Slouching Tweetstorm:

My tweet storm for Slouching Towards Utopia:

What I call the “long twentieth century” started with the watershed-boundary crossing events of around 1870—the triple emergence of globalization, the industrial research lab, and the modern corporation—which ushered in changes that began to pull the world out of the dire poverty that had been humanity’s lot for the previous ten thousand years. What I call the “long twentieth century” ended in 2010, with the world’s leading economic edge, the countries of the North Atlantic, still reeling from the Great Recession that had begun in 2008, and thereafter unable to resume economic growth at anything near the average pace that had been the rule since 1870. The years following 2010 were to bring large system-destabilizing waves of political and cultural anger from masses of citizens, all upset in different ways and for different reasons at the failure of the system of the twentieth century to work for them as they thought that it should.

In between 1870 and 2010, things were marvelous and terrible, but by the standards of all of the rest of human history much more marvelous than terrible.

There we have my first claim about the history of the long 20th century: that, both compared to all past centuries and on an absolute scale, the history of the long 20th century was indeed, as Eric Hobsbawm says, the history of an Age of Extremes—but those extremes were much much much more marvelous than terrible. The arc of long 20th-century history was, by and large and broadly, with many hesitations, backward slippages, and complications, toward not justice but at least toward hope, hope for someday a truly human world.

The one-hundred and forty years 1870-2010 of the long twentieth century were, I strongly believe, the most consequential years of all humanity’s centuries.

Here is my second claim: that the long 20th century was the most consequential century in humanity’s history, ever. Why? Because back in 1870 humanity was still desperately poor. Now some of us are very rich—the upper-middle classes of the global north are rich beyond the most fabulous dreams of luxury dreamed by previous ages. And most of us are, by the standards of all previous centuries, very comfortable and long-lived indeed. And that all of us are not so is a great scandal.

And it was the first century in which the most important historical thread was what anyone would call the economic one, for it was the century that saw us end our near-universal dire material poverty.

Here is my third claim: That in the long 20th century, for the very first time in human history, the principal axis of history was economic—rather than cultural, ideological, religious, political, military-imperial, or what have you. Why was the long 20th century the first such century in which history was predominantly economic? Because before 1870 the economy was changing only slowly, too slowly for people's lives at the end of a century to be that materially different from how they had been at the beginning. So the economy was thus the painted-scene backdrop behind the stage, rather than the action on the stage. (Now do note that you can still say that the principal axis of any millennium's history is economic, for over millennia things do change.)

But back up: what I have said here simply establishes that the principal axis of the history of the long 20th century could have been economic—that the economy was changing and that enough economic damn things were happening one after the other to make it a player in history. But was it a lead actor? One of the major themes of my book is going to be: Yes, it was the lead actor.

My strong belief that history should focus on the long twentieth century stands in contrast to what others—most notably the Marxist British historian Eric Hobsbawm—have focused on and called the ‘short twentieth century’, which lasted from the start of World War I in 1914 to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

This is a minor digression: My Grand Narrative of the 20th century is not the only Grand Narrative one could construct. We have to have some Grand Narrative, some single most-important plot thread—if we don't, we almost cannot think at all, for we really have almost no way to think other than in narrative. I think mine is the most important. But others disagree. And it is important never to forget that every Grand Narrative allows and enables you to see some things—hopefully the most important things to you—very clearly indeed, but blocks your vision of other things.

Such others tend to see the nineteenth century as the long rise of democracy and capitalism, from 1776 to 1914, and the short twentieth century as one in which really-existing socialism and fascism shake the world.

In fact, I believe that, in the western academy, the predominant major Grand Narrative, at least implicitly, of the 20th century is that it was really-existing socialism vs. fascism, and really-existing socialism knocking itself out in the process of winning its victory, leaving consumer capitalism—“that old bitch gone in the teeth”, as the other great post-WWII British Marxist historian E.P. Thompson calls it <https://marxists.org/archive/thompson-ep/1973/kolakowski.htm…>, as the unworthy victor in the struggle over systems of political-economic organization.

Needless to say, I do not take this view.

I see the three-part mid-century struggle between the systems as, not a sideshow, but as something taking place outside of the center ring.

Histories of centuries, long or short, are by definition grand narrative histories, built to tell the author’s desired story.

You cannot write a history of an entire century without committing yourself to some Grand Narrative—without a spearpoint you cannot conduct a successful hunt, and without a central thread for them to follow, humans, who think in narratives, cannot grasp and remember your story. Thus the necessity of the spearpoint. It will be imperfect and "false". But it is necessary and essential. You have to hold both the necessity and the imperfectness in your mind simultaneously, always, as you read and think. The map is not the territory. The map, however, is the map. Your history will then stand or fall based on how well you back that narrative.

Setting these years, 1914–1991, apart as a century makes it easy for Hobsbawm to tell the story he wants to tell.

Hobsbawm’s choice of period was calculated to provide heavy weight for the spearshaft behind the spearpoint of the particular Grand Narrative he wished to tell. Indeed, if you start and end on Hobsbawm’s dates—1917 and 1990—it is very hard not to wind up telling some version of his story. It may well not have the valence he gives it: of World Communism as the tragic and doomed hero of the century, defeating fascism but being so poisoned by the circumstances of its development and struggle that it then expires after a long decline, leaving its unworthy rival consumer capitalism in control, and thus closing off humanity's road to utopia. The 1917-1990 short 20th century can be told with Frank Fukuyama's "end of history" valence instead. But, as I said, while that is certainly a story, I do not think it is THE story that people 500 or 1000 years from now will .think is important and tell when they tell the story of the years on both sides of 1950.

But it does so at the price of missing much of what I strongly believe is the bigger, more important story.

I really don’t think either really-existing socialism or fascism is, in the long run of human destiny, worthy of being a protagonist (or an antagonist) in big-think broad-sweep history. I mean: really-existing socialism was a dead end, a false path, a horrible warning in terms of political-economic systems. And as for fascism... well... .if it turns out that future historians want to tell political history not as a whig progressive but rather as an Aristotelian alternation-and-decay-and-replacement-of-régimes story, then fascism will have its place as a form of tyranny in the age of mass and social media, much as Thoukidides discusses the role of Peisistratos and his supposed championing of the cause of the hyperakrioi—with the exception that Peisistratos did actually have policies to boost the prosperity of the hyperakrioi, and did make Athens great again. But if we do better than Aristotelian alternation in political régimes in the long run, fascism and its cousins will also be seen as dead ends, horrible warnings, stories that we tell to remind us how horrible people can be to one another, rather than the protagonist of some Grand Narrative principal thread of human history.

The bigger, more important story is the one that runs from about 1870 to 2010, from humanity’s circa-1870 success in unlocking the gate that had kept it in dire poverty, up to its circa-2010 failure to maintain the pace of the rapid upward trajectory in human wealth that the earlier success had set in motion.

I think that is the worthy story of the history of the 20th century has as its protagonist neither really-existing socialism, nor really the “free world” that triumphed over the totalitarianisms. I think that the worthy story is, rather, humanity’s escape from Malthusian poverty—and from societies in which the class of people with leisure to think deeply and nutrition to think about something other .than how hungry they are is small, and is composed of those who have figured out how to unproductively take an outsized share by force and fraud. This escape from the realm of material necessity into the realm of freedom, choice, and options is, I think, the proper story—and the big story. And its proper protagonist is humanity.

What follows is my grand narrative, my version of what is the most important story to tell of the history of the twentieth century. It is a primarily economic story.

Now I start to say exactly what my Grand Narrative thread that I will use to organize the history of 1870-2010 is.

It naturally starts in 1870.

A short reminder to readers of the start date.

I believe it naturally stops in 2010.

A short sentence to remind readers of the end date.

As the genius Dr. Jekyll-like Austro-English-Chicagoan moral philosopher Friedrich August von Hayek observed, the market economy crowdsources—incentivizes and coordinates at thegrassroots—solutions to the problems it sets…

Introducing two supporting characters: the market economy with its extraordinary power to grassroots-crowdsource powerful solutions to the problems it is set, and its principal 20th century theoretician, the good Dr. Jekyll-side of Prof. Dr. Friedrich August von Hayek.

Back before 1870 humanity, given its population, did not have the technologies or the organizations to allow a marketeconomy to pose the problem of how to make humanity rich.

However, back before 1870 humanity did not have the technologies—either the technologies of manipulating nature or the technologies of organizing humans—in either the level amount or the rate of growth for the market economy to be set the problem of moving humanity out of the realm of necessity in which it was trapped, the realm of dire Malthusian poverty.

So even though humanity had had market economies, or at least market sectors within its economies, for thousands of years before 1870, all that markets could do was to find customers for producers of luxuries and conveniences, and make the lives of the rich luxurious and of the middle class convenient and comfortable.

Hence before 1870 market sectors, and market economies, had merely turned their crowd-sourcing energies to making luxurious for the rich and conveniences to make the (small) middle-class comfortable. (Remember! The “middle class” is not the median 50th percentile! The “middle class” are, in previous centuries, those who are not rich but who do not fear starvation should the Wheel of Fortune take even a minor adverse turn!)

