Slides for Tomorrow's (2025-02-24 Mo) "American Exceptionalism" American Economic History Lecture

Why isn't the United States of America one Giant Australia (or New Zealand)? Why the u.s. didn’t stay a land of farmers & miners. How infrastructure, immigration, scale, and not-stupid tariffs...

Why isn't the United States of America one Giant Australia (or New Zealand)? Why the u.s. didn’t stay a land of farmers & miners. How infrastructure, immigration, scale, and not-stupid tariffs built an economic superpower…

The Road Taken: How America Chose Hamilton Over Jefferson

The Natural Path: A Primary Product-Focused Economy

Standard economic logic—the principle of comparative advantage—would have, starting in 1789, pushed the settlement-conquest economy of the United States, so abundant in land and natural resources, to a comparative and competitive advantage as the world’s largest and most productive primary product-exporting economy. The basic intuition is straightforward: a country with an abundance of a particular resource is pushed by very powerful incentives to specialize in producing and exporting those goods which it can make with its relatively most abundant and hence relatively lowest=price resources, while importing that require resources it relatively lacks. The newborn United States, starting in the wake of the plagues that had devastated the First Nations of America and believing that God had called it to a Manifest Destiny to conquer and settle a continent, had a massive land frontier, rich soils, and extensive mineral deposits It was scarce in labor. It was scarcer in capital and in technologists. Those factors all pushed toward a comparative-advantage configuation in which it would have become the natural supplier of foodstuffs, cotton, timber, and metals to the industrializing economies of northwest Europe.

Indeed, there were very powerful—indeed, for most of the period before the Civil War, dominant—political and cultural forces also pushing America toward the development path of its initial-conditions comparative-advantage configuration. Farming, exporting, and rurality as the suitable and meet occupations for a free people is an idea associated with Thomas Jefferson and his political heirs. Commerce and industry and urbanity as a package is an idea associated with Alexander Hamilton and his political heirs. There is a giant Jefferson Memorial in Washington DC, on the Tidal Basin surrounded by cherry trees. There is no giant Hamilton Memorial.

Under this—natural—model, the U.S. would have exported raw materials while importing finished goods, much like Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand did. (Canada followed the U.S. pattern, as Ontario became part of the U.S. Midwestern industrial economy.). This economic trajectory would have created a wealthy agrarian society—with possibly a small élite of truly plutocratic resource barons—and sustained a relatively high-wage labor market due to land abundance. It would have delivered prosperity. But the prosperity would have been one with a relatively simple economic structure, without high complexity or deep industrialization. Moreover, once the best farmland was occupied and the mechanized tapping of the richest mineral deposits exhausted, population growth would likely have slowed. The primary-product-based economy would have lacked the ability to sustain large-scale urbanization, and hence there would have been no obvious reason for the huge flow of immigrants the historical U.S. attracted to come to an America where there was much less opportunity on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, in Southie in Boston, or on Taylor Street in Chicago,

The “Jeffersonian” Primary Product Trap(s)

Economic history teaches us that this particular comparative-advantage path carries substantial risks, in terms of wealth distribution, its long-term economic resilience, and its long-term economic growth. Specializing in primary products places an economy in a precarious position for several reasons:

Inelastic Demand and the Distribution of Technological Gains

When a country specializes in manufacturing, productivity gains from technological improvements tend to benefit producers, as demand for manufactured goods is more elastic—more and better cars, appliances, and electronics create new consumer markets. But for primary products, demand tends to be inelastic: people do not consume dramatically more wheat or iron ore just because production becomes more efficient. Instead, productivity gains drive down prices, disproportionately benefiting consumers and reducing the profits of producers. This means that while technological advances in manufacturing translate into wealth accumulation for the manufacturing country, advances in agricultural and mineral extraction often predominantly benefit the industrial consumers elsewhere rather than the raw material exporters.Economic Simplicity and the Fragility of the Division of Labor

A primary-product-focused economy remains structurally simple. Unlike manufacturing, which develops extensive networks of suppliers, engineers, financiers, and skilled workers, primary product economies tend to cluster around a few major exports. This concentration makes the economy vulnerable to global demand shifts and price volatility. The result is a fragile economic structure, unable to sustain a broad division of labor and ill-prepared for the shocks of deglobalization.The Engineering Externality: Innovation Happens Where Engineers Are

Industrial economies create communities of technological expertise—engineers, machinists, and scientists who work together in innovation hubs. These hubs generate vast knowledge spillovers that accelerate productivity growth. In contrast, primary-product economies merely adopt external innovations rather than generating them. By failing to cultivate homegrown technological expertise, primary-product economies miss out on long-term economic dynamism.

