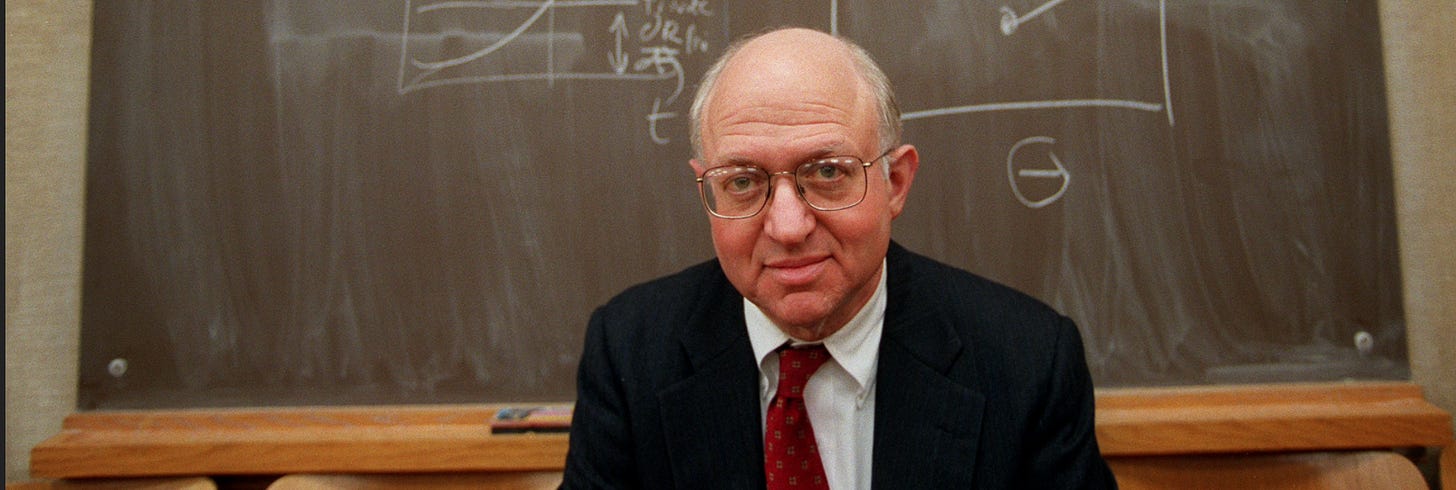

READING: Þe Ur-Text of þe Neoliberal Turn: My Teacher Marty Feldstein (1980)

Martin Feldstein (1980): The American Economy in Transition: Introduction

I greatly enjoy and am, in fact, driven to write Grasping Reality—but its long-term viability and quality do depend on voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. I am incredibly grateful that the great bulk of it goes out for free to what is now well over ten-thousand subscribers around the world. If you are enjoying the newsletter enough to wish to join the group receiving it regularly, please press the button below to sign up for a free subscription and get (the bulk of) it in your email inbox. And if you are enjoying the newsletter enough to wish to join the group of supporters, please press the button below and sign up for a paid subscription:

Martin Feldstein (1980): The American Economy in Transition: Introduction: 'The postwar period began in an atmosphere of doubt and fear. Many economists believed that the nation would slip back into the deep recession from which it had escaped only as the war began. In the decade between 1929 and 1939, real gross national product (GNP) had not grown at all, and the official unemployment rate had reached one-fourth of the labor force. During the war, the economy had returned to full or overfull use of its capacity: real GNP rose 75 percent between 1939 and 1944, while the unemployment rate fell to less than 2 percent. Even many optimists worried that demobilization and the transition to a civilian economy would lead to a new period of long-term stagnation caused by inadequate demand.

Real output did decline as the war ended, and the unemployment rate did begin to rise. Real GNP fell by nearly 20 percent between 1944 and 1947. As ten million men and women left the armed forces, total employment (civilian and armed forces combined) declined by nearly 10 percent and the unemployment rate rose to nearly 4 percent. But the fears and doubts of the "secular stagnationists" were unwarranted. After 1947 the economy began a period of remarkable growth and stability. In the next decade, real GNP rose 45 percent, and in the decade that followed another 48 percent. In only one of those twenty years did real GNP fall by as much as 1 percent, and that was in 1954, when military spending had been sharply reduced.

