READING: Mark Silk: Did John Adams Out Thomas Jefferson & Sally Hemings?

John Adams, Sally Hemings as "Egeria", and Thomas Jefferson...

Mark Silk: Did John Adams Out Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings?: ‘The first eight months of 1802 were mercifully dull for President Jefferson. France and England signed a peace treaty, reopening European and Caribbean ports to American commerce. The Navy was making headway against Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean. West Point was established. A prime concern was paying off the national debt. The bitter election of 1800 was fading from memory.

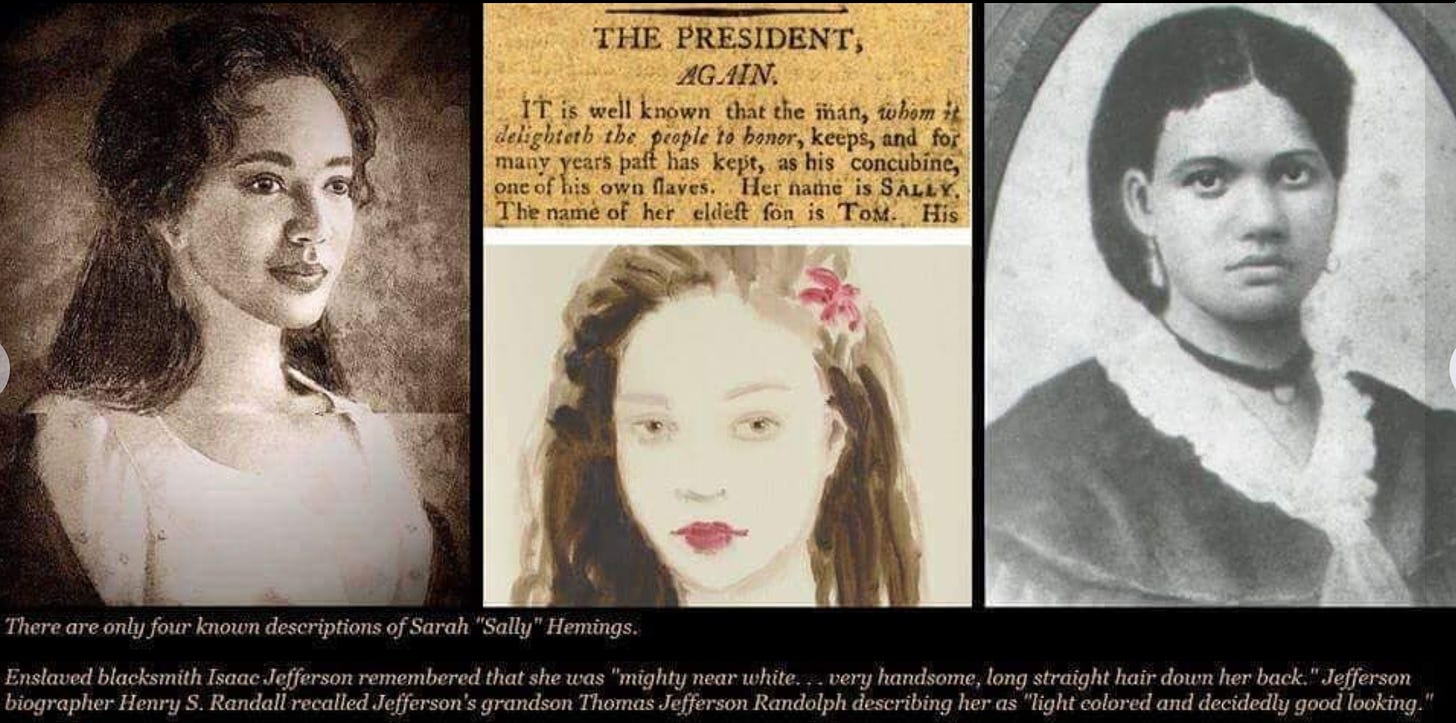

Then, in the September 1 issue of the Richmond Recorder, James Callender, a notorious journalist, reported that the president of the United States had a black slave mistress who had borne him a number of children. “IT is well known that the man, whom it delighteth the people to honor, keeps, and for many years past has kept, as his concubine, one of his own slaves,” the story began. “Her name is SALLY.”

