Social Theory for the Mid-21st Century: Part II. From -73000 to 2055: Malthusian Poverty to Modern Economic Growth

2024 Philosophy, Politics, & Economics Society Keynote Lecture :: Westin New Orleans Hotel, New Orleans, LA :: J. Bradford DeLong :: U.C. Berkeley :: brad.delong@gmail.com :: as prepared for...

2024 Philosophy, Politics, & Economics Society Keynote Lecture :: Westin New Orleans Hotel, New Orleans, LA :: J. Bradford DeLong :: U.C. Berkeley :: brad.delong@gmail.com :: as prepared for delivery [I LIED: I don’t like the pre-delivery text enough to let it out into the wild, so I am revising the most egregious of the mind-os I find as I go back through it. I am dancing as fast as I can!] as revised :: 2024-11-14 Th…

Imagine standing in 1905, looking back at ancient agrarian poverty in the year -3095 at the start of the Bronze Age, then peering ahead to 2055—and recognizing that the rough proportional difference in human technological mastery across the first 5000 years is the same as over the next 150. To call technoeconomic change in the past 150 years truly seismic is to massively undersell it. It is very likely that the magnitude of that shift is the most important thing from which to start deriving lessons from and of history…

II. From -73000 to 2055: Malthusian Poverty to Modern Economic Growth:

How, then, are we today to think about the world as it will be 2055?