Things changed starting around 1870.

Another short sentence for the sake of rhetoric, attempting to hammer into readers the idea that 1870 and its triple—the coming of globalization, of the industrial research lab, and the modern corporation—in a strong and powerful sense marked the end of all previous human history.

Then [in 1870] we got the institutions for organization and research and the technologies—we got full globalization, the industrial research laboratory, and the modern corporation.

The coming of all three of these more or less at once was a truly mighty change. It rationalized and routinized the discovery and development and the development and deployment and not just the local but the global deployment of technological advances. The coming of all these three more than quadrupled the pace at which humanity’s technological empire was increasing. And that step-up in the growth rate lasted from 1870 to 2010.

Were those three changes baked in the cake by what had come before? Are they best thought of as slow, evolutionary advances that one would naturally have expected to follow from the course of the Industrial Revolution up to 1870? Alfred D. Chandler says: probably not. His "Scale and Scope" makes powerful arguments that the creativity that produced the modern corporation, and the industrial research labs that served it, were results of the particular historical situation and of accidents that happened in the U.S. after the Civil War, After all, no similar developments took place in France or Britain.

I tend to see industry-oriented universal banks as a key intermediary: those emerged in the U.S. and in Germany, so it was not a unique event. But they did not emerge elsewhere. So it was a rare event. This, however, carries me far away from my main thread.

These were the keys.

Again: a very short sentence to rhetorically hammer home the point that this 1870 triple of the industrial research lab, the modern corporation, and full (not just fledgling) globalization was really really important.

These unlocked the gate that had previously kept humanity in dire poverty.

Another short sentence, driving home the point. Without this triple of industrial research lab, modern corporation, and full globalization, we might well have been doomed. We might well have been doomed by slow productivity growth, by our fecundity, and by the patriarchy that made becoming the mother of at least one son who survived to adulthood nearly the.only source of significant social power for female members of homo sapiens sapiens—to Malthusian or near-Malthusian poverty.

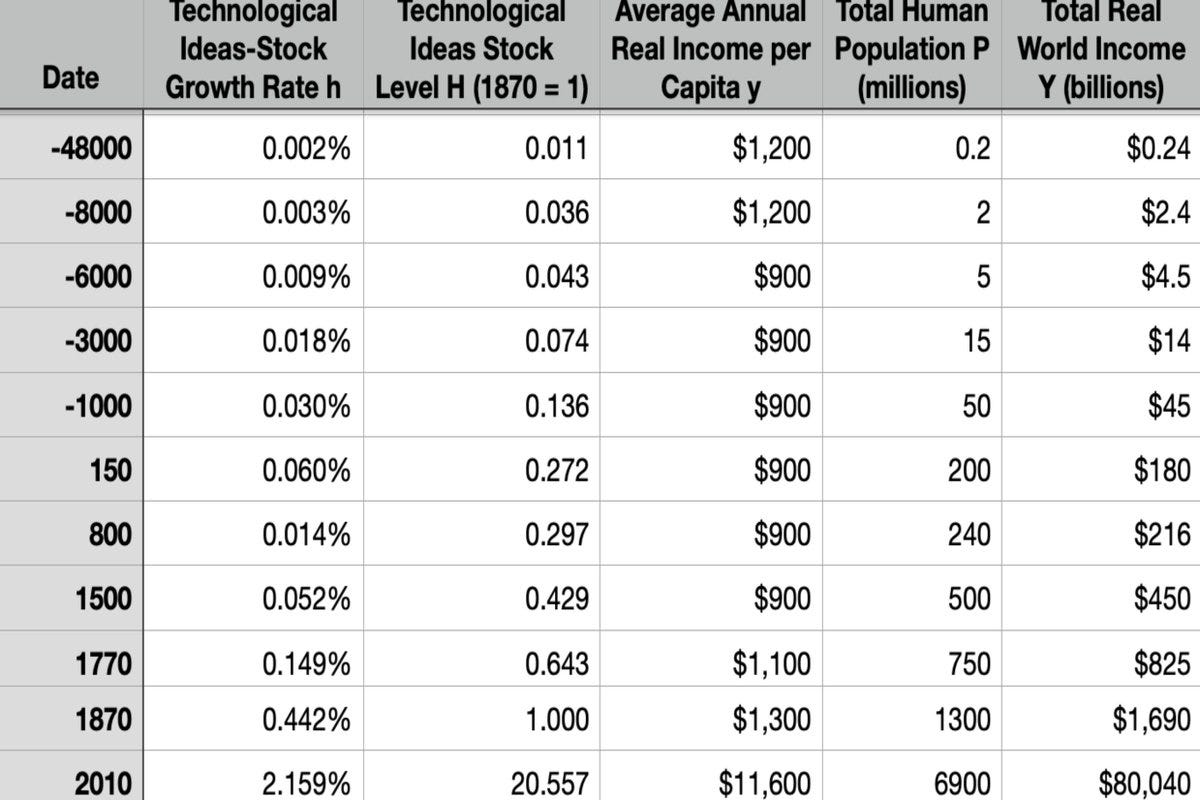

(Parenthetically, many would dismiss my focus on 1870 and the industrial research lab, modern corporation, full globalization triple. They would say that the emergence of something like our modern world was close to baked in the cake once we had steampower and textile machinery. But is that really true? The First Industrial Revolution depends on really really cheap coal, and by 1870 the really, really cheap coal was near its end. Worldwide, the pace of global technological progress deployed was only some 0.45%/year on average from 1770-1870, less than 1/4 of what it was going to be from 1870-2010. If that pace had slowed to 0.3%/year (or even stayed ..at 0.45%/year), population growth of 0.6%/year (or 0.9%/year) would have induced sufficient resource scarcity to counterbalance technology's boost to living standards, and leave the bulk of humanity still under near-Malthusian conditions. Without the triple, I think, we might well today have a world in which the rough technology level would be roughly that of 1895 with 5 billion people on the globe: a steampunk world indeed.)

These unlocked the gate that had previously kept humanity in dire poverty…

Without this triple, we had been doomed—by slow productivity growth, by our fecundity, and by the patriarchy that made becoming the mother of at least one son who survived to adulthood nearly the only source of significant social power for female members of homo sapiens sapiens—to Malthusian or near-Malthusian poverty. With this triple, and with the more-than-quadrupling of the pace of proportional growth of humanity's deployed technological prowess that it drove, we had the possibility of escape, into a realm where we could for the first time build a truly human world.

The problem of making humanity rich could now be posed to the market economy, because it now had a solution.

The extraordinary more-than-quadrupling of the pace of human .technological progress deployed into the world economy allowed the market to turn its energies to doing more than making the lives of the rich luxurious and providing conveniences for the middle class.

On the other side of the gate, the trail to utopia came into view.

It was Malthusian poverty that had kept humanity from building its utopia or utopias before 1870. But with the coming of the rapid 2% per year technological progress of modern economic growth, that blockage to sprinting or running or marching humanity to utopia was removed. With the deployed technological prowess in manipulating nature and organizing humans doubling every 35 years starting in 1870, humanity's problem was merely to decide, deliberately, consensually, and thoughtfully, which utopia or utopias we should build for our descendants, right? right?

And everything else good should have followed from that.

Over the long 20th century humanity really should have used our collective technological prowess to build a Utopia or Utopias–have created, as my friend Max Singer used to say, a truly human world. Spoiler: it did not do so. But why not? And is there anything we can do to do better in the 21st century? And, if so, what?

Much good did follow from that.

Another short sentence to drive home the idea that while the long 20th century was both marvelous and terrible, it was more marvelous than terrible. Indeed, it was the fact that so much of it was so marvelous that makes it so disappointing that we have not progressed further on the road to utopia, to a truly human world.