Federalist newspapers from Maine to Georgia reprinted the story. Racist poems were published about the president and “Dusky Sally.” Jefferson’s defenders were more muted, waiting in vain for the denial that never came from the Executive Mansion. The scandal rocked the fledgling nation.

How “well known” was the relationship between Jefferson and Hemings? Callender wrote that it had “once or twice been hinted at” in newspapers, as indeed it was in 1800 and 1801. And in reaction to his muckraking, the Gazette of the United States said it had “heard the same subject freely spoken of in Virginia, and by Virginia Gentlemen.” But while scholars have combed the sources, they have identified no specific written reference to the Jefferson-Hemings liaison prior to the appearance of Callender’s scandalous report.

I believe I have found two such references. They precede the exposé by more than eight years, and they come from the pen of none other than Jefferson’s old friend and political rival John Adams. In letters to his sons Charles and John Quincy in January of 1794, Adams points to the relationship between the sage of Monticello and the beautiful young woman known around the plantation as “Dashing Sally.” The references have escaped notice until now because Adams used a classical allusion whose significance historians and biographers have failed to appreciate.

Adams’ letters offer tangible evidence that at least one of the country’s leading political families was aware of the Jefferson-Hemings relationship long before the scandal broke. The documents cast new light on the question of elite awareness of the relationship, on the nature of the press in the early republic, and on Adams himself.

Jefferson resigned as George Washington’s secretary of state on the last day of 1793. It had not been a good year. His efforts to force his hated rival Alexander Hamilton out of the cabinet for financial misconduct failed miserably. Continuing to support the French Revolution despite the guillotining of the king and queen and the blossoming of the Terror, he alienated Adams and was disappointed by Washington’s proclamation of American neutrality in France’s latest war with England. At 50 years old, he was eager to return to his beloved Virginia estate to live as a gentleman farmer and philosopher.

Adams, the vice president, refused to believe that his estranged friend was really done with public life. In letters to his two eldest sons, he sourly assessed the man he was convinced would challenge him to succeed Washington as president. On January 2 he wrote to Charles:

Mr Jefferson is going to Montecello to Spend his Days in Retirement, in Rural Amusements and Philosophical Meditations—Untill the President dies or resigns, when I suppose he is to be invited from his Conversations with Egeria in the Groves, to take the Reins of the State, and conduct it forty Years in Piety and Peace…

On January 3 he wrote to John Quincy at greater length, enumerating seven possible motives for Jefferson’s resignation.

(5) Ambition is the Subtlest Beast of the Intellectual and Moral Field. It is wonderfully adroit in concealing itself from its owner, I had almost said from itself. Jefferson thinks he shall by this step get a Reputation of an humble, modest, meek Man, wholly without ambition or Vanity. He may even have deceived himself into this Belief. But if a Prospect opens, The World will see and he will feel, that he is as ambitious as Oliver Cromwell though no soldier. (6) At other Moments he may meditate the gratification of his Ambition; Numa was called from the Forrests to be King of Rome. And if Jefferson, after the Death or Resignation of the President should be summoned from the familiar Society of Egeria, to govern the Country forty Years in Peace and Piety, So be it…

In the vernacular of the time, “conversation” was a synonym for sexual intercourse and “familiar” was a synonym for “intimate.” The obvious candidate for the person whose conversation and familiar society Jefferson would supposedly be enjoying at his bucolic home is Sally Hemings.

But who was Egeria, and how confident can we be that Adams intended Hemings when he invoked her name?

Egeria is a figure of some importance in the mythical early history of ancient Rome. According to Livy and Plutarch, after the death of the warlike Romulus, the senators invited a pious and intellectual Sabine named Numa Pompilius to become their king. Accepting the job with some reluctance, Numa set about establishing laws and a state religion.

