Social Theory for the Mid-21st Century: Part III. How Can the Experiences of Past Societies of Domination Be Relevant for Us?

2024 Philosophy, Politics, & Economics Society Keynote Lecture :: Westin New Orleans Hotel, New Orleans, LA :: J. Bradford DeLong :: U.C. Berkeley :: brad.delong@gmail.com :: as prepared for...

2024 Philosophy, Politics, & Economics Society Keynote Lecture :: Westin New Orleans Hotel, New Orleans, LA :: J. Bradford DeLong :: U.C. Berkeley :: brad.delong@gmail.com :: as prepared for delivery [I LIED: I don’t like the pre-delivery text enough to let it out into the wild, so I am revising the most egregious of the mind-o’s I find as I go back through it. I am dancing as fast as I can!] as revised :: 2024-11-14 Th…

From spears to steam engines: what in the experience of a society based on exploitation can illuminate the workings of a society based on technology? The interplay of power, technology, & ideology in shaping the past makes using pre-steam engine history as a potential source of illumination particularly hazardous…

III. How Can the Experiences of Past Societies of Domination Be Relevant for Us?

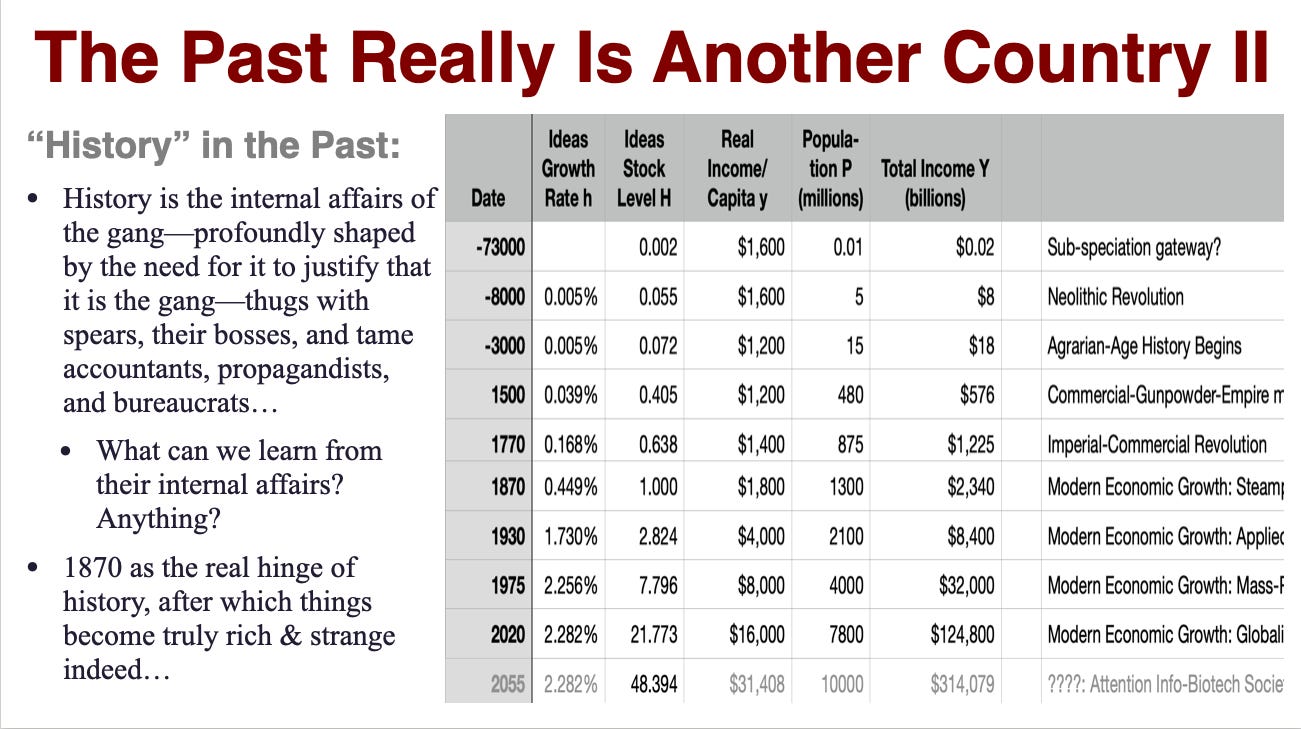

The past was very different from us in another dimension as well.

Suppose under conditions of dire Malthusian poverty you wanted to have enough for yourself and your family. You could try to invent a better mousetrap, make it, sell it, become a very productive person, and become a rich possessor of great resources as the world beat a path to your door. That was very hard back then. And what happened if you succeeded? Well, then you found yourself a very soft and attractive target for those who had chosen a different strategy.

