READING: John Lippert on þe Idiocy of þe Chicago School in Late 2008

No. There is neither a transcript nor a video nor an audio of John Cochrane's 2008 CRISP Forum keynote at the Gleacher Center. It appears to have been deep-sixed. All we have of it appears to be...

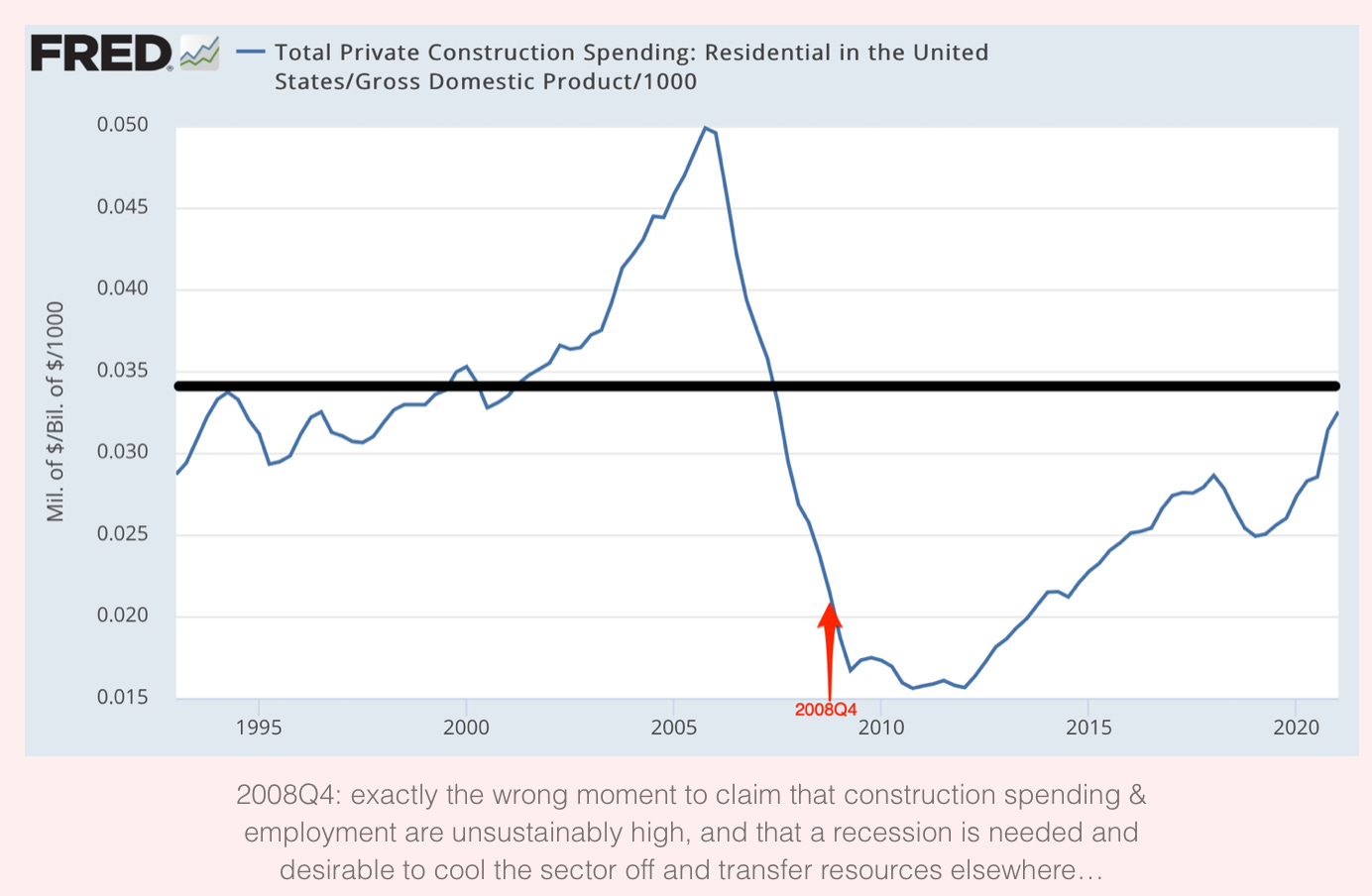

…Cochrane’s declaration—made at a time when the share of the U.S. labor force in construction was below its long-run average and had been below its long-run average for fifteen months—that: “we should have a recession. People who spend their lives pounding nails in Nevada need something else to do.” No recognition at all that the structural-adjustment climb-down from the housing boom had already taken place. No recognition that structural adjustment takes place by pulling people into high-value jobs, not by pushing them out of low-value jobs into zero-value non-jobs. No recognition at all:

John Lippert (2008–12–23): Bloomberg: ‘John Cochrane was steaming as word of U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson’s plan to buy $700 billion in troubled mortgage assets rippled across the University of Chicago in September. Cochrane had been teaching at the bastion of free-market economics for 14 years and this struck at everything that he—and the school—stood for. “We all wandered the hallway thinking, How could this possibly make sense?” says Cochrane, 51, recalling his incredulity at Paulson’s attempt to prop up the mortgage industry and the banks that had precipitated the housing market’s boom and bust.