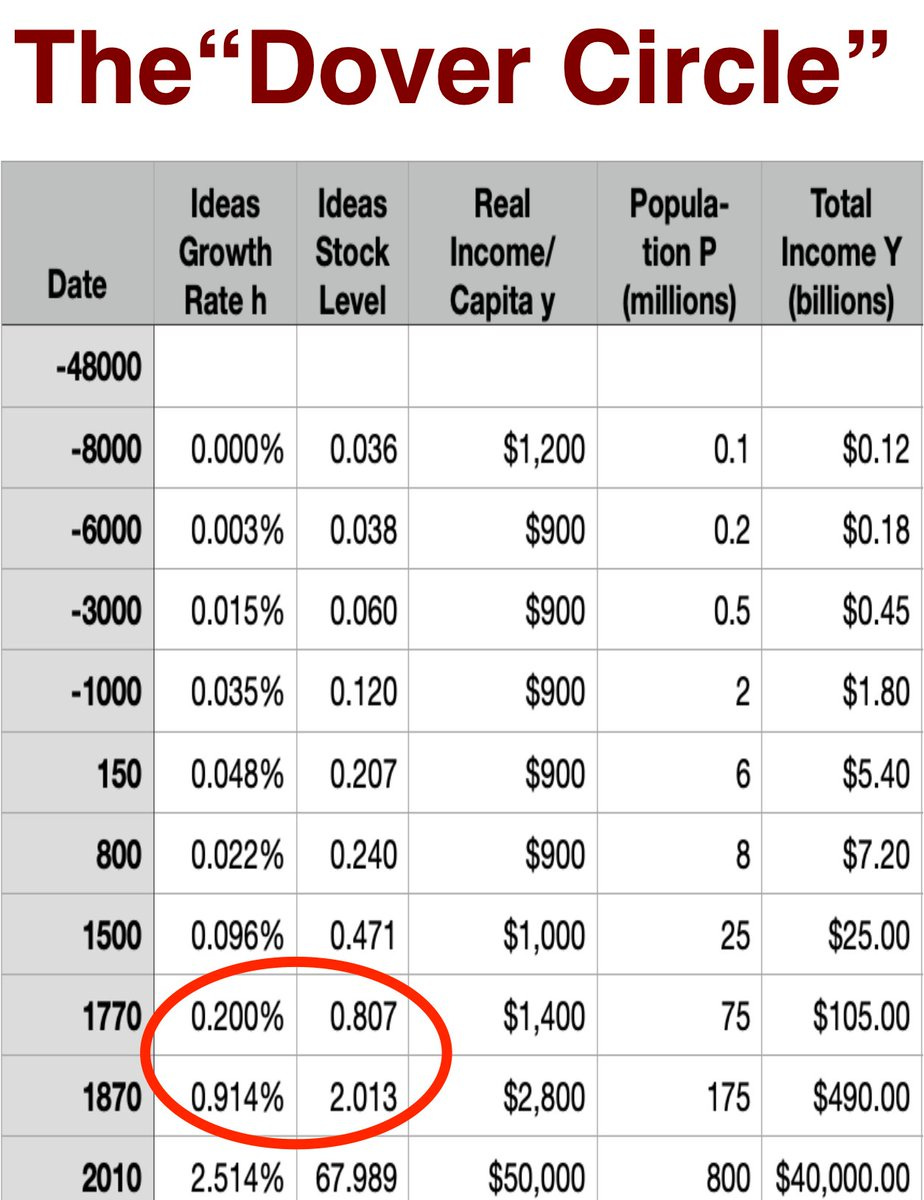

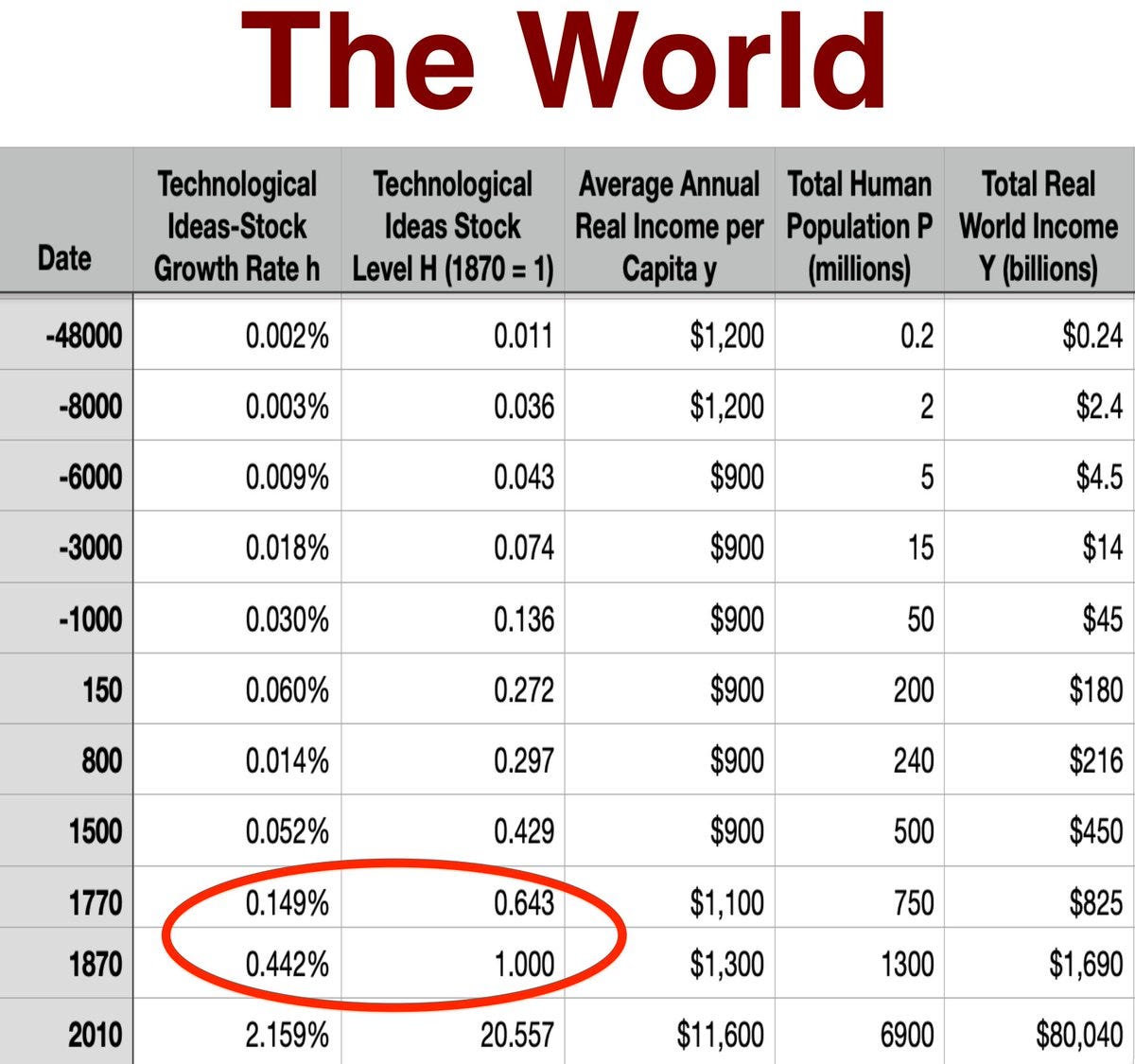

My estimate—or perhaps my very crude personal guess—of the average worldwide pace of what is at the core of humanity’s economic growth, the proportional rate of growth of my index of the value of the stock of useful ideas about manipulating nature and organizing humans that were discovered, developed, and deployed into the world economy, shot up from about 0.45 percent per year before 1870 to 2.1 percent per year afterward, truly a watershed-boundary crossing difference.

If there is one single nugget of insight that I want readers of my book to permanently engrave on their brains, this is it: around 1870 the rate of technological progress and thus of potential wealth creation went into much higher gear. After 1870, humanity's deployed technological capabilities and thus potential prosperity doubled every thirty-five years—and with it came economic creative destruction that reduced old economic structures to rubble and built new ones, and .did it again, and again, and again, every single generation. Before 1870? From 1770-1870 humanity's globally-deployed technological prowess had a doubling time of about 150 years—not 35. From 1500-1770 it had a doubling time of 500 years. And before 1500, we are looking at a doubling time of 2000 years. The difference between our world, in which technological progress creatively destroys and revolutionizes the economy every 35 years, and the world of Agrarian-Age antiquity in which the same proportional changes in technology and economy, and thus in polity and society, take not 35 but 2000 years is, I think, a master force shaping human history.

A 2.1 percent average growth for the 140 years from 1870 to 2010 is a multiplication by a factor of 21.5.

Just a very short sentence to hammer home the obvious to those who don't have exponential growth magnitudes in their immediate intellectual panoply: a more than tenfold amplification of human technological prowess in 140 years is a REALLY BIG F---ING DEAL. To get an equivalent proportional jump in the other direction, you have to go back from 1870 to the Bronze Age— to the year -2000 or so. We are, proportionately, as separate in technology from the railroad's Golden Spike and the first transoceanic cables as those were from the earliest chariots and the sculptor of the dancing girl of Mohenjo-Daro:

That [the 21.5-fold multiplication of human deployed technological prowess over 1870 to 2010] was very good: the growing power to produce and create wealth and earn an income allowed humans to have more of the good things, the necessities, conveniences, and luxuries of life, and to better provide for themselves and their families.

Briefly and very very roughly, what twenty workers were needed to do in 1870 with their eyes, fingers, thighs, brains, mouths, and ears, 1 worker was able to do in 2010. (And what one worker could do in 1870 required 20 in -6000; but the overwhelming bulk of the of the potential benefits for humansfrom that twentyfold -6000 to 1870 upward creep of technological knowledge had been eaten up by growing resource scarcity: the land and other natural resources available to support 1 person in -6000 had to support 200 by 1870.) But the twentyfold post-1870 technological-progress wave had to deal not with a 200- but only a 6-fold multiplication of human numbers, leaving lots to be devoted to bringing about much higher average productivity.

This does not mean that humanity in 2010 was 21.5 times as rich in material-welfare terms as it had been in 1870: there were six times as many people in 2010 as there were in 1870, and the resulting increase in resource scarcity would take away from human living standards and labor-productivity levels.

