Successful Future Humanities Programs Will Be Those That Provide High Literacy & Deep Numeracy

To get through the crisis, humanities programs should focus on equipping students to understand and act in the largely-symbolic networked world that surrounds them. My view: the crisis in academic...

To get through the crisis, humanities programs should focus on equipping students to understand and act in the largely-symbolic networked world that surrounds them. My view: the crisis in academic humanities is not "political"; it is educational…

This last post-Thanksgiving weekend I found, in my email inbox, a wise thought from Matt Yglesias:

Matthew Yglesias: Thankful mailbag: ‘While entertainment is fine, it’s also good intellectual discipline to try not to develop false beliefs. So you ought to be at least a little suspicious of writers who you enjoy because everything they tell you is psychologically pleasing. There’s a real skill to that. To “explaining” to people in your ideological niche why every passing event in the news demonstrates their basic correctness about everything. And that kind of content, well, it can make people really happy. But it’s likely to be misleading….

And, via synchrony, I make one of my increasingly rare expeditions to Twitter—it really does give me hives these days—to find Matt Yglesias saying something I did not enjoy, and did not think was wise:

Matthew Yglesias: ‘I think a big part of the "crisis" in the liberal arts <https://twitter.com/mattyglesias/status/1728405687162827209> comes down to the fact that the people who teach these classes no longer want to do what society wants them to do and expound on the greatness of our civilization…

At first I dismissed this as the Twitter effect—turning geniuses into normal people, normal people into morons, and angry people into Nazis or Stalinists or Stalinist-Nazis.

But, yes, he did expand:

Matthew Yglesias: Thankful mailbag: ‘There’s just a big divergence between what most people see as potentially valuable in the liberal arts and what most humanities faculty think is valuable and important…. Educated professionals… technical specialists (engineers, scientists, doctors)… [plus] lawyers, teachers, middle managers… a sort of collective social elite…. Over and above the specific skills members of this elite need to do their jobs, it’s good for them to be inculcated with… values… the history of proto-constitutionalism in England and the classical republics… religious freedom… not a sectarian point (the point is religious freedom!)… develop[ed] out of the specific circumstances of the Protestant Reformation….

Historical events… Greece to Rome to “the Dark Ages” and the Renaissance and Reformation and the founding of America… philosophical lineage from Plato and Aristotle to Hobbes and Locke and Mill and Rawls… literary and artistic cultures that were informed by these historical and intellectual trends and that also informed them. And you have traditionally had a belief that it is important for important people to be broadly educated in these themes….

That kind of traditional broad liberal education would of course involve some exposure to radical critics of Anglo-American liberal capitalism (it’s good to be well-informed) and perhaps even a smattering of instructors who endorse the radical critiques (it’s good to sit in rooms and listen to smart people with ideas you don’t agree with), [but] the current trends on campus are toward an atmosphere where the radical criticism predominates…. The critical theories themselves would tell you, there’s no way Anglo-American liberal capitalist society is going to sustain generous financial support for institutions whose self-ascribed mission is to undermine faith in the main underpinnings of society…

I find this last paragraph annoying. And, not just annoying, but it sets off alarm bells. This “current trends on campus are toward an atmosphere where the radical criticism predominates” is something I would expect to read as an irritable gesture from an underbriefed old-person-yelling-at-clouds writer like David Brooks or Bari Weiss, not from Matt Yglesias. So I want to call “bullshit”. But should I?

OK. Let’s collect a little data here (and let me telegraph my conclusion by saying that, yes, I should call “bullshit”—mostly):

I will not say that what I see from my vantage point here in the Elmwood neighborhood of Berkeley is representative. But I will say that here at the University of California at Berkeley, I ought to be in the Belly of the WOKE BEAST if anyone is. What do I see if I look around?

Here, from a file near the top of my “Downloads” folder, is a page from a Berkeley history-department current-semester syllabus:

What do I think? This is squarely in my wheelhouse, as perhaps you noticed from one of the works assigned. “Radical criticism” does not predominate. Indeed, radical criticism is only presented here by Harvey—which, I admit, I would never assign: I do not find him wise, or widely read outside of his narrow personal bubble, and I find it very difficult to read him with a hermaneutics of charity: I find myself thinking “this cannot be written in good faith” every other page. But “self-ascribed mission is to undermine faith in the main underpinnings of society”?

Definitely not.

And here, from the most recent hit searching for “syllabus” in my “Downloads” folder, are three pages from a Legal Studies syllabus:

French revolutionaries, Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, Karl Marx, and Henry Maine. Karl Marx certainly intends a radical critique of bourgeois law—that it is not a way of constructing a win-win web of human social interaction and cooperation, but rather a more subtle and more powerful tool of the force-and-fraud gang that dominates: you make, we take, and then we eat. Here and now, nearly two centuries after the Communist Manifesto, I would certainly not give the Marxian critique such a large amount of mindshare. But, again, calling this an example of any Berkeley academic department’s “self-ascribed mission is to undermine faith in the main underpinnings of society” seems way over the top.

