Discover more from Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality

PROJECT SYNDICATE: America's Macroeconomic Outlook

In which I set myself up on the hill as the last member of "Team Transitory"...

America's Macroeconomic Outlook

Mar 25, 2022

Given the depth of the recession caused by COVID-19 in early 2020, the current state of the US economy and labor market is nothing short of spectacular. And though an inevitable increase in inflation has rained on the parade, there is still good reason to think that it will subside in the medium term.

BERKELEY – Many who now worry about rising inflation in the United States may disagree, but the US Federal Reserve should take a victory lap. Just consider what the Fed has achieved over the past two years.

At this time in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had pushed employment down by a massive 14% when large portions of the economy were forced to shut down. And although employment bounced back when the economy began to reopen, it nonetheless remained 7% below its pre-pandemic level.

Getting back that remaining 7% was always going to be difficult, because it required a re-division of labor. During the disappointing, anemic, unsatisfactory recovery from the Great Recession a decade ago, re-knitting the fabric of the labor market occurred at a pace that increased employment only about 1.3 percentage points per year. Because demand was slack and growing only very slowly during this period, it was difficult to figure out which business models would be profitable and where labor was really needed.

This time, the re-knitting happened much faster. Employment rose by 5% in the space of just a year, because the Fed and US President Joe Biden’s administration did not take their feet off the accelerator too soon, as their predecessors had done in the early 2010s. They should regard today’s economy as a massive policy victory – perhaps the greatest that I have seen in the US. Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues should be very proud.

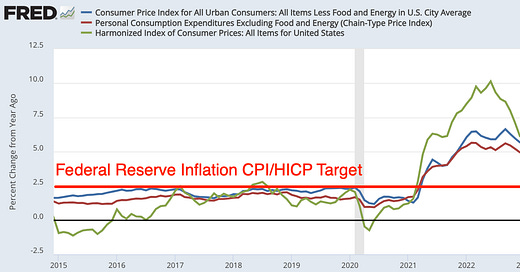

Higher inflation, as a side effect and a consequence of the robust recovery, was inevitable and therefore not regrettable. When you rapidly rejoin highway traffic at full speed, you are going to leave some rubber on the road. The question now is what will happen next. The bond market seems to think that this wave of inflation will pass, with price stability returning in the medium term. The market currently anticipatesthat in 5-10 years, inflation will average 2.2% per year.

There is always a chance that the market is wrong. But in this case, I trust its judgment. The bond market can be trusted not because it is a good forecaster (it is not), but because of what it tells us about expectations. If current US inflation does not fade away quickly, that will be because people did not expect it to do so. Fortunately, as Joseph E. Gagnon of the Peterson Institute for International Economics points out, the people whose expectations matter here are largely the same people placing bets on the bond market.

Taking a broader historical view, there were six episodes of US inflation above 5% in the twentieth century. One came during World War I, but this inflation turned into substantial deflation and a deep, short recession, owing to what Milton Friedman later determined to have been an excessive increase in interest rates (from 3.75% to 7%) by the Fed.

Another episode was during World War II, when inflation was tamped down with price controls. The next two were after WWII and after the Korean War, when inflation proved transitory and passed quickly without substantial monetary tightening. And the last two came to define the 1970s, with the final episode ultimately being scotched by a deep recession following Fed Chair Paul Volcker’s massive interest-rate hikes.

Whether they realize it or not, everybody making arguments about the likely course of today’s inflation is arguing not from theoretical principles but from arbitrary historical analogies. Some, like my sharp former teacher, Olivier Blanchard, see the 1970s as the best analogy. But while that may prove to be correct, they have a weak case. The 1974 outbreak of inflation came after a previous inflationary bout that had shifted expectations. By 1973, people had come to expect that the inflation rate, in the absence of a recession, would remain around where it had been the previous year – if not a little higher. By contrast, I see zero evidence today to suggest that US inflation expectations have become unanchored.

Moreover, US employment is still some 7.3 million below its pre-pandemic trend. In a recent paper, Lawrence H. Summers (another sharp former teacher) and Alex Domash attribute a 2.7 million shortfall to structural factors such as population aging and immigration restrictions. But that still leaves 4.6 million people who have left the labor force but could be tempted back by a sufficiently strong economy. This potential labor pool reduces my fear of an inflationary wage spiral, which happens when employers try to hire more workers than can be made available.

In addition to a wage-price spiral, the other two commonly named culprits for non-transitory inflation are supply-chain bottlenecks and self-fulfilling expectations. Among these three, the only potentially serious risk is that we may not be able to resolve key supply-chain disruptions.

That brings us to the bad news. Supply-chain risks may have grown more acute now that Russia’s war against Ukraine has sent oil and grain prices spiraling upward, as happened in the early 1970s. Thanks to Russian President Vladimir Putin, the 1970s could turn out to be the right analogy after all.