READING: David Abernethy (2000): Þe Dynamics of Global Dominance: European Overseas Empires 1415–1980

The European edge in the Imperial-Commercial Age 1500-1770: Priests, merchants, soldiers, sailors, & shipwrights all working together under a king for gold, glory, & God...

David Abernethy (2000): The Dynamics of Global Dominance: European Overseas Empires 1415–1980: ‘Beijing… was the capital city of a powerful state lacking both an expansionist foreign policy and an expansionist religion. Mecca was the central city of an expansionist religion but not of a state. Lisbon was the capital city of a state with an expansionist foreign policy and a strong commitment to spread an expansionist religion.

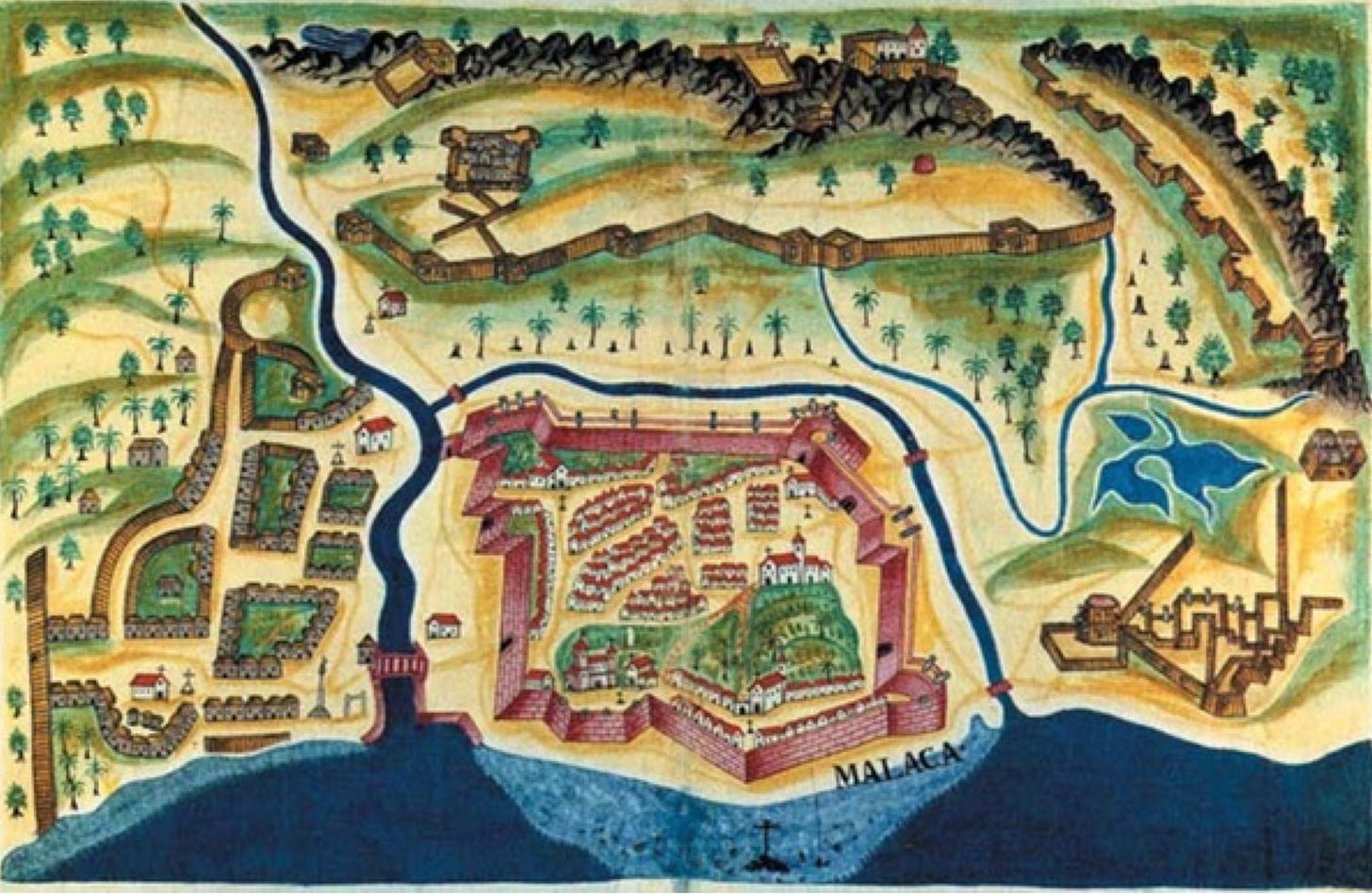

As Muslim merchants predicted, the Portuguese launched a triple assault on Malacca. The city was captured in 1511 by an armada of ships carrying fifteen hundred soldiers whose commander, Vicery Afonso d’Albuquerque, saw himself as an extension agent of the Portuguese state. That the invaders intended to assert permanent political control soon became clear. Albuquereue allegedly cried out to his men in the heat of battle that:

We [should] build fortress iin this city… and sustain it, and… this land [should] be brought under the dominion of the Portuguese, and the King D[om] Manuel be styled true king thereof.