To persuade his unruly subjects that he had supernatural warrant for his innovations, Numa claimed that he was under the tutelage of Egeria, a divine nymph or goddess whom he would meet in a sacred grove. The stories say she was not just his instructor but also his spouse, his Sabine wife having died some years before. “Egeria is believed to have slept with Numa the just,” Ovid wrote in his Amores.

Age 40 when he became king, Numa reigned for 43 years—a golden age of peace for Rome during which, in Livy’s words, “the neighboring peoples also, who had hitherto considered that it was no city but a bivouac that had been set up in their midst, as a menace to the general peace, came to feel such reverence for them, that they thought it sacrilege to injure a nation so wholly bent upon the worship of the gods.”

Adams, who was well versed in Latin and Greek literature, had every reason to feel pleased with his comparison. Like Rome at the end of Romulus’ reign, the United States was a new nation getting ready for its second leader. Jefferson would be the American Numa, a philosophical successor to the military man who had won his country’s independence. Like Numa, Jefferson was a widower (his wife, Martha, died in 1782) who would prepare himself for the job by consorting with a nymph, his second wife, in a grove that was sacred to him.

I asked Annette Gordon-Reed, the Harvard scholar and author of _Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy_, what she made of the Adams references. “While the two letters to his sons do not definitively prove that Adams knew about the Jefferson-Hemings liaison in early 1794,” Gordon-Reed said in an email, “this elucidation of the allusion to Egeria makes that an intriguing possibility.”

One didn’t require a classical education to grasp the Egeria allusion in the early 1790s. In 1786, the French writer Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian had published _Numa Pompilius, Second Roi de Rome_, a romantic novel dedicated to Marie Antoinette—she liked it—and intended as a guide for an enlightened monarchy in France. (“People will believe I’ve written the story / Of you, of Louis, and of the French,” Florian’s dedicatory poem declares.) Soon translated into English, Spanish and German, the novel became a runaway best seller in the North Atlantic world.

It was while researching a novel of my own about the life and afterlife of Numa and Egeria that I happened upon the allusions in the two Adams letters. As a student of religion in public life, I have long been interested in Numa as an exemplary figure in the history of Western political thought from Cicero and St. Augustine to Machiavelli and Rousseau.

In fact, John Adams had made a point of invoking Numa and his divine consort in the three-volume _Defence of the Constitutions of Government_ of the United States of America, which he published while serving as minister to England in 1787. “It was the general opinion of ancient nations, that the divinity alone was adequate to the important office of giving laws to men,” he writes in the preface. “Among the Romans, Numa was indebted for those laws which procured the prosperity of his country to his conversations with Egeria.” Later in the work he explains, “Numa was chosen, a man of peace, piety, and humanity, who had address enough to make the nobles and people believe that he was married to the goddess Egeria, and received from his celestial consort all his laws and measures…”

In the _Defence_, Adams was at pains to inform the world that, unlike other nations past and present, the recently united American states “have exhibited, perhaps, the first example of governments erected on the simple principles of nature.” In other words, no Egerias need apply: “It will never be pretended that any persons employed in that service had any interviews with the gods, or were in any degree under the inspiration of heaven, any more than those at work upon ships or houses, or labouring in merchandize or agriculture: it will for ever be acknowledged that these governments were contrived merely by the use of reason and the senses.”

Jefferson was the American avatar of Enlightenment rationality, a staunch opponent of the government establishment of religion, and the Washington administration’s foremost advocate of war with the Barbary pirates. Adams’ portrayal of him consulting with a goddess in order to govern “in Piety and Peace” was sharply pointed on all counts. But did he intend the goddess in question to refer to Sally Hemings?

There’s good reason to think so. Seven years earlier, Jefferson had arranged for his 8-year-old daughter, Mary, to join him and his elder daughter, Martha, in Paris. Hemings, a slave who was also a half-sister of Jefferson’s late wife, accompanied Mary on the trans-Atlantic passage to England; upon their arrival, the two girls went to stay with the Adamses in London. Hemings was then 14 years old but, tellingly, Abigail Adams thought she was 15 or 16.