This sustained and rapid expansion had occurred with a relatively stable price level; the annual rise in the consumer price index averaged only 2 percent. The first two decades of the postwar period were a time of unsurpassed economic prosperity, stability, and optimism.

The contrast between the strength and achievement of the economy during those years and its poor record since then signals a major change in the performance of the economy over the postwar period. At the aggregate level, real GNP growth slowed from an annual rate of 3.9 percent between 1947 and 1967 to only 2.9 percent between 1967 and 1979. The growth of productivity per man-hour in the private business sector dropped from an annual rate of 3.2 percent during 1947-67 to less than 1.5 percent since 1967 and less than 1 percent since 1973. The average unemployment rate rose from 4.7 percent of the labor force to 5.8 percent. The average rate of consumer price index (CPI) inflation jumped from 2 percent to 6.7 percent (since 1967) with an acceleration to an average of nearly 9 percent since 1973 and over 13 percent in 1979.

The Standard and Poor's index of common stock prices, an indicator of both after-tax profitability and investors' expectations about the future of the economy, rose sixfold between 1949 and 1969. Even after adjusting for the rise in the general consumer price level, this index of share prices increased by more than 300 percent. In the decade since 1969, however, the index rose only 10 percent and in constant dollars fell nearly 50 percent. The poor performance of the economy in recent years can also be seen at a less aggregate level: a falling share of national income devoted to net investment and to research and development; increasing pressures and risks in the financial sector; low profitability and an aging stock of plant and equipment in many specific industries; and a deteriorating performance of United States exports.

There is a strong temptation to regard the poor performance of the past decade as the beginning of a new long-term adverse trend for the American economy. It is, however, too early to know whether such an extrapolation is really warranted. Some of the poor record of the 1970s has undoubtedly been due to inappropriate macroeconomic policies adopted during the Vietnam War, to the change in the production policy of the OPEC cartel, and to other disturbances whose impacts will eventually fade away.

But the deteriorating performance of the economy may also have more fundamental causes that will not automatically recede.

Indeed, some of the sources of our performance may now be so deeply rooted in our social and political system that they cannot be eliminated even when the causes of the problem become better understood. It is clear that there is little hope of reversing the poor performance that has lasted for more than a decade unless the underlying causes are identified and changed. Many of the papers and comments in this volume point to the expanded role of government as a major reason, perhaps the major reason, for the deterioration of our economic performance:

The government's mismanagement of monetary and fiscal policy has contributed to the instability of aggregate output and to the rapid rise in inflation.

Government regulations are a principal cause of lower productivity growth and of the decline in research and development.

The growth of government income-transfer programs has exacerbated the instability of family life and perhaps the decline in the birthrate.

The low rate of saving and the slow growth of the capital stock reflect tax rules, macroeconomic policies, and the growth of social insurance programs.

The expanded role of government has undoubtedly been the most important change in the structure of the American economy in the post-war period. The extent to which this major change in structure has been the cause of the major decline in performance cannot be easily assessed. This introductory essay is certainly not the place to evaluate just how much of our recent problem derives from specific government policies or to assess the positive contributions that government policies have made during the postwar period.

Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that government policies do deserve substantial blame for the adverse experience of the past decade. I would like, therefore, to devote these few pages to examining the general character of government policies and of government decision-making that causes it to create problems of the type we have experienced.

Economists generally regard all economic choices as the result of explicit comparisons of costs and benefits. When an individual buys an apple rather than a pear, we assume that he has considered the prices of each and the pleasures that he would expect from the apple and the pear. Even for more complex choices with uncertain future benefits, such as an individual's choice among careers or a firm's choice among investment options, the economist automatically assumes that the deci- sion-maker has considered the possible costs and benefits of the option he selects. Individuals and firms may occasionally be surprised by ad- verse consequences they had not anticipated, but on average the outcomes should correspond to expectations.

Applying such a "rational choice" view to government policies would imply that successive governments made deliberate decisions to accept certain adverse consequences in order to achieve other goals: for example, that the current high inflation was accepted in order to avoid more unemployment; that the low rates of saving and investment were accepted in order to have tax policies and transfer programs that could more equally distribute disposable income; or that the low rate of R&D spending and the fall in productivity were accepted as a consequence of imposing regulations that could protect the environment and the safety of workers.

