Some Comments on þe ¶s of “Slouching Towards Utopia” Þt Discuss þe World’s 2.1%/Year Post-1870 Average Proportional Technology Growth Rate, &

BRIEFLY NOTED: For 2022-06-24 Fr

FIRST: Some Comments on the ¶s of “Slouching Towards Utopia” That Discuss the World’s 2.1%/Year Post-1870 Average Proportional Technology Growth Rate

[The 2.1 percent per year average annual worldwide technology growth rate starting in 1870] meant that the technological and productivity economic underpinnings of human society in 1903 were profoundly different from those of 1870—underpinnings of industry and globalization as opposed to ones that were still agrarian and landlord-dominated. The mass-production underpinnings of 1936, at least in the industrial core of the global north, were profoundly different also. But the change to the mass consumption-suburbanization underpinnings of 1969 was as profound, and that was followed by the shift to the information-age microelectronic-based underpinnings of 2002. A revolutionized economy every generation cannot but revolutionize society and politics, and a government trying to cope with such repeated revolutions cannot help but be greatly stressed in its attempts to manage and provide for its people in the storms.

Let me stress this: humanity had never before seen anything like this pace of economic transformation. Not just production, but newly-transformed production and the further transformation of production became the principal work-life business of humanity. As much economic change and creative destruction as had taken place over 1720-1870 took place every 33 years after 1870. And the pace of change over 1720-1870 had already been more than fast enough to shake societies and polities to pieces. "All that is solid melts into air", Marx and Engels had written in 1848: all established hierarchies and orders are steamed away. And they had no real idea what was coming: the pace of worldwide change of their day was less than 1/4 of what it would become after 1870.

Much good, but much ill also flowed [from the creative-destruction well-nigh complete revolutionizing of the economy every generation post-1870]: people can and do use technologies—both the harder ones, for manipulating nature, and the softer ones, for organizing humans—to exploit, to dominate, and to tyrannize. And the long twentieth century saw the worst and most bloodthirsty tyrannies that we know of.

More of a proportional increase in humanity's deployed technological prowess every 23 years after 1870 than was seen in the entire 1770-1870 Industrial Revolution century. (And more than in the entire 1500-1770 Imperial-Commercial Revolution Age. And more than over all of 800-1500.) These repeated generation-after-generation technological shifts upended and revolutionized economies. The associated repeated creative destruction upended societies as well. This posed two problems for governments: How were they to deal with the "destructive" part of creative destruction as it upended the lives of their people? And how were they to deal with neighboring governments that decided to use enhanced technological powers for evil for destruction and oppression? At the sharp end, a government gone horribly wrong was a genocide-scale problem for the people under its boot, and for the people who were that government's neighbors. The 20th century saw the worst tyrannies ever.

All that was solid melted into air—or rather, all established orders and patterns were steamed away. Only a small proportion of economic life could be carried out, and was carried out, in 2010 the same way it had been in 1870. And even the portion that was the same was different; even if you were doing the same tasks that your predecessors had done back in 1870, and doing them in the same places, others would pay much less of the worth of their labor-time for what you did or made. As nearly everything economic was transformed and transformed again—as the economy was revolutionized in every generation, at least in those places on the earth that were lucky enough to be the growth poles—those changes shaped and transformed nearly everything sociological, political, and cultural.

The wave of technological progress at an unprecedented pace—one that puts even the 1770-1870 Industrial Revolution Century to shame, and that packs as much into one year as we saw in 50 pre-1500 years—and the associated creative-destruction wealth-generating process of repeated revolutionizing and transformation of the economy is THE central underlying process of 20th-century history.

All else has to adapt, or fail to adapt, to that. And all else did—or failed to do so.

And it was not just that there was one techno-economic revolution between 1870 and 2010. There were at least four: from largely-agrarian to global-industrial economy, from global-industrial to mass-production economy, from mass-production to high mass-consumption economy, and from high mass-consumption to information economy.

That is why the history of the 20th century took the form that it did.

Contrast this with the way that history used to be, back when economic changes were only important in what Fernand Braudel and company liked to call la longue durée, and economic structures were merely the painted backdrop before which, or at most the furniture around which, the play of history proceeded.