The unprecedented multiplication of human technological prowess and thus potential productivity over 1870-2010 was accompanied by unprecedented growth in population as well: the population explosion, now near its end with the near-completion of the demographic transition. Some of the 21-fold amplification of technology had to go to compensate for the six-fold multiplication of human population, from 1.3 to 7.6 billion, over 1870-2010. With much less land available to grow food for your typical person and other forms of resource scarcity, average growth in productivity and living standards could not keep pace with technology. But technology did definitively win the race with population: the Malthusian Devil that had kept humanity poor for millennia was trapped inside the confining pentagram.

As a rough guess, average world income per capita in 2010 would be 8.8 times what it was in 1870, meaning an average income per capita in 2010 of perhaps $11,000 per year (to get the figure of 8.8, you divide 21.5 by the square-root of 6; or, rather, we multiplied 8.8 by the square-root of 6).

Let me hasten to remind you that these are extremely rough guesses that only a foolhardy idiot would commit himself to. Only a foolhardy idiot would dare assert that productivity in living standards in the world of 2010 were 8.8 times what they had been in 1870. Such a number requires adding and then dividing things that really cannot properly be added and divided in any sense. The guess that world population in 20210 was six-fold higher than it had been in 1870 is at least a guess that we can more-or-less justify. But the further steps—that there is a one-dimensional thing we can call "technology discovered, invented, developed, deployed, and diffused" and that if we normalize it to our income measure the right way to compensate for population growth and according resource scarcity is to take a square-root? Ha ha hah ha ha ha ha ha ha ha!

Keynes warned: "The fact that two incommensurable collections of miscellaneous objects cannot in themselves provide the material for a quantitative analysis need not, of course, prevent us from making approximate statistical comparisons, depending on some broad element of judgment rather than of strict calculation, which may possess significance and validity within certain limits. But the proper place for such things as net real output and the general level of prices lies within the field of historical and statistical description, and their purpose should be to satisfy historical or social curiosity, a purpose for which perfect precision—such as our causal analysis requires, whether or not our knowledge of the actual values of the relevant quantities is complete or exact—is neither usual nor necessary. To say that net output to-day is greater, but the price-level lower, than ten years ago or one year ago, is a proposition of a similar character to the statement that Queen Victoria was a better queen but not a happier woman than Queen Elizabeth—a proposition not without meaning and not without interest, but unsuitable as material for the differential calculus. Our precision will be a mock precision if we try to use such partly vague and non-quantitative concepts as the basis of a quantitative analysis..."

Keynes was right. I know he was right. I do it anyway.

Hold these figures in your head as a very rough guide to the amount by which humanity was richer in 2010 than it was in 1870—and never forget that the riches were vastly more unequally distributed around the globe in 2010 than they were in 1870.

That last is a puzzle: communications and transportation around the entire globe was SO much easier in 2010 than it has been in 1870. So why then was the world a more unequal place, looking across countries, in 2010 than it had been in 1870? Nay, not just a more unequal place, but a grossly and extraordinarily more unequal place.

A 2.1 percent per year growth rate is a doubling every 33 years.

Trying to remind the non-quantitative just what consistent 2.1%/year growth is: doubling in 33 years, multiplying eight-fold in a century, multiplying 64-fold in two centuries. That is the pace of underlying technology growth the world experienced over 1870-2010.

That [the 2.1 percent per year average annual technology growth rate starting in 1870] meant that the technological and productivity economic underpinnings of human society in 1903 were profoundly different from those of 1870—underpinnings of industry and globalization as opposed to ones that were still agrarian and landlord-dominated. The mass-production underpinnings of 1936, at least in the industrial core of the global north, were profoundly different also. But the change to the mass consumption-suburbanization underpinnings of 1969 was as profound, and that was followed by the shift to the information-age microelectronic-based underpinnings of 2002. A revolutionized economy every generation cannot but revolutionize society and politics, and a government trying to cope with such repeated revolutions cannot help but be greatly stressed in its attempts to manage and provide for its people in the storms.

Let me stress this: humanity had never before seen anything like this pace of economic transformation. Not just production, but newly-transformed production and the further transformation of production became the principal work-life business of humanity. As much economic change and creative destruction as had taken place over 1720-1870 took place every 33 years after 1870. And the pace of change over 1720-1870 had already been more than fast enough to shake societies and polities to pieces. "All that is solid melts into air", Marx and Engels had written in 1848: all established hierarchies and orders are steamed away. And they had no real idea what was coming: the pace of worldwide change of their day was less than 1/4 of what it would become after 1870.

Much good, but much ill also flowed [from the creative-destruction well-nigh complete revolutionizing of the economy every generation post-1870]: people can and do use technologies—both the harder ones, for manipulating nature, and the softer ones, for organizing humans—to exploit, to dominate, and to tyrannize. And the long twentieth century saw the worst and most bloodthirsty tyrannies that we know of.

More of a proportional increase in humanity's deployed technological prowess every 23 years after 1870 than was seen in the entire 1770-1870 Industrial Revolution century. (And more than in the entire 1500-1770 Imperial-Commercial Revolution Age. And more than over all of 800-1500.) These repeated generation-after-generation technological shifts upended and revolutionized economies. The associated repeated creative destruction upended societies as well. This posed two problems for governments: How were they to deal with the "destructive" part of creative destruction as it upended the lives of their people? And how were they to deal with neighboring governments that decided to use enhanced technological powers for evil for destruction and oppression? At the sharp end, a government gone horribly wrong was a genocide-scale problem for the people under its boot, and for the people who were that government's neighbors. The 20th century saw the worst tyrannies ever.

All that was solid melted into air—or rather, all established orders and patterns were steamed away. Only a small proportion of economic life could be carried out, and was carried out, in 2010 the same way it had been in 1870. And even the portion that was the same was different; even if you were doing the same tasks that your predecessors had done back in 1870, and doing them in the same places, others would pay much less of the worth of their labor-time for what you did or made. As nearly everything economic was transformed and transformed again—as the economy was revolutionized in every generation, at least in those places on the earth that were lucky enough to be the growth poles—those changes shaped and transformed nearly everything sociological, political, and cultural.

The wave of technological progress at an unprecedented pace—one that puts even the 1770-1870 Industrial Revolution Century to shame, and that packs as much into one year as we saw in 50 pre-1500 years—and the associated creative-destruction wealth-generating process of repeated revolutionizing and transformation of the economy is THE central underlying process of 20th-century history.

All else has to adapt, or fail to adapt, to that. And all else did—or failed to do so. That is why the history of the 20th century took the form that it did.

PREORDER! <https://bit.ly/3pP3Krk>

Suppose we could go back in time to 1870, and tell people then how rich, relative to them, humanity would become by 2010. How would they have reacted?

Remember: as much proportional increase in technological prowess over 1870 to 2010 as was seen over -4000 to 1870. And essentially all the potential benefits over the earlier period were eaten up by population growth and the relative resource scarcity that it generated. Nearly 6000 years of historical progress crammed into a century. What would our predecessors back in 1870 have rationally thought would be the result?

They would almost surely have thought thatthe world of today would be a paradise, a utopia. People would have 8.8 times the wealth? Surely that would mean enough power to manipulate nature and organize humans that all but the most trivial of problems and obstacles hobbling humanity could be resolved.

People in 1870, after all, thought that humanity had outgrown fighting over God. They fought—in one way or another and for one reason or another—over resources. They would have thought that in the world of 2010, with 20x the technological resources of 1870, jostling and fighting to get even more resources would have a much lower priority relative to turning your skill and energy to doing what you ultimately wanted to do with those resources. Consider Lenin's "State and Revolution": In a capitalist.future society of material abundance, scarcity must be artificially and brutally created:

The state in the proper sense of the word, that is, a special machine for the suppression of one class by another, and, what is more, of the majority by the minority. Naturally, to be successful, such an undertaking as the systematic suppression of the exploited majority by the exploiting minority calls for the utmost ferocity and savagery in the matter of suppressing, it calls for seas of blood, through which mankind is actually wading its way in slavery, serfdom and wage labor....

During the transition from capitalism to communism suppression is still necessary, but it is now the suppression of the exploiting minority by the exploited majority.... It is no longer a state in the proper sense of the word; for the suppression of the minority of exploiters by the majority of the wage slaves of yesterday is comparatively so easy, simple and natural a task that it will entail far less bloodshed than the suppression of the risings of slaves, serfs or wage-laborers....

And it is compatible with the extension of democracy to such an overwhelming majority of the population that the need for a special machine of suppression will begin to disappear.... The exploiters are unable to suppress the people without a highly complex machine... but the people can suppress the exploiters even with a very simple “machine”....