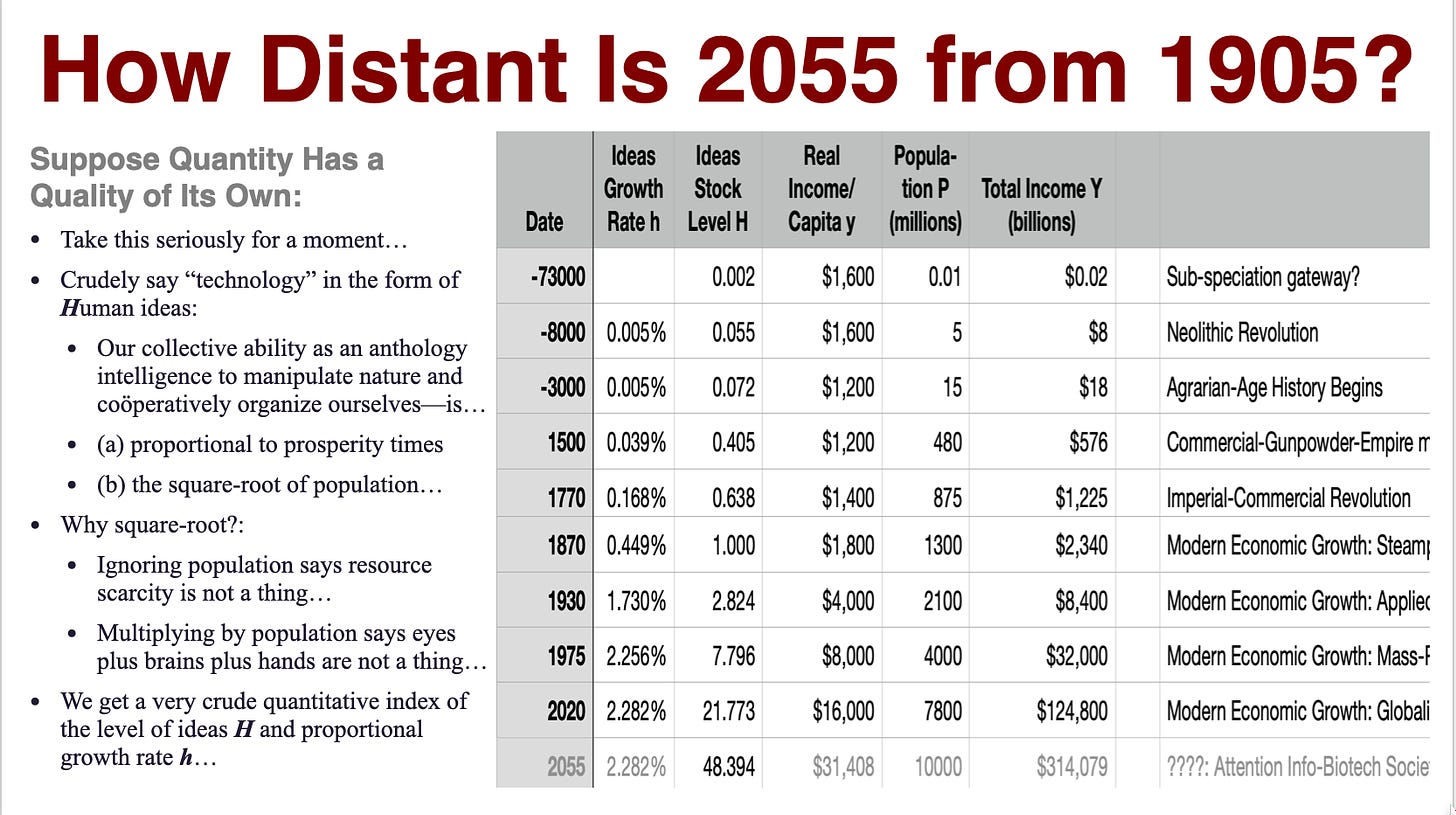

2055 is far from today, and is much farther from the 1905 that I think is still the focal point of what American academia teaches and thinks about. How far is it? I am going to claim that 2055 is as far from 1905 as 1905 is from the year -3000.

Let me now try to justify this very large and unsettling claim.

We have knowledge about human population and prosperity today: total world gross product of $130 trillion a year, a human population of 8 billion, and thus an average—but extraordinarily unequally distributed—income per capita of $16,000 per year.

We have guesses about human populations earlier, informed guesses but guesses. And we have guesses about prosperity—or rather its lack—in the pre-1500 and before world, largely Malthusian as it was, back in the days when the overwhelming bulk of the people were working class between 30 and 80% of working class resources had to be spent for bare necessities. By “bare necessities” I mean enough shelter that you don’t spend two hours a day worrying about how wet you are, enough clothing you don’t spend three hours a day worrying about how cold you are, plus your 2000 calories a day so you don't spend four hours a day unable to think about anything other than how hungry you are; the world in which the typical woman undergoes eight pregnancies, yet population growth averages 2.5% per generation—so that those eight pregnancies yield only 2.05 people who themselves survive to reproduce, weith rates of pre-birth, stillbirth, miscarriage, and then infant and child that horrify us.

The world as a whole is much, much better off today than it was back in the day, in terms of our ability to command nature and to coöperatively and productively organize ourselves. Less than 5% of us today who have a standard of living within shouting distance of what was the typical working class standard of living back before 1500. Even those 400 million have access to modern public health, which has driven infant mortality down to what earlier societies would have regarded as absolutely god-blessed levels. Those 400 million also have access to the village cell phone and the knowledge it can transmit.

We are today so much richer than people were in 1500 and before. But how much? What happens when we quantify this?

It turns out that it is surprisingly difficult to make solid the quantification of how much richer we are than people were in the past. I like to think of this in the context of James I and VI and The Scottish Play—Macbeth—that he semi-commissioned.

Suppose you want to watch MacBeth in your own house, or in your hotel room, tonight. No problem. You have a choice of 20 versions. You might get dinged for $3.99, the same share of average income today $0.20 back then would have been. You might not—it might only cost you pennies for electricity.

Suppose you want to watch MacBeth in your own house in the year 1606. Well, you had better:

be named James Stuart.

be the principal occupant of Whitehall Palace.

have $5,000 of today's values of loose coin to finance it, even given the very low real wage levels back then.

have Shakespeare's Company of Actors on retainer

have thought of it a month ago so that The Kings’ Men Players would have time to put it in repertory.

In either case you have the experience of watching MacBeth—of having the experience that evokes pity and terror and that both entertains and informs, in a way that rich people in earlier civilizations were willing to pay a fortune for. But for us it costs 1/40000 as much. And there is an enormous gain in flexibility because you did not have to plan to do this a month beforehand.

On the other hand, if I wanted to watch a professional live theatrical performance of MacBeth, it would cost me $100. You can bet that there were 50 or so people crowding into Whitehall Palace when Shakespeare's company put on MacBeth, even in a private show for King James I and VI of England and Scotland. From that perspective, the real price of watching Macbeth live has not in fact declined. Besides, they got to see Shakespeare in person.

The first of these points suggests that standard calculations are a massive understatement. They say that we today are, maybe,13 times as rich as humanity was on average back before 1500. But buy there has since 1606 a 40,000-fold fall in the real price of getting all pity and terror and catharsis and entertainment and insight into the human condition you get from MacBeth, and you have to conclude that any accurate quantitative metric would show a difference much more than 13-fold.

But the second suggests, to the extent that it leads to the conclusion that things are less important while relationships between people are key, that the differences between us and them are not, in fact, worth so much.

I am on the side of the first. But I see these as knotty problems with no good and solid resolutions. Personally, I think this Gordian Knot can be cut only if I make precise distinctions between wealth, utility, and eudaimonia that economists are the most ill-equipped people in the world to ever possibly make. So what I really want to do is to throw questions of the proper measurement of economic growth questions over the wall for you to deal with.

