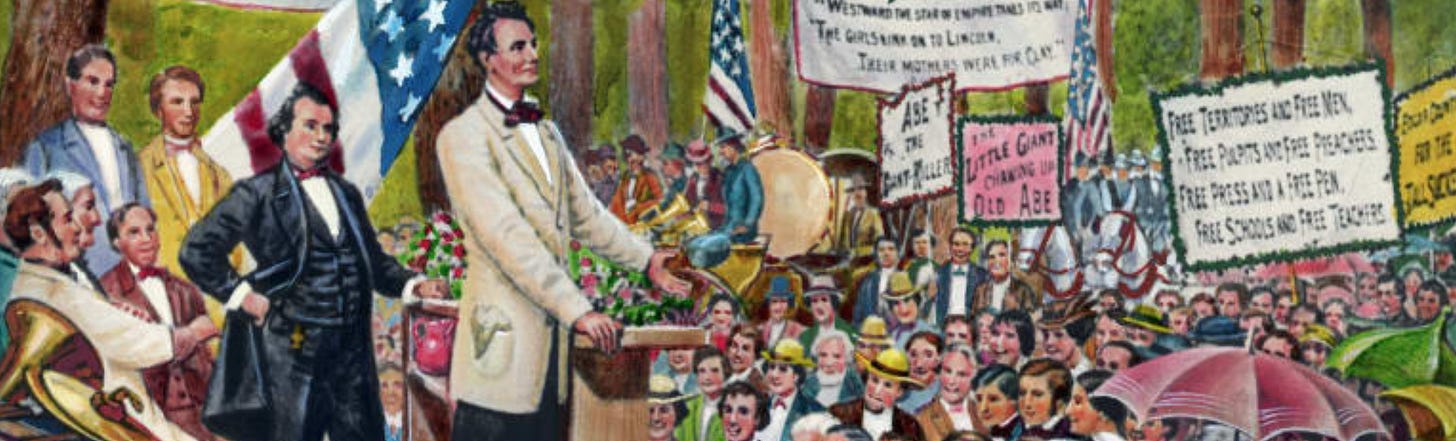

READING: Harry Jaffa (1959): Lincoln in þe Mid-1800s Wresting America from Its Þen-Probable Future of Herrenvolk Democracy

Why Harry Jaffa would puke if he saw those in Claremont, CA, who pretend to revere his name; from "Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates"

Harry Jaffa (1959): Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates: XX. The End of Manifest Destiny: ‘…Lincoln knew that the vast acquisitions of the Mexican War were only a foretaste of what Douglas himself believed to be in store if he ever gained control of the nation s foreign policy. Only a national commitment to confine slavery, Lincoln believed, would put an end to the drive for foreign conquest and domination... [given] the dynamism in the coincidence of the ambitions of Douglas and the slave power. It was this coincidence that repealed the Missouri Compromise.... Douglas did strike a bargain with the Southerners, and there was nothing in his policy or principles which inhibited him from indulging any requirement of slavery. That Douglas would have consented to the expansion of slavery as a means to other ends we can hardly doubt....

The fourth question Lincoln put to Douglas at Freeport has also been overshadowed by the famous second question. It, too, has a significance that can hardly be exaggerated. Lincoln asked: "Are you in favor of acquiring additional territory, in disregard of how such acquisition may affect the nation on the slavery question?" Here is an extract from Douglas's reply:

this is a young and growing nation. It swarms as often as a hive of bees, and... there must be hives in which they can gather and make their honey. In less than fifteen years, if the same progress that has distinguished this country for the last fifteen years continues, every foot of vacant land between this and the Pacific Ocean, owned by the United States, will be occupied. Will you not continue to increase at the end of fifteen years as well as now? I tell you, increase, and multiply, and expand, is the law of this nation s existence. You cannot limit this great republic by mere boundary lines, saying, thus far shalt thou go, and no further." Any one of you gentlemen might as well say to a son twelve years old that he is big enough, and must not grow any larger, and in order to prevent his growth put a hoop around him to keep him to his present size. What would be the result? Either the hoop must burst... or the child must die.

So it would be with this great nation. With our natural increase... with the tide of emigration that is fleeing despotism in the old world to seek a refuge in our own, there is a constant torrent pouring into this country that requires more land, more territory upon which to settle, and just as fast as our interests and our destiny require additional territory in the north, in the south, or in the islands of the ocean, I am for it, and when we acquire it will leave the people, according to the Nebraska Bill, free to do as they please on the subject of slavery and every other question…

Let us note that, according to this doctrine, the land area of the Western Hemisphere became usable only by being incorporated into the United. States!... Lincoln could see no reason in 1858 why every expansion of freedom would have to take place by an expansion of the boundaries of the United States. How Lincoln scorned Douglas's expansionism we may gather from the following rebuttal to Douglas's answer to his fourth Freeport question. It was delivered at Galesburg:

If Judge Douglas s policy upon this question succeeds, and gets fairly settled down, until all opposition is crushed out, the next thing will be a grab for the territory of poor Mexico, and invasion of the rich lands of South America, then the adjoining islands will follow, each one of which promises additional slave fields. And this question is to be left to the people of those countries for settlement. When we shall get Mexico, I don't know whether the Judge will be in favor of the Mexican people that we get with it settling this question for themselves and all others; because we know the Judge has a great horror for "mongrels", and I understand that the people of Mexico are most decidedly a race of "mongrels". I understand that there is not more than one person there out of eight who is pure white, and I suppose from the Judge's previous declaration that when we get Mexico or any considerable portion of it, that he will be in favor of these "mongrels" settling this question, which would bring him some¬ what into collision with his horror of an inferior race…

