SUBSCRIBERS ONLY: Does Not þe U.S. Government Right Now Have a Free Lunch Before It, via Debt Issue, as Long as g > r?

Are our economic models intuition pumps, or filing systems? Not-yet-ready-for-primetime thoughts...

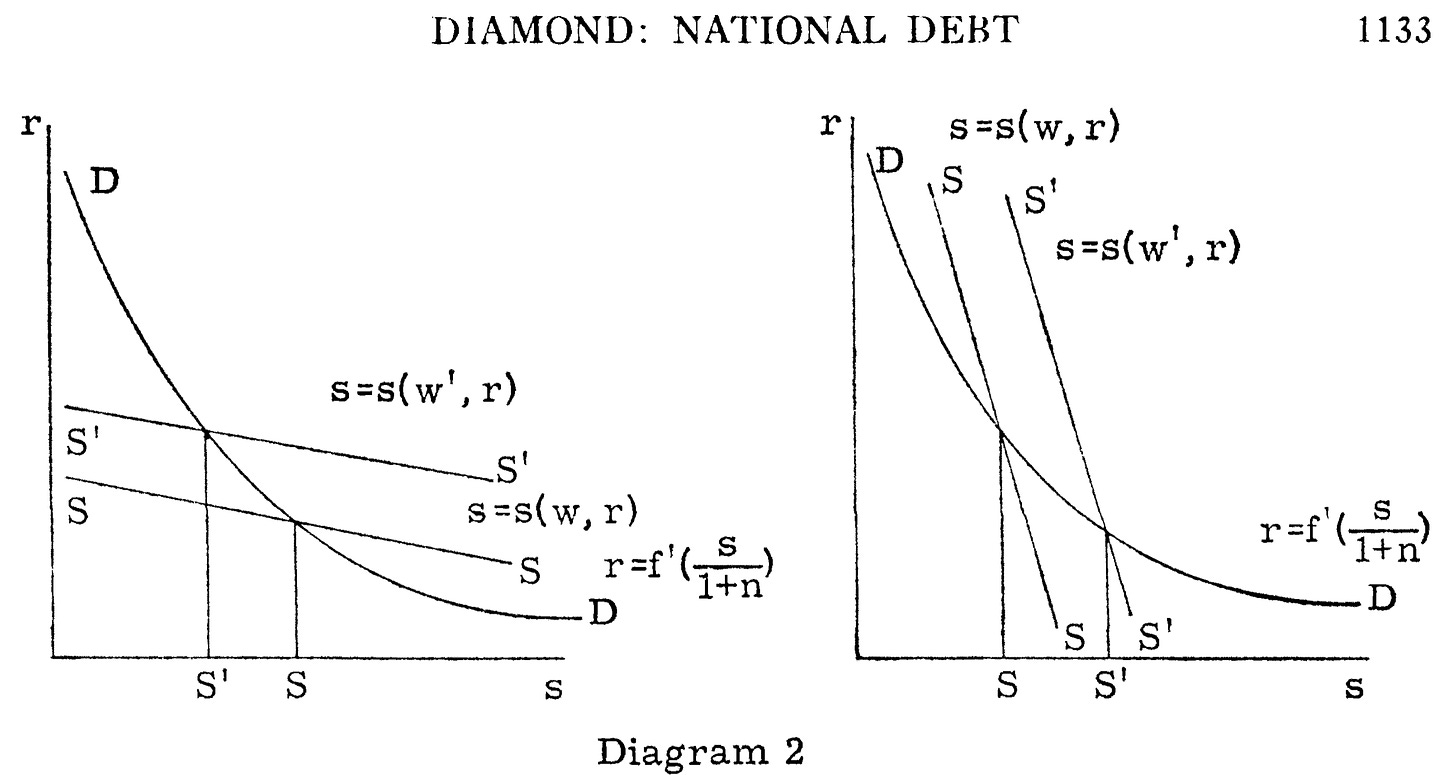

One of our standard workhorse models—the Diamond OLG model, the one I learned in the second week of my first class from Olivier Blanchard—says this:

Suppose the real interest rate on government debt r is less than the proportional rate of growth of per capita income g (or, possibly, g+n, the sum of that growth rate g and the population growth rate n—it depends on your view of equity across generations and with respect to immigrants).

Then the economy lacks sufficient safe assets with which to transfer wealth securely from the present into the future.

And then there is no cost to government borrowing: rather than government borrowing being something that requires a government to offer value to its counterparties and thus draining resources for other uses, keeping its counterparties’ wealth safe is something the counterparties are willing to pay for, and is a profit center for the government, increasing the resources that it can use for other purposes.

The immediate and powerful implication is that there is a free lunch for the government to grasp by issuing debt, and continuing to issue debt unless and until such debt issue raises the real interest rate r on government securities up to the growth rate of per capita income (and perhaps the sum of that rate and the population growth rate).

Now there is the question of how the government should use the resources it gains by keeping its counterparties’ wealth safe. And there is the question of what steps the government should take to guard against risks that the situation might change. Those are important questions. But they do not overturn the basic result. Any use of the resources at all will leave societal well-being enhanced. The risks are not real downside risks: they are—unless the government messes up massively—are not proper downside risks, but only the risk that a good thing, a free lunch opportunity, will come to an end. And a government that finds a way to mess up massively is likely to do so: refusing to eat a free lunch in order to keep the messing from taking one particular form does not seem to me to be very wise.