Given these disadvantages, remaining a raw material supplier to industrial Europe would have constrained American economic potential, leaving it structurally dependent on global markets for growth and innovation.

The “Hamiltonian” Turn: How America Chose Industrialization

Yet, the United States did not remain trapped in this trajectory. Instead, it embarked on a radically different path—one that prioritized technological, industrial, and educational investments. This divergence was neither inevitable nor automatic; it was the product of deliberate policy choices, political battles, and historical contingencies:

Alexander Hamilton’s Vision

One of the most consequential early voices for an industrialized America was Alexander Hamilton. In his 1791 Report on Manufactures, Hamilton argued that economic independence required a strong manufacturing sector. He proposed protective tariffs, government subsidies for industry, and infrastructure investments to nurture domestic production. His vision countered the Jeffersonian ideal of an agrarian republic, which saw manufacturing as a source of corruption and dependency.Tariff Protection and Industrial Policy

Throughout the 19th century, the U.S. government actively protected nascent industries through high tariffs on imported goods, ensuring that domestic manufacturers could develop without being crushed by foreign competition. By the late 19th century, this protectionist approach had nurtured a robust industrial base, allowing American manufacturers to compete on the global stage.The American System of Manufacturing

By the mid-19th century, American manufacturing had adopted key innovations—interchangeable parts, mass production techniques, and labor-saving machinery—that gave it a distinct competitive edge. Innovations such as the McCormick reaper in agriculture and the mechanization of textile and firearm production helped industrialization spread beyond traditional centers.Infrastructure and Scale

The U.S. federal and state governments invested heavily in infrastructure—canals, railroads, and later highways—facilitating the movement of goods and labor. This infrastructure expansion helped integrate the national economy, creating economies of scale that reinforced industrial growth.Education and Human Capital

Unlike Britain or continental Europe, the U.S. prioritized mass education early on, ensuring a literate workforce. The land-grant university system, established in the mid-19th century, played a crucial role in training engineers and scientists, further enhancing technological capabilities.Mass Immigration and Workforce Development

The United States became a magnet for skilled and unskilled labor, drawing millions of immigrants who contributed to its industrial workforce. Unlike Australia or Argentina, which had similar resource endowments but smaller labor pools, America’s massive immigration waves allowed it to scale up industrial production rapidly.World War II and the Birth of the Military-Industrial Complex