Communism makes the state absolutely unnecessary, for there is nobody to be suppressed—“nobody” in the sense of a class.... We are not utopians, and do not in the least deny the possibility and inevitability of excesses on the part of individual persons, or the need to stop such excesses.... [But] this will be done... as simply and as readily as any crowd of civilized people... interferes to put a stop to a scuffle or to prevent a woman from being assaulted.... We know that the fundamental social cause of excesses... [of] violation[s] of the rules of social intercourse, is the exploitation of the people, their want and their poverty. With the removal of this chief cause, excesses will inevitably begin to "wither away". We do not know how quickly and in what succession, but we do know they will wither away. With their withering away the state will also wither away.

Compare to Robert A. Heinlein's libertarian utopia of "The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress", in which the ungoverned convicts" of the Lunar ice-mining settlement deal with crimes by grabbing somebody to serve as a judge, having him hear the case, and then putting the guilty party out of the airlock into the vacuum.

The answer to the questions: Where moon? Where Lambo? Where Utopia? was:

Not here. By 2010 it had been 150 years [of doubling technological prowess every generation]. We did not run to the trail’s end and reach utopia. We are [at best] still on the trail—maybe, for we can no longer see clearly to the end of the trail, or even the direction the trail we are on is leading us in.

Let me ask you to note how remarkable this disappointment is. All previous this-world utopias—starting from Thomasso Campanella's 1602 La città del Sole <https://archive.org/details/thecityofthesun02816gut…> or Francis Bacon's New Atlantis <https://archive.org/details/fnewatlantis00baco…> on up through Lenin's State and Revolution >https://marxists.org/ebooks/lenin/state-and-revolution.pdf…> had managed to construct, in their imagination, more-than-satisfactory utopias with only a small amount of the technological power to manipulate nature and to organize humans in our highly, highly-productive 8 billion-strong division of labor that we have today. Considered as an anthology intelligence, humanity is inept, and not sane.

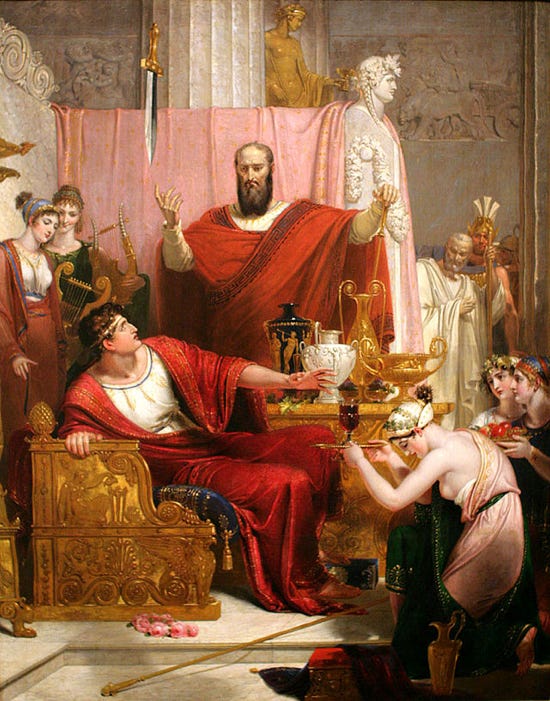

This is, perhaps, the place to tell the story Plutarch tells, of King Pyrrhus and his advisor Cineas: Plutarch:

[Cineas:] 'When all [kingdoms] are in our power what shall we do then?' Said Pyrrhus, smiling, 'We will live at our ease, my dear friend, and drink all day, and divert ourselves with pleasant conversation.' When Cineas had led Pyrrhus with his argument to this point: 'And what hinders us now, sir, if we have a mind to be merry, and entertain one another, since we have at hand without trouble all those necessary things, to which through much blood and great labour, and infinite hazards and mischief done to ourselves and to others, we design at last to arrive?' Such reasonings rather troubled Pyrrhus with the thought of the happiness he was quitting, than any way altered his purpose, being unable to abandon the hopes of what he so much desired.

For an entire anthology-intelligence species to properly set and balance ends and means in order to successfully accomplish what its best self truly desires is, of course, much harder considered as a coordination problem than for an individual brain controlling a single animal organism to do so. Nevertheless, the second key to the history of the 20th century, just behind the key that is the understanding of the enormous unprecedented leap forward in our technological prowess, is the recognition of how unintelligently humanity has chosen and is choosing the goals it is devoting its anthology-intelligence focus to pursuing.

What went wrong? Well, Hayek may have been a genius, but only the Dr. Jekyll-side of him was a genius. He [Hayek] and his followers were extraordinary idiots as well.

Truth be told, I actually think Hayek was about 1/4 genius and 3/4 idiot. Is macroeconomics was completely stupid, and enormously at variance with his microeconomic insights as well. That the extremely clever market economy could not find a way to respond to a monetary injection (whether coming from a gold discovery or a central bank expansion) other than by grossly over-investing in excessively roundabout and long-term unsustainable production processes? That having so over-invested, it had no way to unwedge itself than to shift huge numbers of workers from now low-productivity investment-goods production to zero-productivity unemployment? Come on! Be serious! His respect for the time-honored wisdom of the of the ages in human social organization combined with his contempt for such and for all countervailing-power institutions in the economy? Ludicrous. ‘And then there is the dodging-and-weaving Hayek: complaining to Paul Samuelson about the "malicious distortion" Samuelson committed by summarizing Hayek's position as "government modification of market laissez-faire must lead inevitably to political serfdom", yet in his 1956 forward to The Road to Serfdom we find:

Six years of [Labour Party] government in England have not produced anything resembling a totalitarian state. But those who argue that this has disproved the thesis of The Road to Serfdom have really missed... that the most important change which extensive government control produces is a psychological change... over... generations.... The change undergone by the character of the British people... can hardly be mistaken... The British experience convinces me... is that the unforeseen but inevitable consequences of socialist planning create a state of affairs in which... totalitarian forces will get the upper hand.

Macro, society-economy, rhetorical honesty—against those three faces of the Bad Hayek we have the Good information-theoretic Hayek, who is very good indeed: https://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2014/08/over-at-equitable-growth-yet-another-note-on-mont-pelerin-thinking-some-more-about-bob-solows-view.html… You can quibble that Michael Polanyi saw further and deeper, and that Polanyi's distinction between "mercenary" and "fiduciary" modes of human activity is of decisive importance for understanding the proper place of the market in society, and you would be right. But Hayek got to the mountaintop to see what was on the other side first. <https://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2014/08/over-at-equitable-growth-yet-another-note-on-mont-pelerin-thinking-some-more-about-bob-solows-view.html>

They [Mr. Hyde-Hayek and his idiot followers] also thought the market alone could do the job—or at least all the job that could be done—and commanded humanity to believe in the workings of a system with a logic of its own that mere humans could never fully understand: “The market giveth, the market taketh away; blessed be the name of the market.” They thought that what salvation was possible for humanity would come not through St. Paul of Tarsus’s solo fide but through Hayek’s solo mercato. But humanity objected.

Karl Polanyi wrote that the Hayekian project, in which humanity is made rich as a byproduct of profit-motivated economic agents responding to the price signals sent by the rich was a:

stark utopia. Such an institution could not exist for any length of time without annihilating the human and natural substance of society; it would have physically destroyed man and transformed his surroundings into a wilderness. Inevitably, society took measures to protect itself, but whatever measures it took impaired the self-regulation of the market, disorganized industrial life, and thus endangered society in yet another way. It was this dilemma which forced the development of the market system into a definite groove and finally disrupted the social organization based upon it

Think of it: Your community and its associated land-use and sociability patterns ("land"), your occupations and its remuneration on a scale appropriate to your status and to your desert resulting from your applying yourself ("labor"), and the very stability of and your ability to be paid for performing your job at all (“finance”)—all of these melt into air if they do not satisfy some maximum-profitability-use-of-resources test (“fictitious commodities”) imposed by some rootless cosmopolite thousands of miles away. Furthermore, it is a maximum-profitability test that is applied, not a societal-wellbeing test The (competitive, externality-free, in-equilbrium) market system definitely and certainly maximizes something. But what it maximizes is not any idea of the well-being of society, but rather the wealth-weighted satisfaction of the rich.

So society responded: people believe that they have other rights rather than property rights (which are valuable only if your particular piece of property is useful for producing things for which the rich have a serious jones). And so they strove to organize society to vindicate those other Polanyian rights. And so society did so by attacking the market, and by attacking all of those it saw as its internal and external enemies that the global market system was empowering to oppress them.

Polanyi, writing in 1943 and thereabouts as Rotmistrov threw his 5th Guards Tank Army T-34s into the abattoir at Prokhorovka in an insanely one-sided loss ratio to keep the Nazi SS tank divisions "Adolf Hitler's Bodyguards", "The Empire", and "Death's Head" from breaking through in the one operation that might have won the Battle of Kursk for the Nazis, the most striking thing about this double movement—the market attempts to destroy society in the interest of creative-destruction and satisfying the desires of the rich, society strikes back—was the extraordinary size and violence of the cataclysm that, from 1914 to 1945, destroyed human progress that had, during the 1870 to 1914 Belle Époque, seemed a marvelous and unmerited miraculous and stable gift to humanity. "Economic El Dorado", in Keynes's words in 1919. Polanyi:

No explanation can satisfy which does not account for the suddenness of the cataclysm. As if the forces of change had been pent up for a century, a torrent of events is pouring down on mankind. A social transformation of planetary range is being topped by wars of an unprecedented type in which a score of states crashed, and the contours of new empires are emerging out of a sea of blood. But this fact of demoniac violence is merely superimposed on a swift, silent current of change which swallows up the past often without so much as a ripple on the surface! A reasoned analysis of the catastrophe must account both for the tempestuous action and the quiet dissolution.