However, for the purpose of this talk, I take the economists' numbers seriously. And I also take seriously the idea that perhaps a sufficient difference in quantity has a difference of quality of its own.

So take our numbers on human population and human prosperity. Use them to construct a crude quantitative index of human technology—the value of the stock of ideas deployed across the human race with respect to our ability as an anthology intelligence to manipulate nature to our purposes and productively and coöperatively organize ourselves to pursue our goals.

Let me assert, uncontroversially, that this quantitative index should be proportional to our prosperity in terms of valuable things we can create and utilize: that is just a normalization.

Let me assert, more controversially, that this quantitative index should be prosperity multiplied by the the square root of the human population. Why the square root? If we ignore population entirely and just say technology is proportional to prosperity, we are saying that resource scarcity is not a thing—that it requires no greater level of human competence and command over nature and ability to organize to support our 8 billion people at our current level of prosperity than it would to support 400 million people. That cannot be right. Resource scarcity is a thing.

On the other hand, taking technology to be equal to multiplying prosperity by population implicitly says that eyes plus brains plus hands are not a thing, that the only thing that is valuable is the ideas and the brains of humanity as an anthology intelligence and not individual workers. That also cannot be right. Individual human productivity is a thing.

Square root is a compromise in the middle. And if you have a better idea I would love to adopt it as an alternative to what we have.

So we get a very crude quantitative index, which I call big H, of the level of the value of the stock of Human ideas deployed across the world. And we also get this proportional growth rate, little h, of our technology. I propose to take this seriously.

When we take this seriously, we see the past really is another country, and a very different country. It is so much more another country that the differences between then and now are ones so great that Silicon Valley TechBros currently raving about forthcoming “singularities” when they will have succeeded in building and then worshipping machines made of stone that think with AGI would have a difficult time wrapping their heads around their magnitude.