When the real interest rate on government debt is less than the income growth rate, the government is in the position of the Renaissance Medici Bank. The Medici Bank did not pay interest to depositors in return for the loan of their purchasing power today; the Medici Bank charged fees to its counterparties for performing the service of keeping their wealth safe and accessible.

What the human psychology is and how institutions have evolved in such a way as to get us into this situation in which government borrowing is not a cost but a profit center—that is a very interesting and knotty question. But we are here. And our standard workhorse model is unambiguous: there is a free lunch by grasp by running up the government’s debt and then using the social power over resources thus transferred to the government to do useful things. What are the best useful things to do—let us have that discussion. The government could pay to build useful things. The government could finance private corporations by buying their stock. The government could simply send out checks to people in general. I favor the first. But let us recognize that this is a political discussion, and that all 50 Democratic and Independent (and perhaps 10 Republican) senators have to sign on, or else the free lunch will be wasted.

How to guard against risk—let us have that discussion too. However, I see very little in the way of risk to be guarded against. The risk—that is not really a downside, but rather the going-away of an opportunity—is that interest rates will rise so that, when it comes time for the debt to be rolled over, the terms on offer are not favorable. The obvious way to manage that risk is to raise taxes and so reduce the market float of government debt to the appropriate, manageable level. These taxes can be raised from the economy as a whole. These taxes can be raised from high rollers—primarily those who benefitted from the massive asset price increases that accompanied the coming of this g > r. Or taxes can be raised indirectly, using regulatory tools to require that financial institutions that benefit from the government’s provision of deposit insurance and of a financial lender-of-last-resort in financial crises hold whatever amount of government debt seems optimal. This would not be in any way inequitable: finance has never paid for the lender-of-last-resort function, and has paid much less than the value of deposit-insurance guarantees, from both of which it has profited immensely. Such holding requirements are not an institutional innovation: this was a large chunk of how President Abraham Lincoln and Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase financed the Union Army during the Civil War. It is not a new or an untried or a norm-breaking policy move.

Any questions?

Yes, I see a hand in the back…

You are saying that I am using the Diamond model as an intuition pump, applying it to a new and strange situation that we did not think we would get to? And that this is wrong? You are saying that economists’ models are not intuition pumps but filing systems? Convenient ways of keeping track of experiential knowledge? And when the conclusions of models run counter to the judgments of the great and the good, we should turn to other models? And that the great and good are now judging that we have already run up the debt too far?

Perhaps…

But this is not using the Diamond model as very much of an intuition pump. Market economies work, when they do, because they provide people with incentives to create very useful and valuable things. Right now, with g > r, government debt is incredibly useful and valuable. And the government can easily create it. So why not respond to the signals the market is sending—nay, yelling and screaming at us—and act accordingly?

Let me, however, on the other side, set forth a quote from John Maynard Keynes:

John Maynard Keynes (1936): The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money: Chapter 12. The State of Long-Term Expectation: ‘Enterprise.... Only a little more than an expedition to the South Pole, is it based on an exact calculation of benefits to come. Thus if the animal spirits are dimmed and the spontaneous optimism falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die....

This means... that economic prosperity is excessively dependent on a political and social atmosphere which is congenial to the average business man. If the fear of a Labour Government or a New Deal depresses enterprise, this need not be the result either of a reasonable calculation or of a plot with political intent;—it is the mere consequence of upsetting the delicate balance of spontaneous optimism.

In estimating the prospects of investment, we must have regard, therefore, to the nerves and hysteria and even the digestions and reactions to the weather of those upon whose spontaneous activity it largely depends...

LINK: <https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/economics/keynes/general-theory/ch12.htm>

References:

Dean Baker, J. Bradford DeLong, & Paul Krugman (2005): Asset Returns and Economic Growth <https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2005/01/2005a_bpea_baker.pdf>

J. Bradford DeLong (2018): Economists' Models: Analysis Pumps or Filing Systems? And Do Countries with Reserve Currencies Need to Fear Solvency Crises? <https://www.bradford-delong.com/2018/11/economists-models-analysis-pumps-or-filing-systems-and-do-countries-with-reserve-currencies-need-to-fear-solvency-crises.html>

Peter Diamond (1965) National Debt in a Neoclassical Growth Model <https://www.aeaweb.org/aer/top20/55.5.1126-1150.pdf>

John Maynard Keynes (1936): The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money: Chapter 12. The State of Long-Term Expectation <https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/economics/keynes/general-theory/ch12.htm>

1275 words

The use of graphs without defined coordinates is not tolerated very well in my field (physical chemistry.) What is the horizontal axis of the figure? is the first questionIi'd get if I put something like this up for nonspecialists. Or a class.

I hope you are right. But, a couple of concerns arise. Aren't the payments to individuals and families in upper-income brackets fueling an inflation of stock market values (since these people do not need to spend their payments, they can and do invest them in stocks)? And doesn't this lead to a higher likelihood of a damaging financial system crash? Finally, won't any attempt to raise taxes, especially in 2021 or 2022, play right into the hands of the GOP who will frame it as an attack on business and families (if a wealth tax) and everyone (if an income tax)? I.e., won't even an attempt at raising taxes guarantee a big GOP win in the next election?