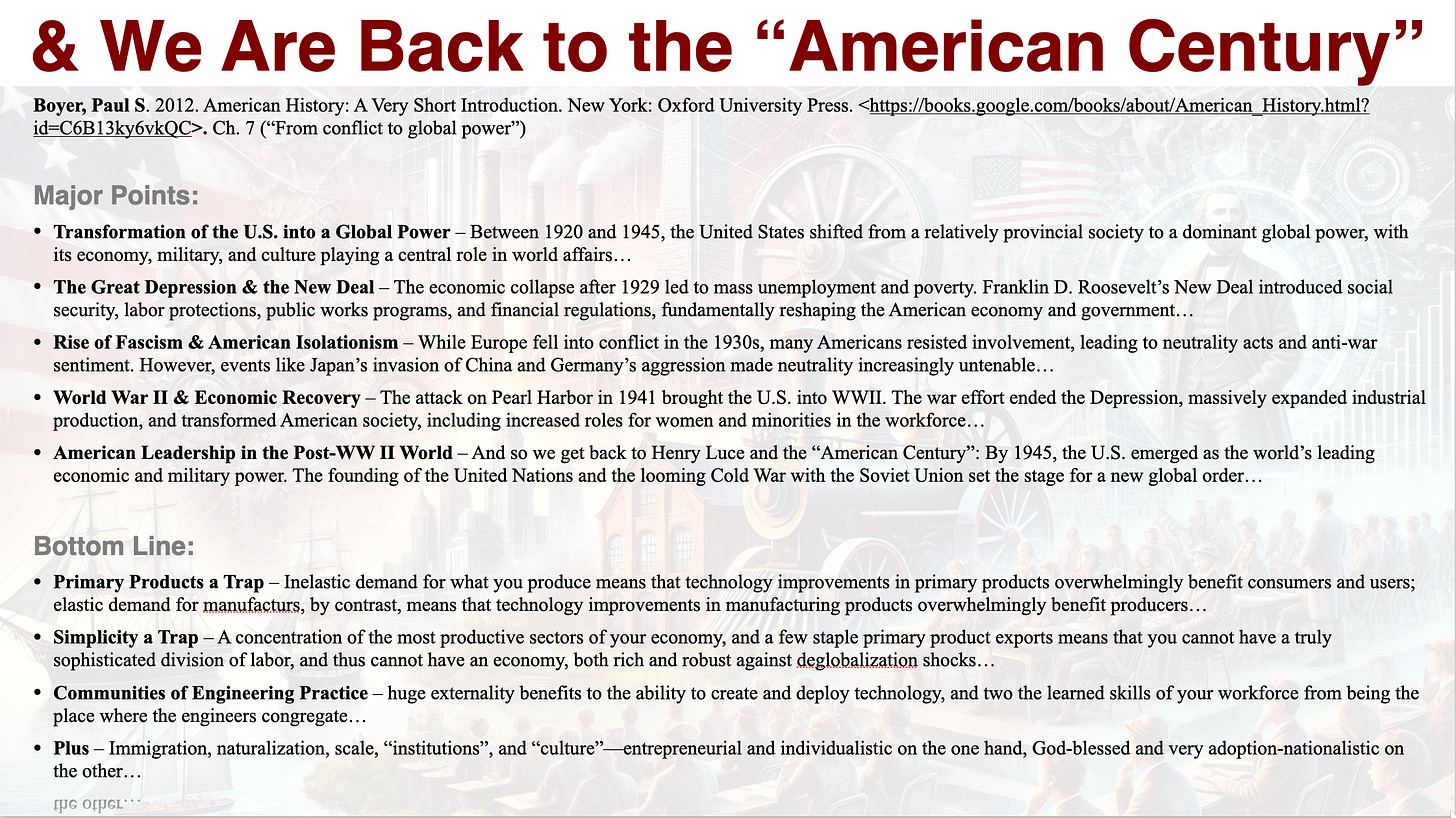

The final push that cemented America’s industrial supremacy was World War II. The war effort required massive production, leading to technological breakthroughs in aviation, computing, and materials science. The postwar order, shaped by American dominance, further reinforced its industrial strength.

Conclusion: The “Unnatural Path” That Became Destiny

Economic logic initially suggested that America would follow a natural resource-exporting model, much like Australia or Argentina. But thanks to strategic policy interventions—infrastructure investments, industrial subsidies, educational investments, and not-stupid tariffs—America shifted toward an industrial model that unlocked higher long-term growth.

The key lesson is that primary-product economies face structural disadvantages that limit their ability to control their own destinies. By choosing the path of manufacturing, innovation, and technological leadership, America not only escaped the primary-product trap but also positioned itself as the dominant economy of the 20th century.

Hamilton, it turns out, had the last laugh over Jefferson.

But how, exactly, did this reversal of fortune come to be?

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…

I think there is lot to the Hamiltonian development strategy.

But I would not underestimate the sheer fertility of the US compared to Australia, at least relative to European agriculture and livestock raising methods.

There is nothing like a Midwest/Mississippi Basin in Australia and as a result the USA can and did support a vastly larger population. The role of the Mississippi (and the Erie Canal) in opening up the Midwest to agricultural and commercial development before the railroad should not be underestimated.

This allowed the US to develop a very sizeable internal demand for manufactured goods which, together with the Hamiltonian tariff policy, allowed manufacturing to flourish.

The US population had exceeded that of the UK already by 1860 (roughly 31 million). In 1860 Australia had only 1.17 M, comparable to the 13 colonies in 1740. Even today Australia only has 27 M or so, dwarfed by most of its trading partners (even the physically much smaller Japan has 124 M)

Australia did not become independent from the UK until 1900 and even after that remained within a privileged economic/strategic commonwealth trade bloc (unlike Argentina).

Thus, I would suggest that geography as well as trade policy had a lot to do with the exceptionalism of the US development path.

It would never have worked for Australia, South Africa, Canada or Argentina. Even today Australia has a negligible manufacturing sector.

So maybe we have to give some credit to Jefferson for the Louisiana purchase!

Interesting read. I'd like an analysis of where we'd be if we kept the taxation levels as they were prior to Reagan.