Writing Jefferson that the two had arrived, Abigail Adams took them under her wing until an emissary showed up two weeks later to convey them to Paris, where Jefferson almost certainly began having sex with Hemings. So in 1787 John Adams had seen for himself that Jefferson had a nubile beauty in his possession. By the end of 1793, John Quincy and Charles presumably would have been aware of it, too. Otherwise, the sexual allusion to Egeria would have been lost on them.

Significantly, John Adams did not allude to the matter when he wrote to Abigail at around the same time. She and Jefferson had something of a mutual admiration society, after all. “My Love to Thomas,” she wrote her husband on the very day that Jefferson resigned as secretary of state (though she wasn’t yet aware of that). Despite the two men’s political rivalry, she maintained a high regard for Jefferson through the 1790s, describing him as a man of “probity” in a letter to her sister. So while John Adams, in Philadelphia, did not refrain from criticizing Jefferson in his January 6, 1794, letter to Abigail, in Massachusetts, he did so with care.

Jefferson went off Yesterday, and a good riddance of bad ware. I hope his Temper will be more cool and his Principles more reasonable in Retirement than they have been in office. I am almost tempted to wish he may be chosen Vice President at the next Election for there if he could do no good, he could do no harm. He has Talents I know, and Integrity I believe: but his mind is now poisoned with Passion Prejudice and Faction.

There was no mention of Numa and Egeria. As I see it, John knew that his wife would not be amused by the insinuation that Jefferson was retiring to an intimate relationship with the maidservant she had cared for in London seven years earlier. That joke was reserved for the boys.

A political eon passed between the vice president’s private joke and the presidential scandal. In 1796, Jefferson was narrowly defeated for the presidency by Adams and, under Article II of the Constitution (changed in 1804), indeed became vice president, having received the second-largest number of electoral votes. Four years later, he returned the favor, besting Adams in perhaps the ugliest presidential election in American history.

By then, Callender had won his muckraking spurs by publishing the story of Alexander Hamilton’s affair with a married woman and subsequent illicit financial arrangement with the woman’s husband. Jefferson was sufficiently impressed to provide the journalist with financial support to keep up his anti-Federalist work. But in May of 1800, Callender was convicted and sentenced to nine months in prison under the Sedition Act for “The Prospect Before Us,” a tract alleging pervasive corruption in the Adams administration. After his release, he approached Jefferson and asked to be appointed postmaster of Richmond. Jefferson refused. Callender traveled to Charlottesville and ferreted out the Hemings story, published under the headline “The President, Again.”

One of the more scurrilous commentaries on the story came from John Quincy Adams. On October 5, he sent his youngest brother, Thomas Boylston, a letter with an imitation of Horace’s famous ode to a friend who had fallen in love with his servant girl that begins: “Dear Thomas, deem it no disgrace / With slaves to mend thy breed / Nor let the wench’s smutty face / Deter thee from the deed.”

In his letter John Quincy writes that he had been going through books of Horace to track down the context of a quotation when what should drop out but this poem by, of all people, Jefferson’s ideological comrade in arms Tom Paine, then living in France. John Quincy professed bafflement that “the tender tale of Sally” could have traveled across the Atlantic, and the poem back again, within just a few weeks. “But indeed,” he wrote, “Pain being so much in the philosopher’s confidence may have been acquainted with the facts earlier than the American public in general.”

Historians have assumed that John Quincy, an amateur poet, composed the imitation ode in the weeks after Callender’s revelation hit the press. But in light of his father’s letters, it is not impossible that he had written it before, as his arch little story of its discovery implied. Thomas Boylston arranged to have his brother’s poem published in the prominent Federalist magazine The Port-Folio, where it did in fact appear under Paine’s name.

The Adamses never dismissed Callender’s story as untrue. No direct comment from Abigail Adams has come to light, but Gordon-Reed argues in The Hemingses of Monticello that the scandal deepened her estrangement from Jefferson after the bitter 1800 election. When Mary Jefferson died in 1804, Abigail wrote Thomas a chilly condolence letter in which she described herself as one “who once took pleasure in subscribing herself your friend.”

