more bitter politics….

The progress that brought us on-demand streaming music hasn’t made us satisfied or optimistic. DeLong offers some explanations for this disconnect, which I find interesting but not wholly persuasive. But his book definitely asks the right questions and teaches us a lot of crucial history along the way…

Of course, the industrial research lab, full globalization, and the modern corporation were not the only things going on as far as generators of global technological progress—discovery, development, deployment, and diffusion—were concerned. But everything before had only pushed worldwide technological progress up to a proportional rate of 0.45%/year, on the edge of but not quite to disspell the Devil of Malthus. And as of 1870 it was not at all clear that that rate of technological progress could be sustained. There had been “efflorescences” before, but they had not lasted. Was there as of 1870 yet sufficient reason to imagine that the Industrial Revolution was more than just another such “efflorescence”, and that London would escape the fate of Nineveh, or Tyre?

It is after 1870 that the worldwide average rate of technological progress explodes: what Simon Kuznets first named “Modern Economic Growth” Growth jumped up from the 0.45%/year average proportional rate of 1770-1870 to the 2.1%/year average of 1870-2010. A full revolution in the global mode of production—a doubling of humanity’s technological competence—took 150 years at the pace of 1770-1870. It took only 33 years after 1870.

If one wanted to say that each quantitative doubling of human technological capability, measured in the sense of being able to support the same population at twice as high a living standard, is an equal qualitative change in the underlying mode of production, then starting from the standpoint of the 2035 built-out Information Age and looking backward in time, I see ten different “modes of the forces of production” since the dawn of agriculture:

Modes of the Forces Production in History

2035: Information Age

2002: Global Value-Chain Age

1969: Mass Consumption Age

1936: Mass Production Age

1903: Industrial Age

1870: Steam-Power Age

1605: Imperial-Commercial Age

1: Late Agrarian Age (feudal, ancient, asiatic)

-1300: Bronze Age

-4900: Neolithic Age

-13000: Mesolithic Age

If one follows this line of thought, then out of our ten “modes of production” in the past ten-thousand years, fully six have been in the past 200. If one thinks that on top of the forces there have to be built institutions that are the relations of production, and that on top of the forces-relations base one has to build the institutions that are the superstructures of society, then it is quite clear why not just utopia but even stable patterns of social order have been so hard to build in the Modern Economic Growth Age that began in 1870: processes of institutional evolution and adjustment that we used to have hundreds or thousands of years to get right and file the rough edges off now take mere decades.

And I have written back:

Brad DeLong: Thank you very much. Blush. I hope that people incentivized to buy the book via your praise are not disappointed… <https://t.co/2mdNZlwhUE>

Tell me: You write:

The progress that brought us on-demand streaming music hasn’t made us satisfied or optimistic. DeLong offers some explanations for this disconnect, which I find interesting but not wholly persuasive. But his book definitely asks the right questions and teaches us a lot of crucial history along the way.

As I see it, the two big questions I don’t deal with satisfactorily are

Why we have done so much better to spread biomedical in public health technology around the world to increase life expectancy then spreading the technologies of high productivity around the world.

Why was humanity so great during the Long 20th Century at:

baking a bigger (much bigger! hugely bigger!! so big that now there are no barriers in terms of productivity for everyone to have what every previous civilization would have seen as enough) economic pie, while continuing to be so completely inept at both

equitably slicing the pie, and

tasting—enjoying—the economic pie.