During a lunch held on a balcony with a view of Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, Cochrane, son-in-law of Chicago efficient-market theorist Eugene Fama, and some colleagues made their stand. They wrote a petition attacking Paulson’s proposal, sent it to economists nationwide and collected 230 signatures. Republican Senator Richard Shelby of Alabama waved the document as he scorned the rescue. When Congress rejected it on Sept. 29, Cochrane fired off congratulatory e-mails. The victory was short-lived. Lawmakers approved the plan four days later, swayed by what Cochrane calls a pinata of pork-barrel amendments.

“We should have a recession,” Cochrane said in November, speaking to students and investors in a conference room that looks out on Lake Michigan. “People who spend their lives pounding nails in Nevada need something else to do.”

At the University of Chicago, once ascendant free-market acolytes are finding themselves in an unusual role: They’re battling a wave of government intervention more sweeping than any since the Great Depression as the U.S. struggles with the worst recession in seven decades. By the end of November, the government had committed $8.5 trillion, or more than half the value of everything produced in the country in 2007, to save the financial system. The European Union had ponied up more than $3 trillion to guarantee bank loans and provide capital to lenders. And China had unveiled a $586 billion stimulus plan and its biggest interest-rate cut in 11 years.

The intrusion is anathema to the so-called Chicago School of economics and its patriarch, the late Milton Friedman. For half a century, Chicago’s hands-off principles have permeated financial thinking and shaped global markets, earning the university 10 Nobel Memorial Prizes in Economic Sciences starting in 1969, more than double the four each won by Columbia University, Harvard University, Princeton University and the University of California, Berkeley. Chicago’s laissez-faire imprint underpins everything from U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s 1981 tax cuts and the fall of communism that decade to quantitative investment strategies. In 1972, Friedman helped persuade U.S. Treasury Secretary George Shultz, former dean of Chicago’s business school, to approve the first financial futures contracts in foreign currencies. Such derivatives grew more complex after Chicago economists created the mathematical formulas to price them, helping spawn a $683 trillion market that’s proved to be a root of today’s financial system breakdown. On Dec. 16, the U.S. Federal Reserve cut its target lending rate to as low as zero for the first time and said it will buy mortgage- backed securities.

Friedman, who died in 2006 at age 94, defined the Chicago School in 1974 as he spoke to a board of trustees dinner. “‘Chicago’ stands for a belief in the efficacy of the free market as a means of organizing resources, for skepticism about government intervention into economic affairs,” he said. Friedman was explaining a movement that had taken hold in the U.S. and was percolating in Europe and South America. “By the mid–1970s, there was a whole generation in government and academia who’d trained at Chicago or places influenced by it,” says Ross Emmett, a Michigan State University professor who’s written three books on the school. Today, 10 percent of Chicago undergraduates study economics. Alumni of Chicago’s graduate business school, now called the Booth School of Business, run states and companies. Jon Corzine, the former chief executive officer of Goldman, Sachs & Co. who earned his MBA in 1973, is governor of New Jersey. Peter Peterson, who graduated with an MBA in 1951, co-founded Blackstone Group LP, the world’s largest private equity firm. David Booth, a 1971 MBA graduate for whom the school is now named, donated $300 million in November, the largest endowment given to the university.

Booth, who founded Dimensional Fund Advisors Inc., bases his funds on Fama’s theory that a market digests information affecting prices so well that even professional investors can’t outsmart it for long. Even with his U.S. Micro Cap Portfolio fund down 40 percent in 2008 through Dec. 22, Booth says quantitative investing is less vulnerable during a slump than stock picking that relies on human judgment. “This supports our theory in that predicting the market is even more difficult than we expected,” he says. Unlike Booth, 62, much of the academic world is reassessing Chicago School hallmarks. That’s true even in the limestone buildings on the 211-acre (85-hectare) Hyde Park campus in which professors teach Friedman’s theories.