Last, here are nine syllabus pages grabbed off of Tau Beta Pi’s Exam & Syllabus Database <https://tbp.berkeley.edu/courses/>—a “Race & Cinema” course, two pages from a survey of American history from WWII to 9/11, an art-history survey, a modern American-history survey, a “new media” course, “Wealth & Poverty”, “Roots of Western Civilization”, & an 1860-1940 American-history survey:

In the first row:

In the top left, “Race & Cinema” seems to me a fine thing to teach, and these are all very good movies to watch, and there is great value in thinking about text and subtext.

In the top center, I begin to feel considerable sympathy for Matt: this course—U.S. history from WWII to 9/11—is, here, covering World War II, and the fact that the big WWII story is defeating Nazis (and imperial Japanese colonialism—their attempted conquest and subjection of Korea, China, Indochina, Indonesia, the Philippines, and New Guinea) via an amazing and enthusiastic mobilization of productive resources is all-but completely absent. Yes, the internment of Japanese-Americans was a hideous and cruel error. Yes, Truman probably was not happy afterwards with his decision to barbecue more Japanese civilians with atomic weapons… but, still, if this is Hamlet, shouldn’t the Prince of Denmark appear as the protagonist of even one scene?

And in the top right, when I gave this course another chance—well “World Trade Organization, Apartheid, Nelson Mandela, Genocide” are not adequate keywords for “Globalization”; not unless your narrative through-line is how global civil society and outside economic pressure undermined the confidence and authority of South Africa’s Afrikaaner ruling race, and I do not think that is the case here.

In the second row:

In the center-left, it looks to me like students get to appreciate a very large number of very great paintings.

In the center-center, we get what I think of as standard readings on culture and modern American capitalism, and I think these are the right readings—save for Vance Packard, which I find overwrought and somewhat paranoid.

In the center-right, we get a “New Media” course which I think largely misses the mark because it is too grounded in the writings of the Frankfurt School, for which “New Media” meant “radio”

In the third row:

The bottom-left is a page of Bob Reich’s assigned readings on the modern social-insurance state: they are the right readings.

The bottom-center are the “Roots of Western Civilization” from Gilgamesh to the Aeneid. This gets my hackles up in the other direction. From Uruk to Rome we have great civilizational accomplishments accompanied by extraordinary cruelty, violence, and domination. They would certainly not recognize us as their legitimate descendants. We appropriate from them things we like—but this is our choice, for we are in no sense “rooted” in them.

And the bottom-right is a page of what have long been very standard readings about America from the Gilded Age to the New Deal.

I repeat: I AM A PROFESSOR AT U.C. BERKELEY. I AM IN THE BELLY OF THE WOKE BEAST. And yet when I look at what my colleagues here in the humanities are teaching, what I really do not see is a bunch of humanities departments that are “institutions whose self-ascribed mission is to undermine faith in the main underpinnings of society”.

What do I see to criticize? I see:

A somewhat excessive mindshare given to Marx and his epigones—Frankfurt School, and, cough, Harvey—in Legal Studies and Media Studies…

A little too much drinking of the old-fashioned “WESTERN CIV” koolaid in Classics…

A History course that I would put under the aegis of Matt’s “instructors who endorse the radical critiques…”—although I would add that what disturbs me is not the instructor’s position, but rather the narrowness of the reading list. But that is perhaps (probablyd?) offset in lecture. I do not know, and rather than presume I should find out.

But taken all in all, I see lots of smart people—many of whom I have profound disagreements with—teaching a lot of different things, I do not see any collective “self-ascribed mission… to undermine faith in the main underpinnings of society” or any group unwillingness “to do what society wants them to do and expound on the greatness of our civilization…”—the thing to which Matt attributes “a big part of the ‘crisis’ in the liberal arts…”

So what is going on here?:

Are Berkeley humanities profoundly “unwoke” relative to your standard university? Doubtful, but I really don’t know.

Has Matt been spending far too much time reading Twitter and debating right-wing professional within-the-beltway grievance-mongers, and has that warped his perception of reality? Probably, but I really don’t know.

Are <http://vox.com> in particular and left-oriented organizations in general hiring from a thin slice of Ivy League humanities graduates who have self-defined as uninterested in business, engineering, science, or technology, but rather in changing the world solely through their keyboards? And have they been mis-taught in their upper-level courses? And has that warped his perception of reality? Perhaps, but I really don’t know.

So far, all I have is scanning some syllabuses—I haven’t gone to lots of recent humanities lectures or attended lots of discussion sections.