What was that different strategy? Who were those people?

The different strategy was to focus not on becoming skilled producers of commodities but skilled practitioners of coërcive violence. Then they would say to you: give us a third of your crops, a third of your craftwork, or else. And be grateful that we leave you two-thirds if you keep your head down because you are our sheep and we want to shear you again in a year. Be grateful we do not take it all now, and that we leave you and your family alive.

These people were the gang: thugs-with-spears (and later thugs-with-gunpowder-weapons), their bosses, plus their tame accountants, propagandists, and bureaucrats, and exceptionally skilled artisans of items of war and peace who caught their eye. Looking out at you, audience, I think that had you lived in that age you, like, me would be frantically trying to sign up as one of those tame accountants, propagandists, or bureaucrats, for few among us are sufficiently gym rat-like to have done well marching the Spanish Road in the Tercio de Flandes to join the army of Alessandro di Parma. Joining that gang that runs the society of domination taking one-third of the crop and one-third of the crafts by force and fraud is about the only way to get enough.

My guess is that the relative contrast in benefits between joining the élite gang on the one hand and becoming more productive on the other is one of the things at the root of the discrepancy between the rate of technological growth now and that of previous civilizations. In all other civilizational accomplishments besides the growth of technological knowledge productive for the making of necessities and conveniences they are our equals: their art, their literature, their politics, and even their rate of advance of technologies of domination and war. But not the rate of growth of technologies of win-win productivity and coöperation.

There are, however, I guess, other reasons for why we are so blessed in terms of our rate of advance of technology.

One that I guess is absolutely key is this: The members of the élite gang neither toiled nor span, they reaped where they did not so, and they gathered where they did not scatter. But they then had to live with themselves.

We all are, as East African Plains Apes (or perhaps as cultural descendants of the Yamnaya), very sociable creatures who create and maintain our networks of solidarity via practicing gift-exchange. We want all such relationships to wind up with each of us feeling profoundly indebted to the other for all we have received. We profoundly dislike feeling that the relationship is unbalanced—that someone who should be our gift-friend has always taken, or that we have always taken from someone who should be our gift-friend. Hence ideology is needed as a psychological support—both for the victims and perpetrators of the force-and-fraud exploitation schemes of the élite gangs that run societies of domination. Sheep who are in some way soothed are easier to shear. Bandits—mobile or stationary, foreigners or local notables, individuals or state functionaries—sleep easier when they can reassure themselves at night that their victims had it coming.

Hence Aristotélēs’s declaration that while a more detailed and minute examination of the various forms of “acquisition”:

might be useful for practical purposes… to dwell long on them would be in poor taste…

Hence Seneca’s declaration, contra Posidonios of Rhodios, that:

Mechanical inventions were [not] the invention of wise men… [but] by some man whose mind was nimble and keen, but not great or exalted… [with] a bent body and… a mind whose gaze is upon the ground…

Systematic focus by those who could direct civilizational energies on technological advance was thus heavily discouraged by the psychological need for the élite to sharply degrade those from whom it took. Productive activities that did not involve the creation of necessities and conveniences that made up the plunder of the gang—painting, sculpture, architecture, literature, fine dining—these were proper ornaments for a civilization, and acceptable occupations and concerns. Public works of peace, administration, and war—these were also great. And this discouragement did not mean that commerce and industry could not flourish to some degree. Especially under the ægis of a pax imperia, commerce and the division of labor with their additions to productivity could indeed advance, in what John A. Goldstone calls an “efflorescence”, as you could produce and trade without worrying about disorganized roving and stationary bandits, but only had to keep the Big Bandit viewing you as a valuable sheep.

But there was a definite limit to how much such a civilization could progress in the way of advancing technology if it spent much energy degrading the idea that the pieces of the productive and distributive economy other than how to boss your slaves were proper concerns for a gentleman.

This character of past civilizations raises substantial problems if we attempt to appropriate their history and use it as a source of useful analogies for us and for our successors, living as we do not in societies of domination with near-static technology under conditions of dire Malthusian poverty, but rather under conditions of modern rapid technological and economic growth. The gulf between us and them is thus made remarkably large by three factors. The first is that they were societies of domination. The second is that because their technology was near-stagnant their institutions were near-static. The third is that their level of technology—of arranging things to make nature dance and humans pull together coöperatively—was so much lower than ours. All of these are stumbling blocks.