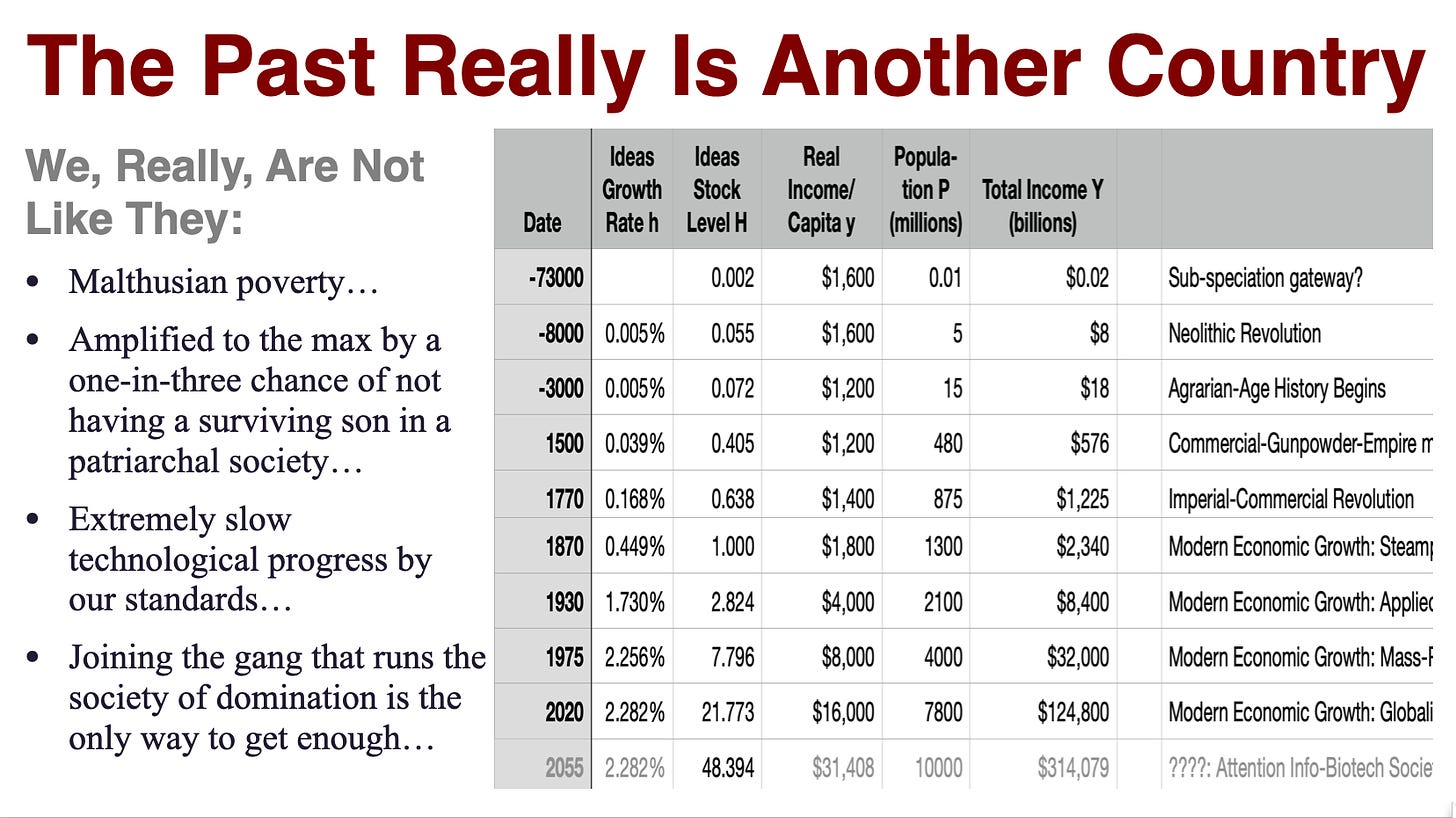

We see a past of everywhere before 1500—and note, in many parts of the world long after that—characterized by three salient features:

Malthusian dire poverty.

Extremely low technology relative to us.

Exceedingly slow rates of growth of technology relative to us.

We see Malthusian dire poverty. Our guesses set typical world incomes before 1500 during the long Agrarian Age at around $1200 per capita per year. At that level of poverty the risks, unless you are part of an élite, that you will go very hungry sometime next week and die of famine sometime in the next decade are not things you dare ignore. You see the typical woman among you having eight pregnancies, yet raising only 2.05 children on average to survive to reproduce in the next generation. You see the typical woman who happens to survive to late middle age as having one chance in three of not having a surviving son—which means that, in heavily patriarchal societies, she needs a son-in-law who really likes her to an unusual degree, or she may well face very significant sociological trouble. Hence where there are extra resources families are pushed to try to have more children, to try to buy more insurance against her being left alone in a patriarchal society.

We see extraordinarily low levels of technology compared to our standards. Compared to our H(today) = 23 and H(1870) = 1, we have H(1500) = 0.4 and H(-3000) = 0.07. The powers of the anthology intelligence that is humanity are, in comparison, truly godlike. Óðinn had a spear, Gungnir, unstoppable, fatal, and inerrant; and had two ravens, Huginn and Muninn, who whispered in his ear the news from places far out of his sight. Þórr had a magic hammer, Mjǫllnir, that struck anywhere within his eyesight with the force of a lightning bolt, and then returned to his hand so he could strike with it again. (He also had a two-wheeled cart drawn by two magic self-reviving goats, Tanngnjóstr and Tanngrisnir, who could provide a feast one night and yet be ready to pull the cart the following morning; but the cart was so underlubricated that the noises it made as it bumped along the skyways were the thunder.) Compared to what we can and do accomplish for good and for ill, they were helpless and hapless.

We also see extremely slow technological progress by our standards. From the invention of writing and bronze around -3000 to the 1500 start of the transition from the Agrarian Age to Commercial-Imperial Society, the average annual proportional rate of increase h of the technology of humanity as an anthology intelligence was only 0.04% per year: 50% per millennium. We see more proportional technological change than that each and every generation, and have since 1870 or so. That is also an extraordinary difference.

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…

Just one small comment on the paragraph directed to the audience: "Personally, I think this Gordian Knot can be cut only if I make precise distinctions between wealth, utility, and eudaimonia that economists are the most ill-equipped people in the world to ever possibly make."

I think it needs to be kept in mind that economists were not ill-equipped to make these distinctions right up to WWII. Keynes was well versed in ethics and could therefore write "Economic prospects for our Grandchildren" which, as you know, addresses your question directly. He also insisted economics is and should remain a moral science. Less well-known is Frank Knight's writings in ethics, such as "Ethics and the Economic Interpretation" and "The Ethics of Competition." It is really only Friedman's highly influential "The Methodology of Positive Economics (1953)" that allows mainstream economics as a discipline to abandon competency in ethics and largely abandon interest in the social, political, and behavioral reality of its assumptions/models. Schumpeter had already understood this to be the "Ricardian Fallacy." Sen's aptly titled "Ethics and Economics" ably recounts the basic story. Note that Sen also faults philosophy for throwing economic questions over the wall to economists.

Economists are one of the few disciplines that does a great job looking at the near- and mid-past and reporting on what a drag race of productivity gains, capital accumulation, and improved living standards humanity has seen. What a very different perspective than most of humanity, where decision-making and opinions are often based on the past 6 months. [Am I cynical yet? Debate is welcome!]