Polanyi wrote at the midpoint of the 1870-2010 Long 20th Century. After 1945 things were put back together, and there was another age, a Super-Belle Époch, the Thirty Glorious Years of social democracy, during which the great and good of humanity, at least in the North Atlantic plus Japan, could think that they had finally gotten it right. It was attained not by returning to a more purified and ruthless version of the pseudo-classical semi-liberal Hayekian system, not by building the New Man in the New Order of market-free Socialism, and not by recognizing that good societies are unified communities for which their charismatic leaders serve as the thongs that bind the bundle of sticks together, and so make the Fascist people strong.

It was attained, rather, by compromises cobbled-together. John Maynard Keynes with a shotgun blessing the hasty wedding-under-duress of Friedrich A. von Hayek and Karl Polanyi. But that social-democratic order did not pass its own sustainability test, and gave way to neoliberalism, which repeatedly failed to deliver the goods, and now here we are.

The market economy solved the problems that it set itself [of making humanity rich as a byproduct of fulfilling the desires of those with valuable property rights—getting the rich their luxuries and the middle-class their conveniences]—but then society did not want those solutions. It wanted solutions to other problems, problems that the market economy did not set itself, and for which the crowdsourced solutions it offered were inadequate. It was, perhaps, Hungarian-Jewish-Torontonian moral philosopher Karl Polanyi who best described the issue. The market economy recognizes property rights. It sets itself the problem of giving those who own property—or, rather, the pieces of property that it decides are valuable—what they think they want. If you have no property, you have no rights. And if the property you have isnot valuable, the rights you have are very thin indeed.

Cf.:

As I wrote back then: I remember back in the… spring of 1981, I think it was. I asked my professor, William Thomson, visiting from Rochester, roughly this: "The utilitarian social welfare function is Ωu = U(1) + U(2) + U(3)… The competitive market economy maximizes a market social welfare function Ωm = ω(1)U(1) + ω(2)U(2) + ω(3)U(3)…, where the ω(i)s are Negishi weights that are increasing functions of your lifetime wealth W(i)—indeed, if lifetime utility is log wealth, then ω(i)=W(i). Market failures drive wedges between what the economy achieves and what it could achieve. There are massive, massive differences between the Ωu that is the true social welfare function and the function Ωm that the well-working market maximizes. Why isn’t the unequal distribution of ex ante expected lifetime income—inequality of opportunity—conceptualized by US economists as the greatest of all market failures?" Thomson did not have a good answer.

My other teacher Joe Kalt, however did—an answer that old Freddie from Barmen and Charlie from Trier would have endorsed. People who talk about the Pareto-optimality of the market rather than about the divergence between the market's and the real Societal-Wellbeing Function are in the business of justifying that wealth—however acquired—should be the source of social power, and they are not in the business of working for the public interest. Most are in this business because it is relatively lucrative.

Others have a somewhat deeper rationale. Friedrich von Hayek, for example, was convinced to his dying day and beyond that no better political-economic system than the market and private property could be devised, and that attempts to do so inevitably put us on the road to, well, serfdom. Thus justifications of the "optimality" of the market perform the same function in Hayek's Republic as the claim that those chosen to be guardians have souls of gold perform's in Plato's. But Plato never claims that the purveyors of the noble lie that beguiles the citizens of his Republic were philosophers.

But people think they have other rights [than property rights, which are themselves only worth anything only if their property is valuable]—they think that those who do not own valuable property should have the social power to be listened to, and that societies should take their needs and desires into account. Now the market economy might i n fact satisfy their [the non-rich's] needs and desires. But if it did so, it did so only by accident: only if satisfying them happens to conform to a maximum-profitability test performed by a market economy that is solving the problem of getting the owners of valuable pieces of property as much of what the rich want as possible.

The idea that the market economy is a societal machine for satisfying the desires not of the people, but rather of the people with disposable income—that is an old one, dating back to the mid-1700s and to Richard Cantillon's "Essay on the General Nature of Commerce". But it is not one that is highlighted in most economics courses—that the market listens to you more-or-less in proportion to your disposable wealth. That is instead hidden beneath the statement that the market considers your wishes according to your willingness-to-pay—as if it were purely a matter of individual will, rather than at least as much a matter of the social power your wealth assigns to you.

When I teach Econ 1, I replace "willingness to pay" with "intensity of desire times wealth." In general, in a market economy, if you have property or skills both useful for producing things for which the rich have a serious Jones and scarce, he will do OK. Otherwise not so much. Moreover, even if you are doing okay now, the creative destruction of the market system, especially in the long 20th century in which human technological capabilities are doubling and thus the economy is being revolutionized every generation creates great instability: if the particular value chain in which you are enmeshed shifts, or if your particular bargaining power within it changes up, whatever economic position and social power you have may will vanish overnight as the fabric of your life fails to pass some maximum-profitability test inflicted by some rootless cosmopolite financier thousands of miles away.

THIS IS NOT HOW PEOPLE THINK THEIR SOCIETY SHOULD WORK!!

As Karl Polanyi put it, the market system attempts to create a "stark utopia" by destroying all sources of social power and all societal bonds except those mediated by wealth. And society—which has very different ideas about who should have social power and who should be listened to—reacts, by trying to damage the market system and damage those whom it decides are the rootless cosmopolites and their allies who are misusing it to the detriment of the people, the real, essential, worthy people. This has a long history. When Karl Marx began writing, the word he used for the concept he later labelled "bourgeois" was "Jewishness".

So throughout the long twentieth century, communities and people looked at what the market economy was delivering to them and said: 'Did we order that?'”.

That last reference is to Nobel Prize-winning physicist I.I. Rabi's quip in response to the identification of the muon—an elementary particle that seemed then to be nothing other than a much heavier version of the electron. The point is that the industrializing market economy in the context of much more rapid technological progress fueled by the phase-shift from the coming of full globalization, the industrial research lab, and the modern was certainly producing something. But it was not producing what humanity had ordered for the era of progress that visionaries had hoped would be launched by the Belle Époque that began in 1870. It was not producing anything that could be called a real utopia, substantially because the market economy was solving the problem of getting those who owned valuable property the luxuries they thought they wished, rather than solving the problem of making a truly human world for us all.

And society demanded something else, The idiot Mr. Hyde-side of Friedrich von Hayek called it [what society demanded in addition to the vindication of property rights] 'social justice', and decreed that people should fuggedaboudit: the market economy could never deliver social justice, and to try to rejigger society so that social justice could be delivered would destroy the market economy’s ability to deliver what it could deliver—increasing wealth, distributed to those who owned valuable property rights.

In a way, von Hayek's point-of-view was as mystical as Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky's. Edmund S. Wilson noted, in his "To the Finland Station", that what Trotsky at least wrote made absolutely no sense unless you replaced "history" and "dialectic of history" with "Providence" and "God". Hayek has a very similar attitude toward the catallaxy. It was not designed by humanity. It cannot be improved by humans. For humans to even question it is impious, a violation of taboo, and brings down awful retribution and judgment.

Much wiser than von Hayek, I think, was Michael Polanyi, for whom both fiduciary and mercenary institutions have their proper place, and they can be (partially) designed, improved, and kept within their proper bounds by humans acting consciously and collectively.

Do note that in this context [the] 'social justice' [thata society demanded] was always only 'justice' relative to what particular [powerful] groups desired: not anything justified by any consensus transcendental principles. Do note that it was rarely egalitarian: it is unjust if those unequal to you are treated equally. But the only conception of 'justice' that the market economy could deliver was what the rich might think was just, for the property owners were the only people it cared for."

If we were to give Friedrich von Hayek the mic, he would say that the attempts by holders of other forms of social power to upend the workings of the market had to be destructive in terms of their effect on wealth-creation, and were at best neutral in terms of their effects on wealth-distribution. They brought more chaos and uncertainty to an already chaotic world, and so risk aversion made them a bad idea even if their revolutions could be quick and relatively painless. The social fabric of the Habsburg Empire was nothing to be proud of, but there was no gain in expected value by replacing it with one imposed by storm troopers, whether Steel Helmets or Red Guards or the ethno-nationalism of some particular relatively small grouping of valleys. The moral arc of the universe, von Hayek would have said, does not bend toward justice. Only a fool thinks it does. So all we can do is to try to calm everybody down, keep the (social) peace, and let obedience to market forces deliver what they can deliver—and they can deliver marvelous things. From the standpoint of the 20th-century history of Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Zagreb, Belgrad, or Cracow, Hayek's argument looks rather strong. It looks less strong from the standpoint of London, Paris, New York, or Los Angeles.