Swarthmore’s Tim Burke is much closer to the center of things than I am, and provides us with what I think is a more fruitful way into the problem:

Burke writes about a “liberal” education as one that evolved since the year 1000 in Europe as one aimed at preparing students for uncertainty and contingency on the one hand and for their professions on the other. In their general education students needed to learn a little about a lot—so that they could orient themselves—and also a lot about a little—because there is great value in learning in-depth about other modes of thought than that used in your particular profession. And then they needed to become expert in their profession as well. People needed an open-ended education to prepare them to face complex and novel problems, and also to learn practical arts for specific kinds of intellectual labor.

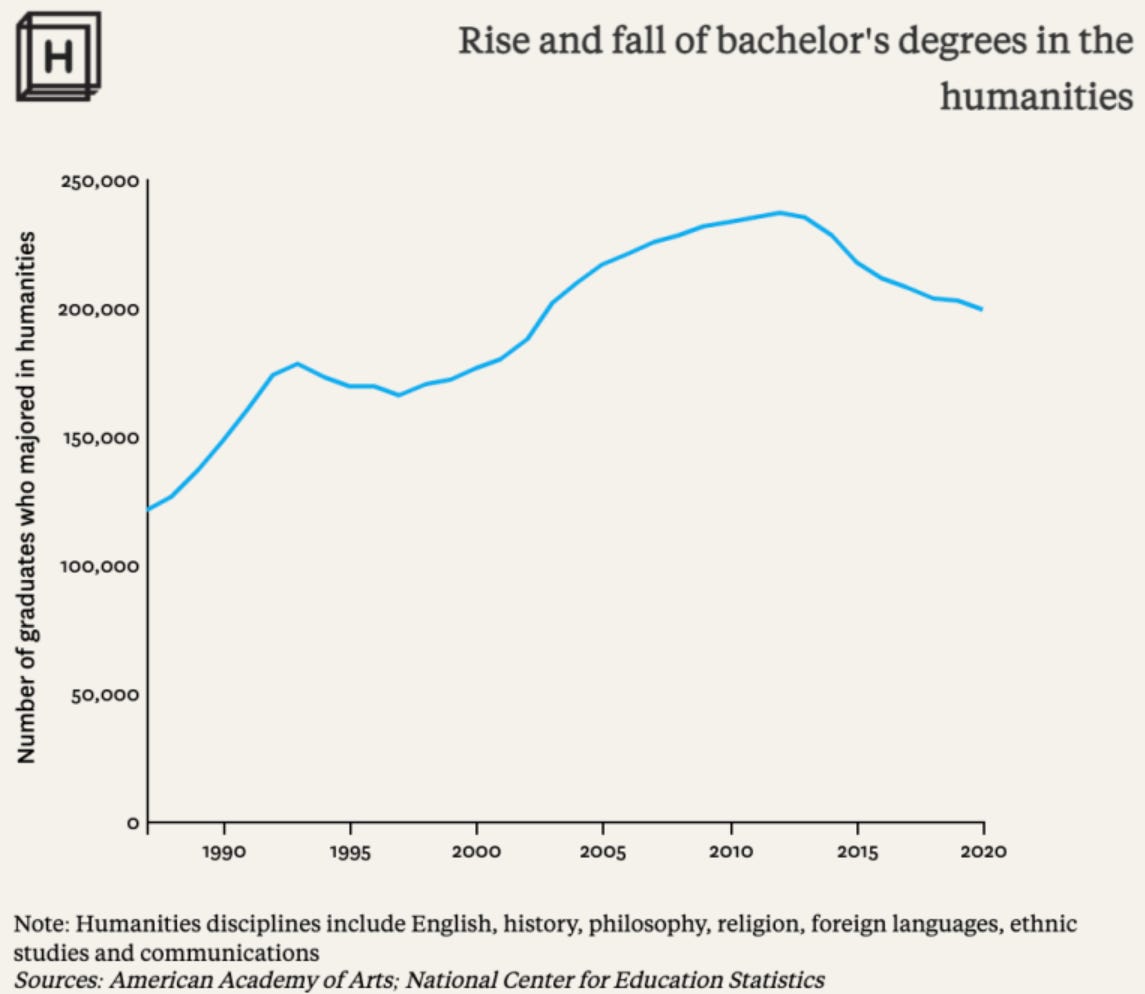

And it is in this context that he worries about the liberal-arts crisis, which is, indeed, very real:

In Burke’s view, this is because the humanities have promised what they cannot deliver. They promised:

The medieval European understanding… based partially on a reinterpretation of classical ideas, asserted that… open-ended education based on the trivium and quadrivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy)… [was good for those who] would face complex and unexpected problems…[and needed more than] introduction to “practical arts” relevant to specific repeated labor with a known value…

But what are they delivering today?:

Our conceptual assumptions about how to teach to uncertainty are almost inchoate and the empirical evidence of whether we do so successfully is debatable. If we are in any sense successful, I think we have no idea what it is that we are doing that accounts for that success—and arguably it has nothing to do with anything taught in higher education but is instead about social capital and available economic resources. This is where “preparation for uncertainty” lives alongside other reassuring concepts like “resilience”, “emotional intelligence”, or “grit”. They may not be measuring either attributes that people have that can be developed in others or concrete skills that are teachable, but instead just “do you have access to money and to social networks?”….