Construction of a stone fortress was begun as soon as the battle was won, and it was kept well supplied with soldiers and cannon. The city was a Portuguese possession until the Dutch took it in the seventeenth century. Once secured, Malacca became a vital outpost used to establish other Portuguese enclaves in the Moluccas and on the China coast.

The conquest of Malacca, in turn, was an integral part of a grand scheme to capture gains from Indian Ocean trade. Political control of enclaves throughout the ocean basin was considered a necessary as well as desirable mans to an economic end. Albuquerque appealed to the profit motive as explicitly as one could: “If we take this trade of Malacca out of [the Moors’] hands, Cairo and Mecca are entirely ruined, and to Venice will no spiceries go except that which her merchants go and buy in Portugal.”

Portuguese actions also reveal the religious dimension of their drive for dominance. Albuquerque waited to launch his attack until the day of Saint James, the patron saint of the Iberian crusaders. That the crusading mentality was alive and well can be seen in his reference to “the great service which we shall perform to our Lord in casting the Moors out of the country, and quenching the fire of this sect of Mohamed so that it may never burst out again hereafter.” Non-Muslims were spared following the battle. But “of the Moors, [including] women and children, there died by the sword an infinite number, for no quarter was given to any of them.” A church was constructed, and in 1557 it became the Cathedral of the Bishop of Malacca. Priests working among non-Muslims in the local fishing community made many converts. The famous Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier visited the city in 1545 on his way from India to Japan.

By one estimate between half a million and a million people, from Mozambique to Japan, converted to Roman Catholicism by the end of the sixteenth century. Malacca’s history and its role as missionary way station to other parts of Asia illustrate the strong expansionist impulses of Euro-Christianity.

By examining actions, motivations, and institutions at a critical juncture of world history when representatives of the three leading candidates for global dominance were present at the same place and time, the case study of Malacca in 1511 tests—and supports—the book’s central proposition. The Portuguese were unlike the Chinese and Arabs in the number and variety of sectoral institutions at their dsposal, in the stretch of these institutions far from their home base, and in the way agents of different sectors worked together for mutually beneficial ends. The Malaccan case highlights not only the contrast between Europeans and others who might have formed equivalent empires, but also the empowering effects when cross-sectoral coalitions were assembled….

The case study also helps answer a secondary question…. why Europeans concentrated phase 1 settlement and conquest activities on the New World…. Portugal’s grand strategy in the Indian Ocean was to capture gains from a lucrative seaborne trade that had functioned for a long time. Malacca was valued as an enclave… profits literally floated past in the form of ships carrying spices, precious stones, textiles, chinaware, carvings, and so on through a narrow strait. There was no economic or strategic reason for Albuquerque to invade the Malayan interior….

In contrast, the Spaniards in the New World encountered no preexisting maritime trade. The wealth they sought would have to be captured at its source, deep in central and south American hinterlands. Vera Cruz… was seen not as an enclave facing the sea but as the staging area for an arduous march inland…. Spain could attain wealth in the New World only by conquering and settling… revolutionize the New World economies….

Portugal, having an essentially conservative economic agenda, felt no need to send settlers to Malacca or to set up plantations or prospect for minerals…. Spain, facing both the necessity and the opportunity in the Americas to design radically new patterns of extraction, production, and trade, exported its people… fostered large-scale, labor-intensive agricultural and mining operations…. Portuguese in Malacca… could prosper without altering indigenous political structures in the city’s immediate environs. Not so Cortes… who could not prosper unless state structures run by Europeans were in place to coerce indigenous peoples to labor long and hard for minimal reward…. A minimalist colonial strategy that worked well in phase 1 Malaya was not sufficient for New Spain.

Not until the nineteenth century did Europeans consider the Malayan interior worthy of their attention. Under British direction, exports from rich tin mines were increased and rubber plantations laid out… a plant Europeans had found in the New [World]… a mode of production perfected earlier in the Americas…. Europe’s concentration on transforming the New World in [European imperalism] phase 1 facilitated conquest and transformation of much of the Old World in [European imperalism] phase 3… LINK: <https://www.bradford-delong.com/2008/03/the-european--1.html>