I find this picture of economically rational choice implausible. I find it much more believable that the adverse consequences of government policies have been largely the unintended and unexpected by-products of well-meaning policies that were adopted without looking beyond their immediate purpose or understanding the magnitudes of their adverse long-run consequences:

Expansionary monetary and fiscal policies were adopted throughout the past fifteen years in the hope of lowering the unemployment rate but without anticipating the higher inflation rate that would eventually follow.

High tax rates on investment income were enacted and the social security retirement benefits were increased without considering the subsequent impact on investment and saving.

Regulations were imposed to protect health and safety without evaluating the reduction in productivity that would result or the effect of an uncertain regulatory future on long-term R&D activities.

Similarly, I believe the government never considered that raising the amount and duration of unemployment benefits to the current high levels to avoid hardship among the unemployed would encourage layoffs and discourage reemployment;

that Medicare and Medicaid, introduced to help the elderly and the poor, might lead to an explosion in health care costs;

that welfare programs, introduced and expanded to help poor families, might weaken family structures;

or that federal aid through the tax laws and through special credit programs to encourage homeownership would have such adverse effects on the cities, precipitating the relocation of business and consequent poverty and other problems for those who remained behind.

The list of well-meaning policies with unintended adverse consequences could be extended almost without limit.

Moreover, in many cases the adverse consequences have resulted not from the introduction of fundamentally new programs and policies, but from the fact that old programs are retained and expanded in a changed economic environment. Social security and unemployment compensation were introduced in the 1930s; the differences between the economy then and now would imply corresponding differences in the likely impact of these programs. The high rate of unemployment, the lack of investment demand, and the low rate of personal income tax constituted an environment in the 1930s in which the side effects of social security and unemployment compensation would be relatively innocuous. Today's tight labor market, capital scarcity, and high personal tax rates imply that these programs now impede employment and capital formation.

Similarly, our personal and business tax laws were designed for an economy with little or no inflation. The interaction of this tax structure with the current high inflation rates causes extremely high effective tax rates on capital income, a discouragement to saving, and a distortion of investment away from plant and equipment toward housing and consumer durables.

Unfortunately, even when the inappropriateness of old policies is recognized, change is difficult to achieve. Existing programs are maintained even though the same programs would not be adopted today. These programs survive and grow with the help of sympathetic bureaucrats and well-organized beneficiary groups. Loyalties develop to the form of public programs rather than to their basic purpose.

There is a fundamental reason why well-intentioned government policies often have adverse consequences. The government in its decision-making is inherently myopic, more myopic than either households or firms. Political accountability means that a policy will be judged on its apparent effects within as little as two years. A congressman or senator may understand the long-run implications of a policy, but the relevance to him of those long-run effects is very limited if voters look only at the short-run impact. The political process lacks the equivalent of capital assets through which private decision-makers are rewarded or penalized for the long-term consequences of previous decisions. And because the political process does not reward or punish elected officials for the long-term consequences of their actions, there is little or no incentive for these officials to learn about such long-term effects.

Political myopia reflects the public's general inability to anticipate the long-run consequences of political decisions and even to associate those consequences when they occur with the policies that caused them. It is not surprising therefore that well-meaning policies frequently have unexpected adverse consequences and that policies with short-run costs and long-run benefits are not adopted.

The nature of the political decision-making process is perhaps most apparent in the development of macroeconomic policy. In the early 1960s, expansionary monetary and fiscal policies were pursued in what might be described as a rational choice based on the Phillips curve analysis that was then widely accepted by the economics profession. But later in the decade President Lyndon Johnson rejected the warnings of his economic advisors that taxes had to be raised in order to avoid an accelerating rate of inflation. Johnson chose to accept an increased long-run inflation rate in order to avoid the short-run political cost of a tax increase. His choice, while perhaps politically rational, was economically myopic.

During the 1970s, the government and the monetary authorities focused on the short-run goal of reducing unemployment through expansionary policies that served only to exacerbate the inflationary situation. If escaping from the current high rate of inflation requires a sustained period of increased unemployment and economic slack, the shortsighted- ness of the political process may make this very difficult to achieve.