On Oct. 14, about 250 students and professors debated an administration-backed plan for a $200 million research center to be named for Friedman. The protesters argued that the institute would enshrine policies that have brought economies near collapse. “When Friedman’s Platonic ideas of free-market virtues are put into practice, they have too often generated a systemic orgy of competitive greed – whose remedies, ironically, entail countermeasures of nationalization,” Marshall Sahlins, an emeritus professor of anthropology, said during the debate, speaking in a room adorned with murals of female students parading through the campus in medieval gowns. Sahlins, 77, noted a few weeks later socialist and capitalist countries alike are regulating or nationalizing financial institutions in a rebuff to Friedman. Off campus, the global meltdown is stirring anti-Chicago economists, who were voices in the wilderness during decades of lax government oversight of markets. Joseph Stiglitz, who won one of Columbia’s economics Nobels, says the approach of Friedman and his followers helped cause today’s turmoil.

“The Chicago School bears the blame for providing a seeming intellectual foundation for the idea that markets are self- adjusting and the best role for government is to do nothing,” says Stiglitz, 65, who received his Nobel in 2001. University of Texas economist James Galbraith says Friedman’s ideology has run its course. He says hands-off policies were convenient for American capitalists after World War II as they vied with government-favored labor unions at home and Soviet expansion overseas. “The inability of Friedman’s successors to say anything useful about what’s happening in financial markets today means their influence is finished,” he says. Instead, Galbraith, 56, says policy-makers are rediscovering the ideas of his father, Harvard professor John Kenneth Galbraith, and economist John Maynard Keynes of the University of Cambridge. Keynes, who died in 1946, argued that governments should spend to combat the unemployment that free markets tolerate. Galbraith, who died in 2006, rejected mathematical models and technical analyses as divorced from reality….

Already, some of the university’s top economists have abandoned hard-line Friedmanism for the middle ground. Douglas Diamond, a finance professor at Chicago since 1979, declined to sign Cochrane’s petition damning Paulson’s bailout. Diamond says he knew the Sept. 29 vote against the rescue would spur investors to pull assets from banks. He says governments have no choice but to provide safety nets for banks and tougher oversight. “The vote was the beginning of people believing crazy stuff, like the U.S. might find it politically expedient to let its financial system go,” Diamond, 55, says.

Robert Lucas, a Chicago economist who won a Nobel in 1995 for a theory that argued against governments trying to fine-tune consumer demand, says deregulation may have gone too far. Depression-era laws that separated commercial and investment banks helped depositors decide if they wanted secure accounts or riskier investments. Today, without these distinctions, people can’t be sure if their investments, or those of their customers, are safe. “I’m changing my views on bank regulation every week,” Lucas, 71, says. “It was an area I saw as under control. Now I don’t believe that.” Lucas says he voted for Obama, the only Democrat besides Bill Clinton he’d supported in 44 years. He concluded the candidate was comfortable talking with professional economists. He describes Goolsbee, whom he has met in faculty workshops, as a serious scholar….

The university got its start in 1892 as a haven for researchers, not would-be managers. William Rainey Harper, a Bible scholar who taught at Yale, attracted oil magnate John D. Rockefeller as his benefactor. Harper broke with then prevailing Ivy League practices by hiring Jews, finance professor Fama says. By 1946, Chicago was luring stars such as Enrico Fermi, father of the self-sustaining nuclear reaction. Friedman’s parents were Jews who emigrated from what’s now Ukraine. When he joined the faculty in 1946, he allied with Friedrich Hayek, a London School of Economics professor who later transferred to Chicago. They sought to discredit Keynes, who argued that deficits in government budgets could revive demand in recessions. They viewed rising government power as a step toward left-wing totalitarianism and wanted to stop it, says Philip Mirowski, a University of Notre Dame economist….

Fama, 69, who favors casual shirts and chinos on campus, joined the Chicago faculty in 1963. When he opened his financial theory class on Sept. 29, the day Congress voted down Paulson’s bailout, he placed efficient-market equations from his 1976 textbook on an overhead projector. Fama says he never denied the possibility of unexpected events even though he’d spent a lifetime showing that markets effectively digest information. He was stunned that American International Group Inc., once the world’s largest insurer, sold $441 billion in unhedged and undercapitalized insurance on securitized debt, much of it tied to mortgage values. “No one expected a player like AIG to take a long position and not hedge themselves,” Fama says. He says the government may have been able to stabilize the U.S. financial system at a lower cost by letting AIG collapse.

LINK: <https://delong.typepad.com/egregious_moderation/2008/12/john-lippert-on-the-chicago-school.html>

(Remember: You can subscribe to this… weblog-like newsletter… here:

There’s a free email list. There’s a paid-subscription list with (at the moment, only a few) extras too.)

It's too late! Chicago may have reformed, but its legacy will be with us for several generations. The business school is now at the center of the modern university, with the economics department a prestige satellite. At least the physicists who preceded them were indulgent to the humanists, if not quite comprehending.