What do you say the answers to those two questions are? And what else do you think I have gotten BigTime wrong in the book?…

LINK:

One Audio:

Michael Patrick Cullinane & Patrick O. Cohrs: The New Atlantic Order <https://shows.acast.com/gildedageandprogressiveera/episodes/new-atlantic-order>

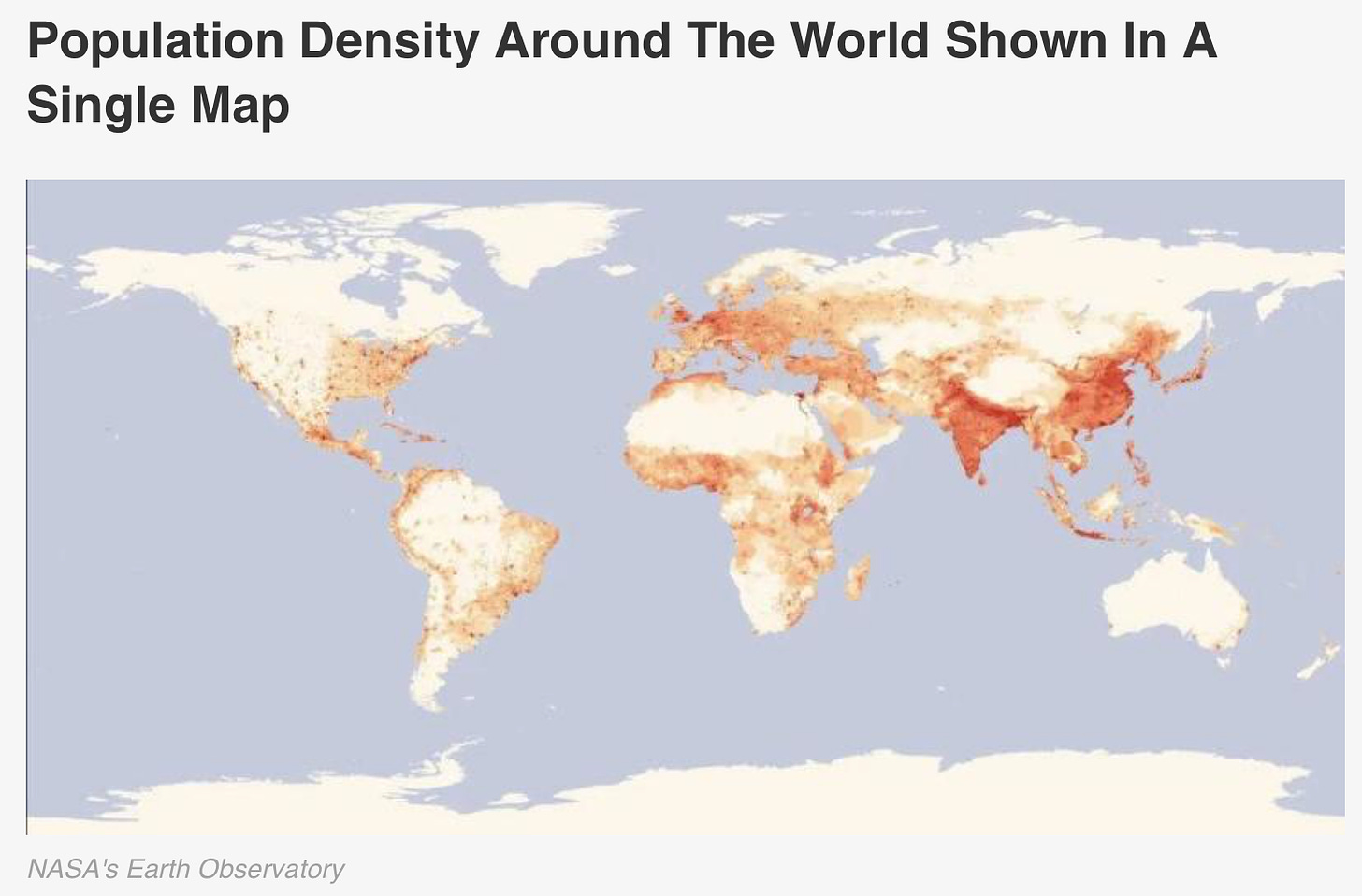

One Image:

Very Briefly Noted:

Charlie Warzel: The “Hollow Abstraction” of Web3: ‘I cannot stop watching videos of Web3 boosters failing to explain the usefulness of the technology. I realize this is petty, but the videos are deeply cathartic…. It’s baffling how befuddled these men look when asked to articulate concrete, compelling use cases for their next big thing… <https://newsletters.theatlantic.com/galaxy-brain/62ba500cbcbd490021aaef70/web3-crypto-movement-uses-marc-andreessen/>

Chen Yeh & al.: Monopsony in the US Labor Market: ‘Manufacturing plant… an average markdown of 1.53…. The aggregate markdown… decreased between the late 1970s and the early 2000s, but has been sharply increasing since… <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20200025>

Olga Kharif: Cryptocurrency Bear Market: This Bitcoin Crash Is Different From the Past: ‘Crypto collateral that seemed valuable enough to support loans one day became deeply discounted or illiquid, putting the fates of a previously invincible hedge fund and several high-profile lenders in doubt… <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-26/crypto-winter-why-this-bitcoin-bear-market-is-different-from-the-past#xj4y7vzkg>

Marc Goñi: Assortative Matching at the Top of the Distribution: Evidence from the World’s Most Exclusive Marriage Market: ‘When Queen Victoria went into mourning for her husband, the Season was interrupted (1861–1863), raising search costs and reducing market segregation… <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/app.20180463>

Ben Thompson: Web3 Use Cases: ‘The fundamental concept of a neutral arbiter that… adds a thin layer of authentication on top of existing, scaled services that invest heavily in the user experience, is extremely interesting, to me anyways…. [But] I can’t say I’m particularly broken up about either the ongoing crypto crash or the backlash to Web3: there is a ton of cruft that needs to get swept away and crap that needs to be refuted before actually useful stuff can be built… <https://stratechery.com/2022/passport-update-independence-and-interoperability-web3-use-cases/>

Cory Doctorow: Decrapify Cookie Consent Dialogs with the Consent-O-Matic: ‘Today, I added…. GDPR consent dialogs remain a hot mess, which is where Consent-O-Matic comes in… <https://pluralistic.net/2022/06/28/bartlebytron-3000/#i-would-prefer-not-to>

Twitter & ‘Stack:

Paul Krugman: ‘Not, it turns out, the optimal day to write about long-run economic growth. Still, you should buy Brad DeLong’s deeply enlightening book…

Branko Milanovic: ‘Marx was the first student of capitalism, Keynes, the last cameralist…. In Capital, we have a Bible_ of capitalism, in General Theory, we have The Prince for economic management…

¶s:

This industrialization-education-language-nationalism cycle as one of the keys to much of post-1800 history: Ernest Gellner was very wise indeed:

Cosma Shalizi: Ernest Gellner, Nations & Nationalism: ‘The inhabitants of… “Agraria” were economically static and internally culturally diverse…. Because industrial economies continually make and put into practice technical and organizational innovations… their occupational structures change significantly in a generation…. No one can expect to follow in the family profession…. Training must be much more explicit, be couched in a far more universal idiom, and emphasize understanding and manipulating nearly context-free symbols…. It must in short take on the characteristics formerly associated with the literate High Cultures of Agraria…. States become the protectors of High Cultures, of “idioms”; nationalism is the demand that each state succor and contain one and only one nation, one idiom…. Faced with a difference between one’s own idiom and that needed for success, people either acquire the latter, or see that their children do (assimilation); force their own idiom into prominence (successful nationalism); or fester. Thus industrialism begets nationalism, and nationalism begets nations…. It is hard to decide whether nationalists or anti-nationalists will find Nations and Nationalism more disturbing; rootless cosmopolitan though I am, it changed my mind on a great many subjects. This is already a rare enough achievement for a philosopher or social scientist…. Unfortunately for those of us not enamoured of nationalism, he wasn’t talking rubbish at all…

A successful aggregator-monopolist does not manage to extract all of the consumer surplus for itself—the fact that you could spend your money on other things that are imperfect substitutes limits surplus extraction to about half. Unfortunately, another quarter of the consumer surplus vanishes to deadweight loss: monopoly is not a good market structure.