First, their status as societies of domination ruled by an élite gang. What useful analogies for 2055 can we draw from historical episodes springing from a culture where it is assumed without question that somebody with a bent back and their gaze on the ground might be clever—and probably in a cheating, dishonest, ridiculous way—but cannot be great, exalted, or indeed have any rights at all that an aristocrat need respect? What useful analogies can come from a culture where the belief that slaves should be grateful to be slaves—for, except for the accidents and injustices of history and fortune, slaves are slaves by nature—goes without question? For that was, overwhelmingly, the attitude of the élite gang.

This aspect of the gulf does indeed make it difficult and hazardous. But it does not make it impossible. The total membership of the gang of the upper class and the prosperous middle class can be large. It thus has its own internal arrangements for how it organizes itself and does its business. Yes, its business is primarily that of taking from others and then dividing the spoils. But taking is a form of “production” from the standpoint of the élite gang. Distribution is distribution. And arranging coöperation is arranging coöperation.

I think we can learn a lot in terms of useful analogies from the history of what went on within past élites. And, indeed, that is nearly all of past history that we have, at least of past written as opposed to past archeological history.

Within the élite, the ways they run their internal affairs are either better or worse, easier or harder, more vicious or less vicious.

Suppose, in one ancient society, you cross Shahanshah Khashayarsha of the Hakhamanishiya, of the Parsa—Basileus Basileōn Xerxes the Achæmenid, of the Persians—the King of Kings “Ruler of Heroes” of the Loyal-Spirit clan, of the Righteous People—by requesting that he exempt not your youngest but your eldest from the army levy. You might then find that your eldest son has been cut in two. You might find then that half of him has been placed on the left and half of them placed on the right side of the road. And Shahanshah Khashayarsha then further accomplished his purposes by making Putiya of Sfarda then watch the army march between the two halves of his dead son.

Alternatively, in another ancient society, you might have in some way crossed the politician-boss Anytos. He might then have thought to intimidate you by having Meilētos and Lykon prosecute you for impiety. You might then have expressed your contempt for the jury that found you guilty and the prosecution that has asked for the death penalty for your “crime”. You might have proposed, as an alternative punishment, that you be given the high honor free meals for life in the Prytaneîon, sitting alongside all of the city’s olympic-game champions. The jury, choosing between the two proposed punishments, might then have said “death”. But even after that you would have been allowed and strongly encouraged to flee to Thessaly before they come around with the deadly hemlock for you to drink. And they might then be taken somewhat aback at your actions: that Sokrates chose to die at the age of 70 in order to make points about justice and fairness and reason.

The land empire run by the Parsa Hakhsamanishya clan and the seaborne empire run as the demokratia of the Athenai handled their dissenters in very different ways. Comparing and contrasting their intra-élite human affairs with each other and with ours could be a very fruitful source of historical examples and social theories relevant to us and to 2055. But always remember that the élite society’s internal workings cannot but be profoundly affected by the fact that it is, at bottom, an extortion gang ruling over a mass population of slaves or near-slaves. Aristoteles thought that it would always be such—that civilization was only possible when there was a class that had enough, and thus had enough leisure to think, but that was impossible unless in some way we could have the miracles in which:

every instrument, at command, or from a preconception of its master's will, could accomplish its work (as the story goes of the [robot blacksmith] statues of Daeidalos; or what the poet tells us of the [self-propelled catering-cart] tripods of Hephaistos, “that they moved of their own accord into the assembly of the gods”), the shuttle would then weave, and the lyre play of itself; nor [then] would the architect want servants, or the master slaves…

But we do have such miracles. And our possibilities for the self organization of humanity as an anthology intelligence in our day should profit thereby.

The second stumbling block to using theory based on analogies from the distant past is that back in their day because their technology was near-stagnant their institutions were near-static.

For us, Schumpeterian creative destruction is a thing: every generation since 1870 human technological competence has more than doubled. And the “destruction” aspect is very real: every generation tasks, jobs, occupations and professions, livelihoods, industries, sectors, communities, and regions have found themselves in its bullseye. This has been the case since late-1700s England. There and then the “poor stockingers” found that their skilled profession was no longer needed because of improvements in knitting technology, and that even though they had Acts of Parliament setting out for them and their employers their standard conditions of work and pay, those Acts could and would be repealed or ignored because there was enough money to be made by allowing the forward march of knitting technology. The march of technology had given to them 200 years ago, creating the stocking-frame that allowed for a large enough fall in the price of stockings for there to be a mammoth boost in demand as they became middle-class conveniences rather than pure upper-class luxuries. But in the late 1700s the march of technology taketh away. And General Ned Ludd could not help them.

