Paul Krugman: Twitter Review/Critique of “Slouching Towards Utopia”, & Response

Yet another Twitter review...

Paul Krugman: Twitter Thread: ‘As they say in the Patrick O'Brian novels, I give you joy of your victory!

I am extremely gratified to find myself at #6 on the NYT nonfiction bestsellers after launch week! And today is the UK launch for “Slouching Towards Utopia”: <fal.cn/3rUOr>. (In US: <bit.ly/3pP3Krk> I am almost as gratified that Martin Wolf likes it. So… 1/

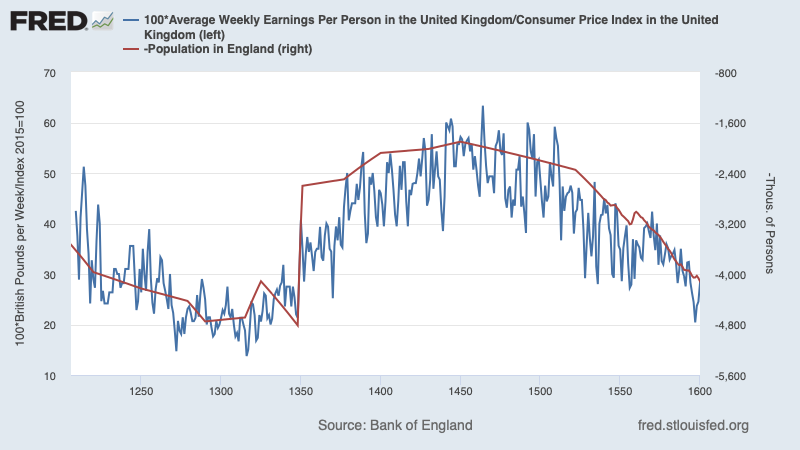

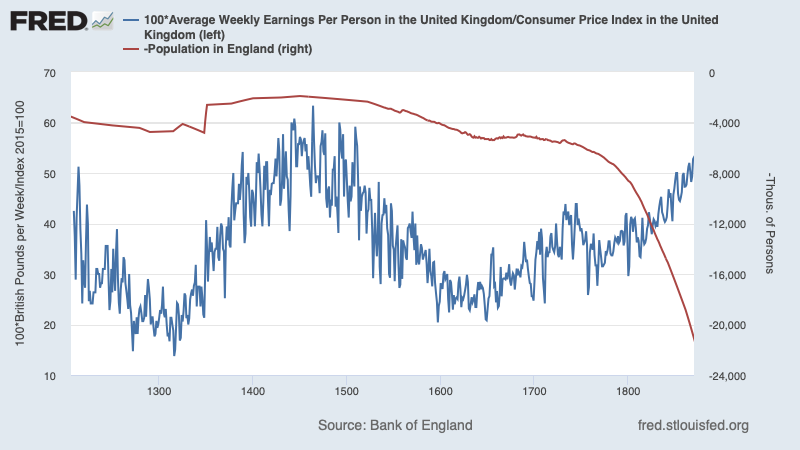

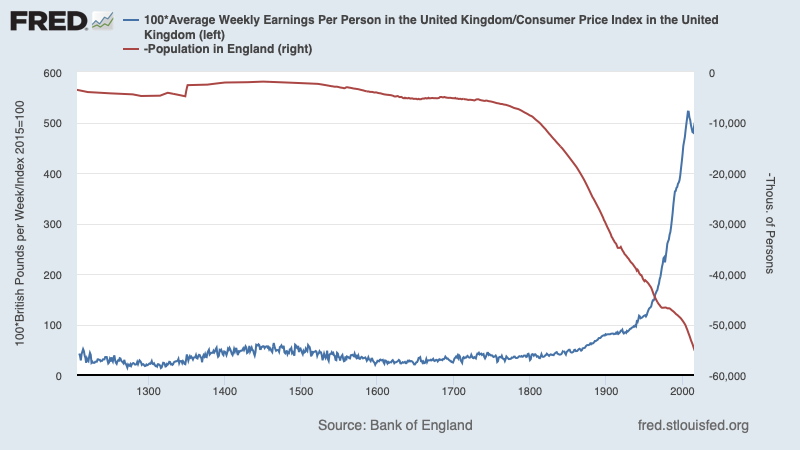

A few FRED-based thoughts on one of Brad's big insights: that the world didn't really break out of the Malthusian trap until 1870. As it happens, my friend FRED includes the Bank of England dataset with estimates of some UK variables going back to the Middle Ages. And it allows me to make a few pictures of real wages versus population.

Up through 1600 the world was Malthusian pure and simple. Real wage in 2015 pounds versus population (inverted): just sliding up and down the curve with the rise and fall of plagues:

Fast forward to 1870, and real wages were no higher than they had been in the 15th century—but the population was much larger, so evidence of technological progress:

Only after 1870 do we see a huge improvement in working-class living standards:

The question is how we should think about the century or so before 1870 when real wages were rising moderately despite a growing population. Brad argues that the pace of technological progress was still glacial by modern standards. And there had been previous eras of significant economic growth — the Dutch Republic? The early Roman Empire?—that never achieved escape velocity. So maybe the real break didn't come until 1870. By the numbers, this looks right.

