Print the Perpetual (Consol) Bond

The "debt ceiling" problem is not a real problem constraining Treasury operations; it is only if the Biden administration pretends that it is a constraint and hence a problem that it becomes one.

I confess I never understood why the debt ceiling became a thing in the first place. Congress passes laws on taxes. Congress passes laws on spending. Congress passes laws on taxes. Congress passes laws on the debt ceiling. And if these are inconsistent? When laws are inconsistent you construe that latest in time as constructively repealing the earlier in time, taking into account the background assumptions about how government normally operates—i.e., no technical tricks to make the dodge that what seems to be inconsistency is not really inconsistency at all.

But Jimmy Carter’s Justice Department said “no”. Jimmy Carter’s Justice Department said, rather, that government spending can only proceed if all ducks are in a row: (a) congress has to authorize the spending, (b) congress has to appropriate the spending, and (c) congress has to raise the debt limit so that the Treasury can sell bonds. If not (c)? Well, then, the spending cannot take place. So the Carter Justice Department said. Why it said this, and why everyone else went along with it, is something that nobody has ever been able to explain to me.

Josh Marshall says: coin, Fourteenth Amendment, consol bonds with a face value equal to a single one of their six-month coupons, or Thunderdome. Paul Krugman says: coin or consol. I am still on team: Just say Jimmy Carter’s Justice Department was mushugannah, and deem the debt ceiling limit constructively repealed.

But if you want a technical trick dodge, this one seems to be best: 31 U.S.C. §3101:

Public debt limit

(a) In this section, the current redemption value of an obligation issued on a discount basis and redeemable before maturity at the option of its holder is deemed to be the face amount of the obligation.

(b) The face amount of obligations issued under this chapter and the face amount of obligations whose principal and interest are guaranteed by the United States Government (except guaranteed obligations held by the Secretary of the Treasury) may not be more than $31,380,000,000,000, outstanding at one time, subject to changes periodically made in that amount as provided by law through the congressional budget process described in Rule XLIX of the Rules of the House of Representatives or as provided by section 3101A or otherwise.

(c) For purposes of this section, the face amount, for any month, of any obligation issued on a discount basis that is not redeemable before maturity at the option of the holder of the obligation is an amount equal to the sum of—

(1) the original issue price of the obligation, plus

(2) the portion of the discount on the obligation attributable to periods before the beginning of such month (as determined under the principles of section 1272 (a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 without regard to any exceptions contained in paragraph (2) of such section).