And, on the producer-surplus side, Amazon’s shift from being an intermediary that aggregates consumer information to guide users’ attention to where it is likely to be best-satisfied to one that makes producers pay through the nose for that attention—that means that Amazon is likely to grab a huge proportion of producer surplus as well.

Thus I very, very much hope Web3 will come to our rescue, somehow, soon:

Adrian Hon: The Forever War: ‘Review of Book Wars: The Digital Revolution in Publishing by John Thompson…. Thompson… interviewing over 180 senior executives and staff in the publishing industry…. Depending on whether you include KDP in your analysis of the book market as a whole, traditional publishers are either doing just fine or are being utterly dominated by Amazon. The problem is that the exact size and contours of KDP can only be determined through guesswork and inference….

The latest version of disintermediation to hit the publishing industry, Substack, isn’t covered in the book…. Substack is notable because it has cracked the seemingly impossible problem of getting readers to pay for non-fiction words on a screen—to the tune of $5–10 a month each, which amounts to roughly £45–75 a year. Email newsletters certainly aren’t a get-rich-quick scheme, but it’s working well for a lot of authors…. As for authors, the new possibilities offered by self-publishing, crowdfunding and newsletters may seem daunting, but they only exist because there are countless people ready to pay good money for good writing. The future will always have a place for authors…

Social engineering would, I always thought, mean that the panopticon would win in the struggle of anonymity vs. panopticon. I would not bet that the FBI, the NSA, and company have not already nailed who the original BitCoin 64 are, and are not working their way down the tree:

Physics ArXiv Blog: Why Bitcoin’s Anonymity Could Soon Collapse Like A House of Cards: ‘The distribution of Bitcoin very quickly follows… the Pareto distribution…. Since it achieved $1 parity, almost everyone using Bitcoin can be traced to one of the 64 founding accounts in less than six steps. So if the identities of first 64 agents are known, almost anyone else can be de-anonymized in just six steps or fewer. In this way, the anonymity of the entire network could fall like dominoes. That’s interesting work that will make uncomfortable reading for more than a few individuals in the Bitcoin universe…

Put me down as someone who thinks that consumers should wish for Web3, even though they do not know it yet:

Max Chafkin: Web3 Is the Big Idea Customers Didn’t Ask For: ‘Seventeen years ago, Paul Graham… argued… entrepreneurs should be skeptical of venture capitalists, that they should be obsessively cheap, and that they should focus on small, unsexy markets. Above all, Graham urged founders to seek out customers from the very beginning and to respond to their needs. “Make something customers actually want,” he said. Over the next two decades, this advice became canonical in Silicon Valley. Graham co-founded an incubator and venture capital firm, Y Combinator…. The advice was applied to an entire generation of so-called Web 2.0 companies—a cat…

I have been reading your previews of the book (already ordered months ago) as they appear.

Relating to your identification of 1870 as the takeoff point, something that has always struck me is that you can look at almost any industry in that period and be astonished by how quickly various final products went from small and simple to gigantic and complex, across many different final products. From USS Monitor to USS Arizona in less than fifty years, from the V-2 to the Saturn V in about twenty years, from the Wright Brothers to the B-29 in less than forty years.

I am not sure of what all the drivers of that kind of gigantism were--bigger bomber, bigger bombload, of course--but innovations in management and manufacturing processes--one of your meta-innovations--must have been essential, maybe even more than technological innovation. You need to be much better organized, and on a massive scale, when you are building B-29s than when you are building a Wright Flyer.

The wayback link to Shalizi's Gellner post didn't work for me, but he still has it up on his own site: http://bactra.org/reviews/nations-and-nationalism/