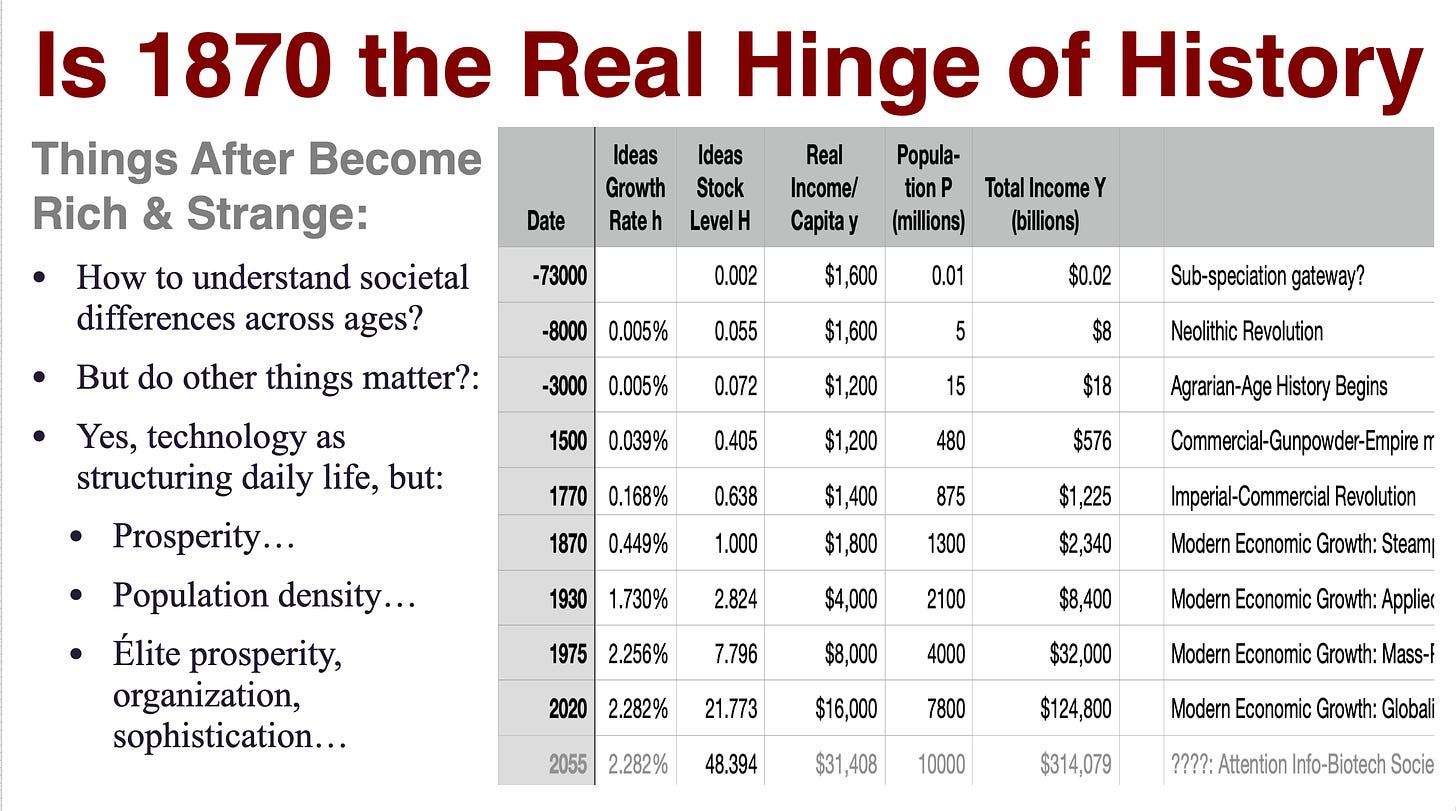

This type of technocrisis was not something any society before ours ever had to deal with. And even where Schumpeterian creative-destruction is overwhelmingly creative, it is still change. And change has to be managed—again, something with no close analogue before. No history of any time before the invention lf the steam engine can help us here: no useful analogies can be found. As the underlying techno-economic foundational hardware of their societies changed, they did indeed have to rewrite the socio-econo-political-cultural societal software of human interaction patterns that runs on top of the hardware so that things would not crash, or at least not crash often. But this was a process of slow, if bumpy, adjustment. Our quantitative index H of technological prowess is indeed 2.5 times as large in the year -500 of Classical Antiquity as it had been in the year -3000 at the dawn of the Bronze-and-Writing Age, and still 2.5 times higher in the year 1500 at the dawn of the Imperial-Commercial Age. But the first took 2500 years and the second 2000. We cover the same amount of apparent transformation in 40 years. and then we do it again. General Ned Ludd could not help the poor stockinger. And no past historical examples can help us deal with the types of problems that brought him to the forefront.