The myopia of the political process is also reflected in policies that discriminate against saving and investment. It is significant that pro- investment legislation has always been justified as a way of stimulating short-run demand and thereby reducing current unemployment. There has been little effective support for policies to increase saving and investment in order to expand the capital stock and raise future income. In contrast, tax and transfer policies that favor current public and private consumption have been favored. The long-run benefits of increasing the capital stock apparently lie beyond the political horizon.

If the electoral process makes political decisions inherently myopic, we should recognize this as an intrinsic feature of our democracy. It is important, moreover, to consider this bias in political decision-making in determining the extent of the role that government should play in our economic life.

Of course, politicians do not have a monopoly on myopia. But although some of the political shortsightedness is undoubtedly a response to constituent pressures, the myopia of the political process actually encourages voters to be impatient. Voters demand faster results from the political process than they demand from private activities because they recognize that elected officials are accountable only in the short run. Politicians' promises of "quick-fix" solutions to major social and economic problems also induce voters to expect such solutions and to judge incumbents and candidates by a short-run standard.

The policies that are adopted also bias individuals to be more short-sighted and impatient in their private decisions. Tax policies, credit market rules, and social insurance programs encourage current consumption and a decrease in private provisions for the future. In more subtle ways, government programs that substitute the state for the family cause behavior that weakens the development of the future population: fewer births, more unmarried individuals, more childless couples, and more divorced parents. Of course, to some extent, these government policies may only reflect a growing impatience in the public that stems from other sources. It is impossible to identify the relative importance of different factors, but the government clearly bears substantial responsibility for encouraging and stimulating shortsighted behavior.

To the extent that the poor economic performance of the past decade can be traced to the growing role of government and the inherent myopia of the political process, improvement of our performance will be difficult to achieve. Difficult but not impossible. The public's support for environmental protection and for expenditure on research and development shows that programs with long-run benefits can be politically viable. There are at present some signs of growing public and governmental interest in increasing the rate of capital formation. The Keynesian fear of saving that has dominated thinking on this subject for more than thirty years is finally giving way to a concern about the low rates of productivity increase and of investment. The public has also recognized that the key problem for macroeconomic policy is now inflation, not unemployment. If the public begins to see more clearly the links between current policies and future consequences, there will be less reason to fear the unexpected consequences of myopic decisions.

The 1970s have been a decade of frustrated expectations. The size and influence of the government have grown rapidly, but the public's distrust of government has grown even more rapidly. The economics profession has discovered a new humility as the economy's performance has worsened. As the 1980s begin, there is widespread anxiety about the future. Will this decade be a period of severe economic problems with a major recession, accelerating inflation, or both? Or can the poor economic performance of the 1970s be reversed?

The current data on the developing state of the economy are not clear. And, while some events may be outside our control, the success of the economy in the current decade and in the remainder of this century will depend also on whether we choose wisely as we reevaluate and restructure our major economic policies.

LINK: <http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11294>

All in all a pretty superficial analysis. Essentially NO argument beyond assertion that social transfers create problems. Surprisingly, he does not even mention structural deficits or the Nixon price controls. That regulation not guided by cost-benefit analysis is a drag on growth is plausible, but unquantified (and local NIMBY-ish, professional licensing, etc. regulations are probably much more damaging than national ones). The idea that unemployment insurance is so generous as to discourage employment is ludicrous; that Medicare is responsible for the employer "provided" health insurance disaster ridiculous. The criticism of monetary policy is correct if anachronistic; inflation targeting as the "prices" half of the Fed's mandate had not been invented. [The "inflation" criticism of Johnson for not increasing taxes to pay for Vietnam makes sense only if one presumes that the Feb accommodates fiscal deficits.]

It's not even "neo-liberal" -- use the market, where appropriate, to achieve growth with equity -- in my (Word Bank-ish) conception.

The poster boy for argumentum a fortiori. How could this have been influential? I’m not trying to be snarky. I really am curious how this sort of “reasoning” became so dominant. Certainly it’s easy to grasp, and easy to repeat. I’ve assumed that’s part of its appeal, especially for lazy yet aggressive people.