John Adams, in an 1810 letter to Joseph Ward, refers to James Callender in such a way as to imply that he did not consider the Hemings story credible. “Mr Jeffersons ‘Charities’ as he calls them to Callender, are a blot in his Escutchion,” he writes. “But I believe nothing that Callender Said, any more than if it had been Said by an infernal Spirit.” In the next paragraph, however, he appears more than prepared to suspend any such disbelief.

Callender and Sally will be remembered as long as Jefferson as Blotts in his Character. The story of the latter, is a natural and almost unavoidable Consequence of that foul contagion (pox) in the human Character Negro Slavery. In the West Indies and the Southern States it has the Same Effect. A great Lady has Said She did not believe there was a Planter in Virginia who could not reckon among his Slaves a Number of his Children. But is it Sound Policy will it promote Morality, to keep up the Cry of such disgracefull Stories, now the Man is voluntarily retired from the World. The more the Subject is canvassed will not the horror of the Infamy be diminished? and this black Licentiousness be encouraged?…

Adams goes on to ask whether it will serve the public good to bring up the old story of Jefferson’s attempted seduction of a friend’s wife at the age of 25, “which is acknowledged to have happened.” His concern is not with the truth of such stories but with the desirability of continuing to harp on them (now that there is no political utility in doing so). He does not reject the idea that Jefferson behaved like other Virginia planters.

Adams’ sly joke in his 1794 letters shows him as less of a prude than is often thought. It also supports Callender’s assertion that the Jefferson-Hemings relationship was “well known,” but kept under wraps. It may be time to moderate the received view that journalism in the early republic was no-holds-barred. In reality, reporters did not rush into print with scandalous accusations of sexual misconduct by public figures. Compared with today’s partisan websites and social media, they were restrained. It took a James Callender to get the ball rolling.

John Adams’ reference to Jefferson’s Egeria put him on the cusp of recognizing a new role for women in Western society. Thanks largely to Florian’s 1786 best seller, the female mentor of a politician, writer or artist came to be called his Egeria. That was the case with Napoleon, Beethoven, Mark Twain, Andrew Johnson and William Butler Yeats, to name a few. In Abigail, Adams had his own—though so far as I know she was never referred to as such. It was a halfway house on the road to women’s equality, an authoritative position for those whose social status was still subordinate.

Gordon-Reed has criticized biographers who insist that it is “ridiculous even to consider the notion that Thomas Jefferson could ever have been under the positive influence of an insignificant black slave woman.” Ironically, Adams’ sarcastic allusion conjures up the possibility. Did Sally Hemings, Jefferson’s French-speaking bedmate and well-organized keeper of his private chambers, also serve as his guide and counselor—his Egeria? The question is, from the evidence we have, unanswerable.

In the last book of his Metamorphoses, Ovid portrays Egeria as so inconsolable after the death of Numa that the goddess Diana turns her into a spring of running water. When Jefferson died in 1826, he and Hemings, like Numa and Egeria, had to all intents and purposes been married for four decades. Not long afterward, his daughter Martha freed Hemings from slavery, as her children had been freed before her.

We do not know if, as she celebrated her liberation, she also mourned her loss. But we can be confident that her name, like Egeria’s, will forever be linked with her eminent spouse, as John Adams predicted.

LINK: <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/john-adams-out-thomas-jefferson-sally-hemings-180960789/>

(Remember: You can subscribe to this… weblog-like newsletter… here:

There’s a free email list. There’s a paid-subscription list with (at the moment, only a few) extras too.)

Yes: since the conjecture is that the… [insert adjective here] relationship started in Paris, that is a problem for the conventional conjecture

The big problem with Callendar's credibility has been that his specific claim -- Jefferson fathered a son on Sally Hemings around 1790 or so -- has been refuted by the DNA evidence. Her first confirmed child (presumably by Jefferson) was born in 1796 and the rest followed in a natural sequence until 1804 (dates off memory). So the question is, why no children before 1796 if she was his mistress during that time?

This hardly disproves the relationship; it merely suggests that it may not have begun early enough for some of these allusions to have been true. But this certainly is new evidence and it's very interesting.