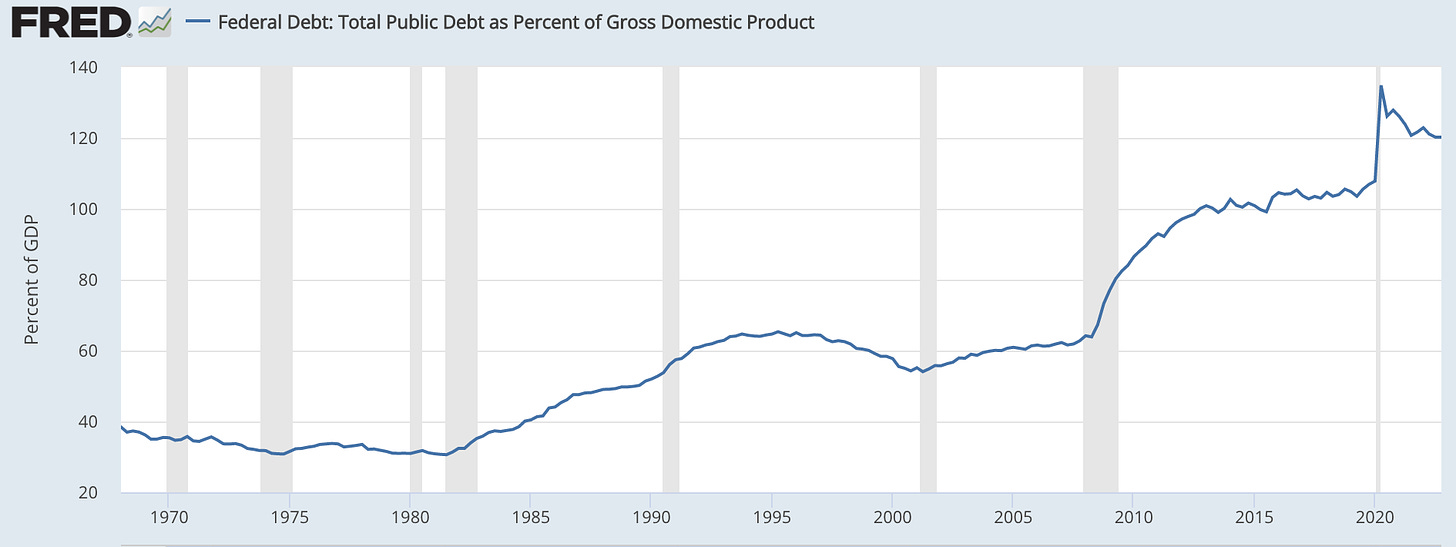

Under USC §3101(a), a consol redeemable at the holder’s option for its next six-month coupon has a face value equal to one six-month coupon, and is so counted in the calculation of outstanding debt subject to limit. Problem solved. And the only reason for the Yellen Treasury not to take that road and issue the consol is if White House political affairs thinks there is some indirect advantage to the country from pretending this is a real problem, which the president is trying to solve via good-faith bipartisan negotiation.

If there is some indirect advantage from actually spending time and energy on this, I would very much like someone to tell me what it is.

Congress created the debt limit during WWI (1917), as a way to make it *easier* to borrow money!

Article 1, Section 8, of the Constitution gives the exclusive power to borrow money to Congress -- not to the Executive. So, prior to the debt limit's creation, Congress was required to explicitly approve each and every individual bond offering or other borrowing. But, with the growth of the federal budget, the increased pace of borrowing, and the growing variety of borrowing methods, it became increasingly cumbersome for Congress to be so closely involved in the details of the borrowing process. So, Congress passed the debt limit as a way to authorize Treasury to borrow what it needed -- up to a limit -- without requiring additional Congressional action. (For some history see this 1954 article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2976566) (Also, imagine if the "do-nothing" Congress we have today needed to individually authorize each borrowing by the government!)

The debt limit was raised, without controversy or resistance, even during the Depression and WWII, until 1953 when Conservative Democrat Harry Byrd, of Virginia, led an effort to successfully deny President Eisenhower's request for an increased debit limit. Without that increase, Eisenhower was forced to cut expenditures and Treasury, for the first time, employed a variety of "extraordinary measures" to avoid new borrowing. Thus, fiscal conservatives learned that the debt limit could be used not only to make borrowing and spending easier, but also to reduce it. Ever since 1953, the debt limit has been seen as a way to limit borrowing, and thus expenditures, whereas before 1953, it was more often seen as a means to enable borrowing to fund expenditures.

It is important to point out a major difference between 1953 and today. When Byrd and others fought to deny a debt limit increase, they never imagined that there was any real prospect that the government might not be able to cover its obligations. They assumed, correctly, that the President could and would ensure that the full faith and credit of the USA would be preserved by cutting spending, etc. They wouldn't have denied the increase if they actually believed that there was a realistic chance of long-term damage. Unfortunately, we have many people in Congress today who seem much more comfortable with the idea of debt default. They are fools.

There is a principle of statutory interpretation called "avoidance of constitutional doubt." If Interpretation A of a statute raises no constitutional issues, and Interpretation B raises an open constitutional issue, courts go with Interpretation A, if Interpretation A is in the ballpark. It's a nifty way of invoking the 14th Amendment without actually invoking the 14th Amendment.

If it ever gets to the Supreme Court from a judge like Kacsmarek or Cannon, they'll probably consider the entire question nonjusticiable. That's a lawyer word for "too political for us to handle." But the constitutional doubt approach may be the most politically legitimate, even if it never gets to the lower courts.