The third stumbling block is that the pre-Modern Economic Growth level of technology—of arranging things to make nature dance and humans pull together coöperatively—was so absurdly much lower than ours. Most of what we call “work” would be close to incomprehensible to people in previous centuries. And many of the institutional pattern of exchange and direction would leave them similarly flummoxed.

As for myself, I am flummoxed by the extraordinary differences in prosperity and in the pace of technological progress. I am thus truly convinced that 1870 is the real hinge of history. After it, from the perspective of all previous history, things become truly rich and strange.

So how then would we start constructing a social theory based to any substantial degree on pre-1970 history to help us in 2055? How to understand societal differences across ages? We understand that technology is structuring daily life. And we understand that as technology changes, daily life changes. And we understand that daily life shapes people's ideas of how things should, must, ought to be. Perhaps something can be learned from intra-élite affairs. But perhaps the ultimate lesson from our history is that we and those in our future ought not to think we must operate under the constraints that they were under, because we do not have to.

References:

Aristoteles. 1946 [-86]. Politics. Ed. Andronicos of Rhodios. Trans. Ernest Barker. Oxford: Clarendon Press. <https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.50166/>.

Bacon, Francis. [1627]. The New Atlantis. New York: W.J. Black. <https://archive.org/details/essaysnewatlanti00baco>.

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2024. “The Poor Stockinger”. In What Rough Beast?: The 21st-Century World in Political-Economy Polycrisis. Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality. July 17. <https://braddelong.substack.com/p/21-the-poor-stockinger-what-rough>.

Herodotos. 1858 [-420]. The History of Herodotus. Trans. George Rawlinson. London: John Murray. <https://archive.org/details/historiesofherod00hero>.

Mauss, Marcel. 1954. The Gift: Forms & Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. Trans. Ian Cunnison. London: Cohen & West. <https://archive.org/details/giftformsfunctio00maus>.

Platon. 1897. Apology, Crito, & Phaedo of Sokrates. Trans. Henry Cary. Philadelphia: David McKay. <https://archive.org/details/platosapologycr00broogoog>.

Seneca Minor, L. Annæus. 1917 [64]. “On the Part Played by Philosophy in the Progress of Man”. Moral Letters to Lucilius,. Trans. Richard Gummere. London: William Heinemann. 90. <https://archive.org/details/adluciliumepistu01seneuoft>.

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…

History demonstrates that hierarchical polities and the periodic outbreaks of what we would now call true Communison occur. Hierarchies of whatever stripe end up wanting to take more than the producers want or can give. Disfatisfaction with the elites results in various revolts and the desire for a more equal society, so that it is more like "win-win" for the majority. The C20th saw both monarchies, dictatorships as hierarchical and extractive/parasitical, as well as commutarian (e.g. USSR, PRC).

But our genes were honed in deep time for social hierarchies, so the wolves would always find way to exploit the sheep and recreate hierarchical societies.

Has this dynamic changed at all? I don't think so.

Has the reduced scarcity of necessities and rapid technological advance changed the dynamic? To some extent. Just as "new" technologies combine older technologies, so that they proliferate through machine diversity (the equivalent of biological radiation of species), so do the number of niches associated with that diversity.Societies can fragment into groupings around particular technologies and eke out existence that for some become very lucrative, and even difficult to steal from.

However, that diversity makes it very difficult to solve and agree actions that would be good for all groups. Hence we cannot solve nuclear weapon proliferation and global heating to name just 2. This will lead to destruction, a winnowing of the global population, and even, in extremis, eventual extinction.

We are at a potential fork in the road. Either assert the "dominant society" approach that leads to conflict, or find a solution that ensures cooperation and action to ensure all the diverse groups can live with. We have tried with the League of Nations, the United Nations, many international institutions, all of which have failed to reach truly equitable results. Either we solve the cooperation problem, or...

Is not the social theory that is presented excessively influenced by the technological determinism of Marx and Engels? The Chinese invented gunpowder and the compass centuries before they were ‘re-invented’ in Europe, but no age of gunpowder and transoceanic conquest came from China. This suggest a degree of autonomy of the social-political order from its underlying technological basis that is (much) larger than the narrative seems to allow.

In extrapolating the future of the world economy you seem to ignore a recent development that is truly unprecedented in human history, namely, demographic depression unrelated to catastrophic events. This should have also implications for the pace of technological development, also bearing in mind that, to put it mildly, even in modern times not all societies have proven equally adept at promoting technological progress and technology adoption.