Plus, the market economy is powerful but very very imperfect even on its own terms of reference. It cannot by itself deliver enough research and development, for example, or environmental quality, or, indeed, full and stable employment.

The problems of "externalities "and "market power ": anytime there is somebody who is not a participant in a bargain who is materially affected by its terms and conditions, the argument that a bargain is win-win with no downside fails. And anytime there is not somebody just down the street able to offer an alternative bargain just as good, holdup problems will ensure that the market leaves substantial wealth on the table. A well-functioning market economy needs very aggressive antitrust and price-posting to support it. A well-functioning market economy needs an enormous structure of Pigovian taxes and subsidies to point it in the right direction.

There is, in Chicago-School folklore, a very strange belief that Ronald Coase with his "The Problem of Social Cost", disproved Pigou: that there are no externalities, there are only transaction costs resulting mostly from the failure to properly set up initial property rights by appropriately carving up the beast "at the joints" so that the relevant parties could make the needed externality-incorporating arrangements. There are references to a 1959 dinner at the house of Aaron Director,.where Coase convinced 20 initially very skeptical economists, including Friedman and Stigler, that Pigou was simply "wrong".

What was supposed to be Coase's argument-clinching point—that if the farmer has the right to keep sparks from the locomotive from.lighting his crops on fire, the railroad gets to decide whether to buy out that right or not; while if the railroad has the right to emit sparks, the farmer gets to decide whether to buy out that right or not, and so there is not an "externality" but merely a "transaction cost" (i.e., in this case a "holdup") problem. Thus it does not matter who holds the property right as long as somebody holds it. Now that argument is simply wrong. If the railroad has the property right, it installs a flamethrower on top of.the locomotive before the bargaining begins. It doesn't do that if the farmer has the property right.

Moreov3r, a world in which there are no significant transaction costs... that is not a market economy, that is a free society of associated producers—a verydifferent thing indeed. The claims that "the market will take care of it", and that government failure is always and everywhere a bigger danger than market failure rest on the claim that market failures are typically small. Yet that claim is ideological in the extreme, not empirical at all.

No:’ ‘The market giveth, the market taketh away; blessed be the name of the market' was not a stable principle around which to organize society and political economy. The only stable principle had to be some version of 'The market was made for man, not man for the market'.

The references, of course, are to Job 1:21: "And [he] said 'Naked came I out of my mother's womb, and naked shall I return thither: the Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.'" And Mark 227: "And he said unto them, 'The sabbath was made for man, and not man for the sabbath'. The.point is that human societies will not long stand for the inversion of values associated with the apotheosis of the Mammon of Unrighteousness. Society must work or must at least be perceived to work on a human scale. Now there is an argument that simply letting the market rip and hoping for the best is the best attainable option. But that can be sustained only when the "creation" part of Schumpeter's creative destruction is very large, and the "destruction" part unusually small. How to accomplish that is to borrow a phrase my teacher Charlie Kindleberger used in a different context, "a neat trick... sleight of hand, some trick with mirrors". The problem is that those who worship the Mammon of Unrighteousness that is the market cannot understand that hard and clever work is required to make that happen. They do not understand that in order to make that happen you actually need mechanics so that the two boats can sail, and the one helicopter can fly, in the terms of the old joke.

But who were the men who counted, for whom the market should be made? And what version would be the best making? And how to resolve the inevitable squabbles over the answers to those questions?

Simply concluding that the creative-destruction of the technological progress-fueled market had to be somehow leashed got humanity to precisely nowheresville. Humanity needed a plan. And it needed to be a good plan. Much of the failure of humanity to use its technological powers during the Long 20th Century 1870-2010 to approach utopia had to do with the absence of a good plan, or indeed of any .coherent plan at all, or even of a mechanism to filter possible plans to reach near-consensus on one probably-good one that then could be turned into running code.

John Maynard Keynes saw this lack in the early 1920s, and expressed it well in a review he wrote of the work of Leon Trotsky <https://marxists.org/history/etol/document/comments/keynes01.htm…>: Keynes:

Granted his assumptions, much of Trotsky’s argument is... unanswerable.... But what are his assumptions? He assumes that the moral and intellectual problems of the transformation of Society have been already solved—that a plan exists.... He is so much occupied with means that he forgets to tell us what it is all for. If we pressed him, I suppose he would mention Marx. And there we will leave him with an echo of his own words—'together with theological literature, perhaps the most useless, and in any case the most boring form of verbal creation.' Trotsky’s book must confirm us in our conviction of the uselessness, the empty-headedness of Force at.the present stage of human affairs.... We lack more than usual a coherent scheme of progress, a tangible ideal. All the political parties alike have their origins in past ideas and not in new ideas – and none more conspicuously so than the Marxists. It is not necessary to debate the subtleties of what justifies a man in promoting his gospel by force; for no one has a gospel. The next move is with the head, and fists must wait.

In the Thirty Glorious Years after World War II, it seemed as though mixed-economy social-democracy was the plan, but that failed its political sustainability test in the 1970s. At the end of the 1990s many (including me) claimed that "soft" left-neoliberalism was the plan, but its failure to surpass the bar has been far more glaring than social democracy's failures in its day. And "hard" right-neoliberalism has delivered on none of its promises save to create and entrench a corrupt plutocracy.

So we are still waiting.

As Max Weber <https://soc.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/Weber-Science-as-a-Vocation.pdf> once wrote:

For the many who tarry today for new prophets... the situation is the same as... the... song of... exile...

Watchman, how much longer will this dark night last?' 'The morning will come, but then the night will return. Ask when you want to. And return to ask again.

From this we want to draw the lesson that nothing is gained by yearning and tarrying by themselves, and we shall act differently. We shall set to work and meet 'the demands of the day' in human relations as well as in our vocations...

But in spite of what Weber tries to claim at the end of "Wissenschaft als Beruf", meeting 'the demands of the day' without a prophet with a good plan is not easy. Not easy for each of us. Not easy for all of us.

Throughout the long twentieth century, many others—Karl Polanyi, John Maynard Keynes, Benito Mussolini, and Vladimir Lenin serve as good markers for many of the currents of thought, activism, and action—tried to think up solutions.

How do you keep—or perhaps improve upon—the incentives for efficient production, rapid creative destruction, and technological advance that the private-property market economy provides, without also buying into its proviso that only property conveys rights that allow one to count in the eyes of society's decision-making processes? Keynes thought the problem could be.finessed with an extremely light-handed amount of central planning: full-employment policy, and the euthanization of the rentier class by the low interest rates need to implement full-employment policy, would do enough of the job to make the economic problem cease being a bigger deal than the problem of the continued survival of Disco.

Karl Polanyi thought that human recognition of society's demands for more rights than property rights would be the key:

Acceptance of the reality of society gives man indomitable courage and strength.... As long as he is true to the task of creating more abundant freedom for all, he need not fear that either power or planning will turn against him and destroy the freedom he is building by their instrumentality.

That peroration may have satisfied Polanyi, but I have no idea what it means.

Mussolini took the strength of ethno-nationalism to teach the lesson, as Polanyi says, that humans must "resign [themselves] to relinquishing freedom and glorif[y the] power which is the reality of society", just as a single stick that claims to be free is soon broken, while if it loses its freedom in a stick-bundle tied with leather thongs it becomes a mighty force in the hand of its wielder.

Lenin suffered from the infantile mental disorder of believing that upon the removal of the market the oppressive state would also wither away, and all would be very simple and easy, for:

Accounting and control necessary... have been simplified by capitalists to the utmost and reduced to the extraordinarily simple operations—which any literate person can perform—of supervising and recording, knowledge of the four rules of arithmetic, and issuing appropriate receipts.

Thus:

They [Polanyi, Keynes, Mussolini, Lenin, and uncountably many others] dissented from the pseudo-classical (for the order of society, economy, and polity as it stood in the years after 1870 was in fact quite new), semi-liberal (for it rested upon ascribed and inherited authority as much as on freedom) order that Hayek and his ilk advocated and worked to create and maintain. They did so constructively and destructively, demanding that the market do less, or do something different, and that other institutions do more.

As I said above, recognition that people reject the idea that social power .should be distributed according to wealth (whether earned, windfall, or inherited) and mediated purely through the cash nexus is not an answer to the problem of managing creative destruction, but merely a recognition that there is a question. The answer remains opaque and obscure. Finding an answer became an extremely pressing need after 1870, as technological progress doubled humanity's collective powers to manipulate nature and organize themselves not every 1450 years (as in the pre-1500 Agrarian Age), not every 500 years (as in the 1500-1770 Imperial-Commercial Age), not every 160) years (as in the 1770-1870 Industrial Revolution Age, but every 35 years in the post-1870 Modern Economic Growth Age. Without an answer, and a good answer, to how to manage such a pace of creative destruction, society would react against the logic the market was imposing on it, and in the process smash things to bits.

Perhaps the closest humanity got [to the road to a real utopia, to a truly human world] was the shotgun marriage of Hayek and Polanyi, blessed by Keynes, that took form in post-World War II North Atlantic developmental-state social democracy. But that institutional setup failed its own sustainability test. And so we are still on the path, not at the end, and unsure whether the path leads anywhere.