Before 1770 certainly, and before 1870 mostly, history is, you know, history: kings, prophets, generals, soldiers, artists, thinkers, sometimes merchants—with the occasional suppressed peasant revolt. The economic is not really a character.

Why not? Because two things are going on that largely offset each other. Technology is advancing. The human population is growing, and so the average farm size is shrinking. From, say, -8000, when we first got farms, up until 1500 everywhere and 1870 in most places and 1980 in rural China and India, the second counterbalanced the first, with the result being that the typical human living standard altered little. Yes, empires and cultural networks grew bigger and more sophisticated across centuries and millennia. Yes, the upper classes lived better and better. But even those structural trends took centuries if not millennia to become visible. Why? Because the rate of technological progress was so damn slow. Think, before 1500, of technology as improving by 5% in a century. Think, between 1500 and 1770, of technology improving by 15% over a century. Even between 1770 and 1870, the deployed level of technology increased by only 50% worldwide.

The structure of the economy mattered for history. But economic changes did not. They simply were not big enough.

As Oded Galor puts it, if you took someone from Jerusalem in the year -800 or 50 or 1500 or 1800, and then dropped them in Jerusalem in any one of the other three years, most of what was going on would be comprehensible. Take someone from any of those years—even 1800—and drop them in Jerusalem today, and most of what was going on would be very strange indeed. In terms of my technology index, that is the difference between the 0.16 of the year -800 or the 0.24 of the year or the 0.43 of 1500 or the 0.7 of 1800 on the one hand, and the index value of 25 today.

One Video:

Milton Friedman & Samuel Bowles (1990): Debate <https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=9w9ymJm7XVk>:

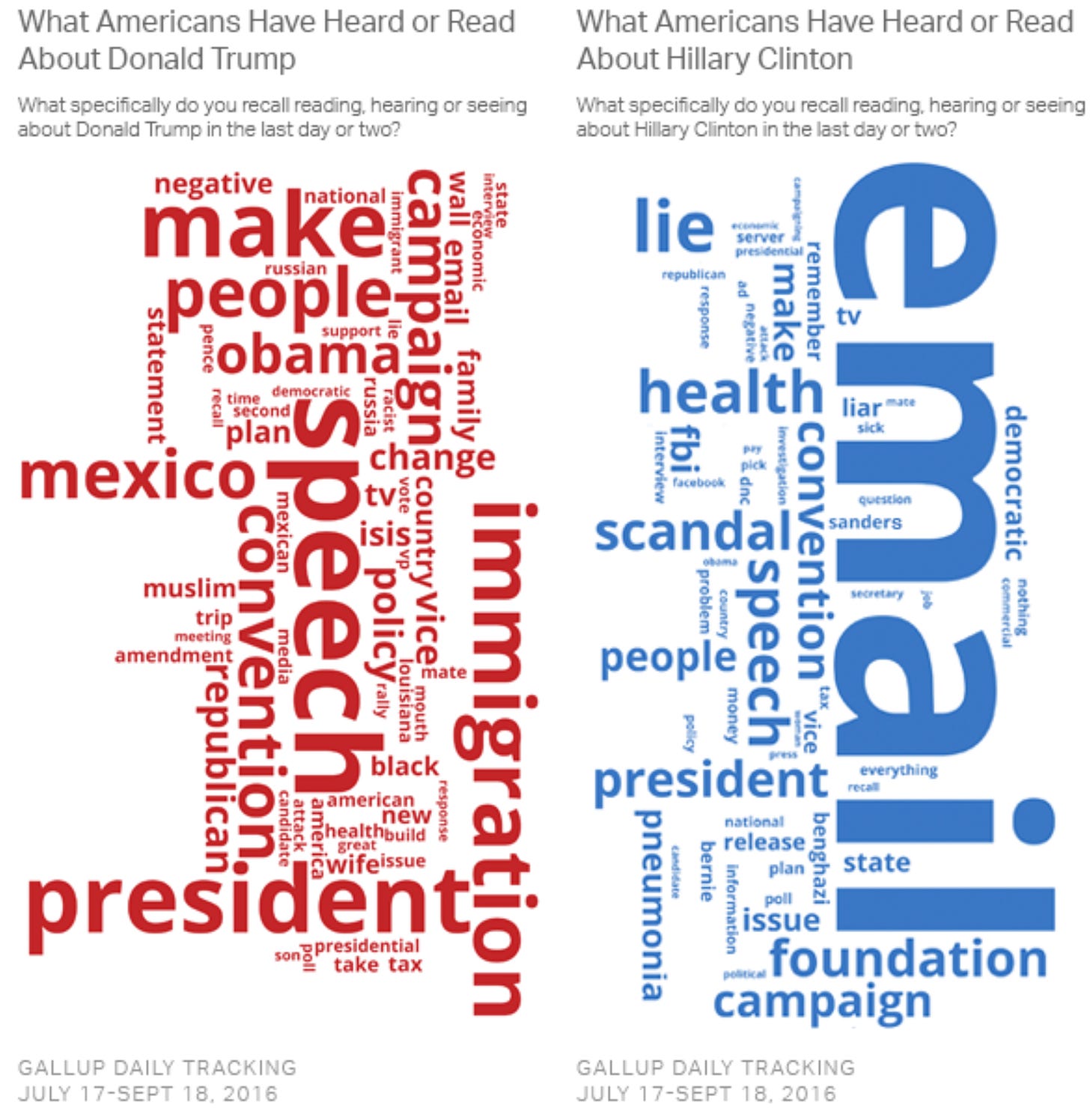

One Image:

Very Briefly Noted:

Jeff Schechtman & Brad DeLong: It’s Always All About the Economy: ’Amid the unprecedented turmoil of today’s political climate, the mantra that Bill Clinton reportedly embraced during his winning presidential campaign in 1992 still holds: “It’s the economy, stupid.” On this week’s WhoWhatWhy podcast, we talk with economist Brad DeLong… <https://whowhatwhy.org/economy/its-always-all-about-the-economy/>

John Fernald & al.: Dale Jorgenson: Investment, Growth Accounting, & Economic Measurement: ‘It was with deep sadness that we learned that Dale Jorgenson had died on 8 June 2022 at the age of 89. He was an intellectual giant whose contributions to economics were broad and deep… <https://voxeu.org/article/dale-jorgenson-investment-growth-accounting-and-economic-measurement>

Jon Emont: How Singapore Got Its Manufacturing Mojo Back: ‘The city-state courted highly automated production lines to become a rare wealthy country to reverse its factory downturn… <https://www.wsj.com/articles/singapore-manufacturing-factory-automation-11655488002>

Annabelle Timsit: Elon Musk Calls Tesla Electric Car Factories ‘Gigantic Money Furnaces’ <https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/06/23/elon-musk-tesla-factories-gigantic-money-furnaces/>

Bharath Ramsundar (2016): The Ferocious Complexity Of The Cell <https://rbharath.github.io/the-ferocious-complexity-of-the-cell/>

Twitter & ‘Stack:

Daniel Laurison &Anne Helen Petersen: Why Don’t Politicos Look Like the Rest of Us?

Noah Smith: Central Bank Digital Currencies Are Not Very Interesting or Useful: ‘Why a CBDC is (probably) just a payments app…

Bill Tschumy: ‘Just finished reading The New Climate War by Michael E. Mann. Fascinating book. I was slipping into climate doomism myself, but Mann’s balanced treatment of the subject pulled me back from the brink… <

Nowhere Girl: ‘It’s bizarre when “rationalists” who live in fear of Roko’s Basilisk and shit are jerks to trans people because they think we should just look at our genitals and conclude we’re “wrong” when that’s not how the process of identity formation works…

Thomas Levenson: ‘Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett are fruit from a poisoned tree. Pass it on…

Nadezhda: ‘While you’re listing excellent blogs with a lively community, I’d include Obsidian Wings and the sane voice of the irreplaceable Hilzoy…

Timothy Burke: The Read: Daniel Laurison, Producing Politics