The ugly potentialities of a policy of lebensraum combined with racial supremacy should hardly need explanatory comment today. The accents of sarcasm in the foregoing extract can scarcely escape notice. Of the "mongrels" to the south Douglas had spoken thus at Springfield, July 1, 1858:

We are witnessing the result of giving civil and political rights to inferior races in Mexico, Central America, in South America, and in the West India Islands. Those young men who went from here to Mexico to fight the battles of their country in the Mexican war, can tell you the fruits of negro equality with the white man. They will tell you that the result of that equality is social amalgamation, demoralization and degradation, below the capacity for self-government…

Douglas's white-supremacy American empire, would have been a very different polity from anything envisaged in the pristine purity of the republican ideal of the Founding Fathers. There would have been precious little "popular sovereignty" for the natives for whom Douglas had such contempt. And there might be many American states today in which, as in the case of the French in Algeria, a privileged minority would be engulfed in the swirling tides of hatred of an unprivileged majority of a different complexion.

The problem of racial adjustment in America today is of an order of magnitude that we could hardly exaggerate. And this problem, as every informed person knows, although dramatized by the struggle of the Negro, is not limited to the Negro. Indians, Mexicans, Orientals have all had a desperate struggle, varying in times, places, and intensity, to achieve the dignity which our fundamental law and principles hold out to all. Aspiration must, as Lincoln implied in his standard maxim doctrine, always transcend fulfillment. Yet it is essential that the possibility of fulfillment does not fall so far short of the aspiration as to make it not a source of hope but a mockery.

Douglas's formula for solving the slavery question, in which the nation was already hopelessly entangled, would have made that question infinitely more complicated. It is almost inconceivable that democratic processes could have survived such complications.

And we can only shudder to think what the twentieth century would be like if the United States had entered it as first and foremost of totalitarian powers.

The only moral justification of Douglas's policy—as of revisionist historiography—is a tacit belief in the idea of progress, an idea that economic forces were "inevitably working for freedom", both on the plains of Kansas and elsewhere. Only such a belief could justify the principle that all harsh moral alternatives were to be avoided, that one could safely "agree to disagree". The silent forces of history were working for freedom, if only the politicians would give them time.

Lincoln’s whole policy, on the contrary, was a denial that things would take care of themselves, that progress would result from anything but man’s foresight, judgment, and courage. The impulse of the Revolution had been a mighty one, Lincoln believed, and great things had been achieved because of it. But the spirit of '76 and the spirit of Nebraska were utter incompatibilities. The Nebraska bill could never even have been considered if there had not been an enormous change in public opinion, a change for the worse that augured still further changes for the worse, changes which portended the utter extinction of a weary mankind's hope that there might at last be a demonstration of man's capability to govern himself.

To avert these changes no reliance could be placed on anything so absurd as "soil and climate." The only reliance, the only rock upon which man's political salvation might be built, was man's moral sense, the determination of some men to be free, and the awareness that no man can rightfully achieve freedom for himself or, in the presence of a just God, long retain his freedom if he would deny to any other man, of whatever race or nation, the right to equal freedom.

Crisis of the House Divided is both a great and a crazy book. It is, on one level, Jaffa’s attempt to read the minds of Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln—what thoughts lay behind the words they spoke. Or, perhaps, it is something else: it is Jaffa’s attempt to read the minds of what those who heard the words of Douglas and Lincoln, and took them seriously and into their hearts, would have thought in the fullness of time and historical development as those words wrought their influence.

And there is more: Jaffa’s reading assumes that the speaker (or the listener) thinks in the close-reading Talmudic-philosophical mode of Leo Strauss.

Not, I hasten to add, that Jaffa’s image of the speaker or the listener thinks as Leo Strauss did. Leo Strauss was, as he boasted: fascist, authoritarian, imperial. Strauss’s vision of a good social order was one that scorned hoi polloi and their demagogic panderer-masters/slaves, whether socialist or Nazi. It was one in which rule was handled by gentlemen—think of the Athenian aristocrats of the classical age who admired Spartan discipline—advised by philosophers, or at least taught by philosophers not to be pointlessly and counterproductively cruel. Thus when Strauss reads an author he likes, he is smart enough to twist what they write, via selective shifts of focus and attention, strongly toward that doctrine. And, as Sokrates said, the writings cannot then defend themselves against misinterpretation.

So is this procedure in the hands of Harry Jaffa bound to lead to similar misinterpretative disasters? I think not. Very few of the authors whom Srrauss pounds into his Procrustean beds share Strauss’s fascist, authoritarian, imperial values. But Jaffa shares Lincoln’s democratic, egalitarian, republican, American values. And Jaffa understands Douglas’s expansionist, imperial, populist, American values. And they were both very smart men, eloquent, and very clever at using words to say exactly what they wanted to say, and no more.

Thus both Lincoln and Douglas—even the stenographic-reported versions of their words published in the newspapers, which is what we now have—repay a close reading undertaken with Talmudic care, and an awareness of and concern for the implications and ramifications of their positions, if it is carried out by someone able to empathize with their project, and willing to give them a fair reading via a hermaneutics of charity.

And, IMHO, Jaffa is able to do this.

And so I think his procedure produces many insights.

Do note that Jaffa is not unique here in so filling-in the thoughts and actions according to this particular model. He is tilling fertile ground. After all, Ronald Syme wrote his biography of Augustus and his age, The Roman Revolution, as if Augustus had thought like Mussolini Syme’s book is the best book on the age of Augustus,

Brad, you have been on a roll lately with excellent and thoughtful commentary. This is a particularly appropriate choice to demonstrate the stylistic and moral differences between Douglas and Lincoln. I am always amazed at how Douglas wove complex and elegant arguments devoid of decency that withered in the face of Lincoln’s simple logic and moral consistency.

And, once again...THIS is why I subscribe to this substack.