And so we are still, at best, slouching toward utopia.

That the pseudo-classical semi-liberal order of the 1870-1914 Belle Époque fell apart into so many different catastrophes after 1914 is readily comprehensible. Governments and élites failed to manage economic creative-destruction at the fever-heat pace at which it lurched forward after 1870, as full globalization, the industrial research lab, and the modern corporation all came on stream. The failure-to-manage led to many, many societal reactions against the ongoing rush of claims that all was OK—that "the market giveth, the market taketh away: blessed be the name of the market". The demands and then the attempts to build a better New Order—or rather, multiple attempts to do so—turned at least Europe into a hellhole and an abattoir until 1945.

And then things were somehow righted. And history began to rhyme, as the pattern of an upward lurch to unprecedented economic growth and technological change after 1870 that created the Belle Époque was followed by another upward lurch to super-unprecedented economic growth after 1945 that created the Thirty Glorious Years of social democracy: the most golden of Golden Ages, as far as visible progress toward a true utopia, a truly human world, was concerned.

Yet it did not last: by the late 1970s social democracy failed its political-economy sustainability test, in a way somewhat reminiscent of post-1914 loss of confidence in pseudo-classical semi-liberalism. Yet why the judgment of the Great and Good—and of the voters at the polls—that what was needed was A Neoliberal Turn remains obscure to me, even though I lived through it.

With sentence 86, my "Slouching" reaches the first of its pauses. By this point I have run through my Grand Narrative, which I chose not because it was true but because it was the least false one I could think of, and I badly needed a Grand Narrative on which to hang the structure of the book.

The one I chose is, broadly, a Polanyian one. And I freely avow myself a pupil of that mighty thinker. But instead of turning him on his head, I have merely mixed him with flavors of Keynes and von Hayek. (Alas! I have not managed to also mix in the flavors of Schumpeter, Popper, Drucker, and Karl Polanyi's younger brother Michael. That would have required a book with pages numbering in the four digits, which Basic would have been very unlikely to publish. But I dearly feel the absence.)

Now, in the next passage in my manuscript, I turn to defending and explaining why I feel I have to have a Grand Narrative at all, and why the one I have chosen has the virtue of being least-false:

Return to my claim above that the long twentieth century was the first century in which the most important historical thread was the economic one. That is a claim worth pausing over.

The [long 20th] century saw, among much else, two world wars, the Holocaust, the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, the zenith of American influence, and the rise of communist China. How dare I say that these are all aspects of one primarily economic story? Indeed, how dare I say that there is one single most consequential thread?"

Let alone boldly and baldly assert that that single most consequential thread was the economic one?

Technological advance in the context of a globalized market economy as the coming of modern science assisted by the industrial research lab and the modern corporation discovered, developed, deployed, and then diffused enough new technologies—enough new and better ideas about how to manipulate nature and organize humans—to double humanity's collective technological prowess every generation, and thus to revolutionize and re-revolutionize the economy every single generation from 1870 to 2010. How dare I assert that, you ask?

I dare assert it because it is true.

And you cannot understand even a smidgeon of history over 1870 to 2010 without starting from d deep grasp of that economic process and its impact on everything else.

I dare [assert my Grand Narrative that the economic thread is by far the most important thread of the history of the long 20th century] because we have to tell grand narratives if we are to think at all. Grand narratives are, in the words of that bellwether twentieth-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, 'nonsense.' But, in a sense, all human .thought is nonsense: fuzzy, prone to confusions, and capable of leading us astray. And our fuzzy thoughts are the only ways we can think—the only ways we have to progress. If we are lucky, Wittgenstein said, we can 'recognize…. them as nonsensical', and use them as steps 'to climb beyond them . . . [and then] throw away the ladder'—for, perhaps, we will have learned to transcend 'these propositions' and gained the ability to 'see the world aright'.

This is a personal milestone: I have never had occasion to quote Ludwig Wittgenstein before.

I am trying at this point in the manuscript to pull off a double movement: First, to assert the "truth" of my Grand Narrative—for it is true, or rather if you do not presume that it is true you cannot think about the history of the long 20th century at all. Second, that the Grand Narrative is false—a crutch that we need because our East African Plains Ape monkey-brains can only think in narratives. Thus it is a crutch that is essential to us. But it is a crutch that breaks when .we lean on it.

I really do not know how to think about this: Paradox of knowledge? Paradox of ignorance? The ultimate "motte & bailey" intellectual move?

It is in hopes of transcending the nonsense to glimpse the world aright that I’ve written this grand narrative. It is in that spirit that I declare unhesitatingly that the most consequent thread through all this history was economic.

In short, if you are to understand anything at all about the history of the long 20th century—if your thoughts are to be even somewhat coherent, and somewhere in the neighborhood of what a much vaster scrutinizing intelligence might call "the truth", you have to start from the premise that the axis around which history revolved from 1870-2010 was that of the economic trends, events, patterns, and transformations that rocked the world, not once, but every single generation again and again and again.

Moreover, you have to hold tight to the true knowledge that the long 20th century was the first century in which this was true. In all previous centuries—with the partial exception of 1770-1870—the economic side was the painted backdrop in front of which the play proceeded, with the economy becoming a protagonist in history only when we stepped back from any single-century perspective and took the millennial perspective of the longue durée.

The British Industrial Revolution century was a partial—a very partial—exception to this. In the radius-300 miles "Dover Circle" and its offshoot economies, by 1870 humanity's discovered, developed, deployed, and diffused technological prowess stood at 2.5x its level of 1770.

By 1870, in the "Dover Circle" plus offshoots, roughly and approximately, on average what it had taken 250 workers to do in 1770 it took only 100 workers to do in 1870. That economic change had upended society, culture, and politics within the "Dover Circle" (plus offshoots). But it had only done so once. And it had taken 100 years. '

After 1870, that much economic creative-destruction upending everything else would take place every generation.

And if we step outside the 300-mile radius Dover Circle, and look at the world as a whole? For the world as a whole humanity's deployed technological prowess was only some 3/5 higher than it had been in 1770.

That was certainly enough to shake thrones and altars and shift patterns of authority, hierarchy, coordination, and gift- and market-exchange. But outside the Dover Circle, the meat and fish of history over 1770-1870 remained the dance of culture, society, war, conquest, and politics, with the economic being the scene backdrop and arranging the furniture on stage before and as the actors entered and the play of history began.

Before 1870, over and over again, technology lost its race with human fecundity, with the speed at which we reproduce.

Simply reminding readers that humanity was ensorcelled by the Devil of Malthus before the start of the Long 20th Century: improvements in technology flow overwhelmingly to increasing human numbers, very secondarily to the material benefit of the rich, (and tertiarily to sharpening the incentives of the powerful to dominate and their capabilities to do so,) and otherwise leave humanity stuck in poverty without positive liberty, living "the same life of degradation and imprisonment" in the words of John Stuart Mill.

Greater numbers, coupled with resource scarcity and a slow pace of technological innovation, produced a situation in which most people, most of the time, could not be confident that in a year they and their family members would have enough to eat and a roof over their heads.

Figure, very very roughly, $2.50 per day as the living standard for a not-atypical human back before 1500, or, indeed 1870. Things were different for upper and middle classes, and for favored members, at least, of working classes during "efflorescences". But most humans during the long Agrarian Age lived in what the World Bank today would classify as on the edge of extreme poverty. And they did not have access to the village smartphone, or to the public health that gives our people living on $2.50/day a life expectancy at birth of 60 instead of 30.

Why were they so poor? Well, consider: in an Agrarian Age society, durable social power for women (and for men too) rests on being the mother (father) of surviving sons, themselves reproducing. But in a world of slow population growth, 1/3 of couples wind up having zero. That means that, at the margin, given that you face that 1/3 risk of ending up sonless, what do you do with extra resources? Yup. Try to have another boy. And if the average couple has 2.01 children themselves surviving to reproduce, smaller farm sizes and the greater resource scarcity that creates will eat up all of the potential higher-standard-of-living benefits from the glacially-slow Agrarian-Age growth of human technological prowess.

Before 1870, those able to attain such comforts had to do so by taking from others, rather than by finding ways to make more for everyone (especially because those specializing in producing, rather than taking, thereby become very soft and attractive targets to the specializers in taking).

This is, I think, one key difference between the old days and now. We see shadows of what we have become in the "efflorescences" of past eras, when Imperial Peace actually allowed commerce to flourish. And those times were, indeed great times for those days. But the prospects for us are so much greater.

The ice was breaking before 1870. Between 1770and 1870 technology and organization gained a step or two on fecundity. But only a step or two.

Worldwide, between 1770 and 1870, population grew by 0.55%/year and my estimate of average real income per capita grew at 0.17%/year. Using my rule-of-thumb that the value of the human deployed-ideas stock in the world economy is average income per capita times the square-root of population, that gives us a rate of growth of technological prowess of 0.44% per year over that British Industrial Revolution century