But maybe the economic numbers don't tell the whole story? It seems to me that between 1600 and 1870 there was a revolution in how people thought—a rise in systematic thinkers from Newton to Darwin, including, yes, Malthus himself—that had no previous counterpart. Not just scientists, either. I'm kind of a Civil War buff, and it has always seemed to be that people like Grant and Lincoln were modern in a way you couldn't find in earlier eras. For that matter, did the ancient world have an Alexander Hamilton?

I guess my point is that I suspect that the intellectual and maybe social foundations for the big break were laid well before the big uptick in total factor productivity.

This isn't a critique of Brad's work: It's an important and novel observation that the trends didn't really break until circa 1870. And maybe it's just hindsight that makes the squishier changes seem so important. But maybe not.

To which I replied: Suppose that you are willing to accept my heroic assumption that “technology” is proportional to average real income per capita times the square-root of population, and suppose that you are willing to accept our guesses about past population and my hard-Malthusian view of 1500 and before...

Then you do indeed get an Axial Age -1000 to 150 technology proportional growth rate of 6% per century; a Late-Antiquity Pause 150 to 800 growth rate of 1.4% per century; and then a Mediæval 800 to 1500 growth rate of 5% per century:

And it is pretty clear why. The aims of the élites who direct humanity’s energies are devoted to maintaining the force-and-fraud exploitation-extraction-&-domination machine that they—the thugs-with-spears, their bosses, and their tame accountants, bureaucrats, and propagandists—run on the rest of humanity as the only way that élite members can have enough for themselves and their families. Ideas are judged primarily not by whether they are true or productive but by whether they reinforce the force-and-fraud machine. There is progress—coinage in -600, after which you can construct a division-of-labor with more than your friends, neighbors, and relatives without having to go through the kings and priests—the moldboard plow, double-cropping rice, the merino sheep, and so forth. But it is slow as social energies are directed elsewhere.

And the 150 to 800 Late Antiquity Pause should make you doubt whether there was any arc of history making for an increasing technology growth rate.

Then with 1500 comes the Imperial-Commercial Revolution Age, and the rate of technology growth triples to 15% per century. As I see it:

1/3 of this is simply Mediæval (but now Gunpowder-Empire) business as usual,

1/3 of this is the Columbian Exchange and such, and

1/3 of this is a historically unique tinkering-inventing-recombining culture (Patrick Wyman’s book “The Verge” is, I think, very good on this) at the western edge of Eurasia.

Is this a sea-change in thought and society? Maybe. But the builder of the Antikythera Device, the inventor of coinage, and that guy Ish-baal who thought up the idea of using a stylized picture of an ox to stand for a particular phoneme way back in the year -1000 might say you nay.

Then from 1770-1870 we get the Industrial Revolution Century: an additional tripling of the technology growth rate worldwide from 0.15% to 0.44% per century. Again I divide this into thirds:

1/3 from the globalization benefits of concentrating the entire manufacturing of the globe in the region most productive,

1/3 the very lucky fact that the last glaciers scraping off the post-Permian rock had given us access to mines of unbelievably cheap and accessible coal—stored sunlight of an unbelievable concentration and ease of use once you had unlocked its secret—and

1/3 to a unique engineering-inventing culture in the 300-mile radius circle around Dover, England (plus offshoots).

The first two of these three tranches seem to me to have been overwhelmingly likely to have been transient.

And so, had technological progress continued after 1870 at 1/3 of the 1770-1870 rate—at 0.15%/year—humanity would still have been under the Malthusian harrow, with typical living standards constant at the rate that supported population growth of 0.3%/year—8% per generation—and no demographic transition.

Call this Permanent Steampunk World.

2010 would then see the technologies of 1890 or so, but with a much larger and hence much poorer human population than in actual 1890.

Would that world have been “modern”?

It would have had its Marx and its Freud. It would know relativity and quantum mechanics. But we are talking a typical world standard of living of $4 a day—not quite World Bank “dire poverty”, but damned close.

But this no-Industrial Research Lab to rationalize and routinize discovery and development, and no Modern Corporations to rationalize and routinize development and deployment of the Second Industrial Revolution technologies—does this make sense?

Quite possibly not. Nate Rosenberg and David Mowery would say you could not have the market economy of 1850 and the engineering profession and machine tool industry as they then stood and not go on to develop the IRL and the MC. And then the economy of 1850 was immanent in the society created by the early steam engine. And so on back to 1070 and the Investiture Crisis, which establishes the principle that law is more than the servant of the powerful but binds even the most powerful. And possibly back before 1070 as well: you can find anticipations of the shift from gemeinschaft to Gesellschaft, rational inquiry into the operation of the world, and so on however far back you look, if you try hard enough.