What exactly are those structures and practices?… Many of us would answer “critical thinking”…. Graduates learn to view the world around them skeptically and provisionally, and that this in turn prepares them to adapt rapidly to changing economic and social conditions (and to help lead or direct processes of change for others)…. We could decompose “critical thinking” to far more specific epistemological and methodological commitments in various academic disciplines: the scientific method, thought experiments, close reading, etc. and get a better account of how to teach skepticism, provisional truth-making, and so on. Possibly….

What I fear we mean sometimes when we say that a liberal education is preparation for uncertainty is… an attempt to naturalize and justify the labor markets of the early 21st Century. The uncertainty and instability of those markets is a product of the credulous and wholly ideological celebration of “creative destruction” and “disruptive innovation” by the oligarchs of our present American moment and their courtiers.

There is nothing inevitable, desirable or natural about the proposition that industries, workplaces, jobs, and communities should perpetually expect to be broken, eradicated or discarded at any moment by private equity firms, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, or crony capitalists. The proposition that training for uncertainty means accepting the need to change everything about your skills, values, desires, aspirations and material situation at a moment’s notice not because you wish to change but because a few people with extraordinary wealth and power have almost incidentally destroyed everything about your status quo is not the cunning of uncertainty but the craft of exploitation and domination….

Maybe a liberal education is about embracing uncertainty where it is generative, necessary and useful. And maybe we’re middling-skilled in teaching that embrace. But we shouldn’t accept that the job of a liberal education is making graduates live complacently into what has been done to them and their possible futures…

In Burke’s view, the humanities (a) do not, except accidently and haphazardly, deliver; and (b) when they do deliver much of what they deliver is a willingness to be passively slotted into a chaotic exploitative economic system.

You will not be surprised that I have a somewhat different take on the fact that the combination of technological change, Schumpeterian creative-destruction, and the von Hayekian market pushes toward a world in which “industries, workplaces, jobs, and communities… [are] perpetually…broken, eradicated or discarded at any moment…” In my view, the right response is not root-and-brance resistance to change and preservation of an often much more oppressive old structure just because it was what was, but rather Polanyian management. But I have written about that at length:

However, I would put the problem somewhat differently. I would put it that the humanities could deliver something useful, and we might as well call that “critical thinking”. But what we need is not a pure uncovering of deep structures and peeling-back of ideological legitimations, but rather a much more preprofessional version of looking critically at the world around yourself, both for understanding and to give you tools with which to take action.

A “liberal” education is for someone who is free—that is, both not entangled in the webs of control that make everyone else subservient and in their place in the feudal and later the status system, but also without control over resources that a place in the feudal and later the status system would give them. They thus have to live by their wits. And so they must learn to be useful and persuasive.

Hence the Trivium—logic, grammar, and rhetoric: how to think, how to write, and how to speak. Hence the Quadrivium—arithmetic, geometry, harmony, and astrology: how to calculate quantities, understand spatial and geographic relationships, and… harmony and astrology seem (to me at least) less clear as required foundational studies. And then you go on to your professional faculty—theology, law, medicine, in order to make yourself immediately useful to someone who might hire you, either a bishop, a governor, or a hospital.

The “liberal arts” were never not professional. They were the intellectual-capital skills people needed to acquire to make their way in medieval and post-medieval society by their wits.

Viewing that as the project of liberal-arts education, the 1800s in Britain and America seem to be a deviation in that there seems to be a growing disconnect between what the university teaches and what people need as intellectual capital for post-college life. It seems to me to have become more a finishing school for landlords, or for those who have a family business they can go into, than a “these are the high literacy and numeracy skills you need to find a place in a society that has few places for those unbound by network ascriptions”. Thus what I see now is, in all likelihood, a return to the earlier more-preprofessional pattern, with what higher education having to teach being:

Literacy—written presentation-of-self-and-argument in English prose

Rhetoric—oral presentation-of-self-and-argument in English in person

Preprofessional, chiefly:

Biochem

Computer software engineering

Business and finance

And our students are, increasingly, trying to vote-with-their-feet for that.

Now there does remain that value of learning a little about a lot, and a lot about the little using a mode of thought not aligned with your profession. But a university with an increasing focus as an educational institution on literacy, rhetoric, plus biochem, computer science, and business and finance will look somewhat different than post-WWII American colleges and universities have looked. Thus from my perspective, the crisis in the humanities is that they have not figured out how to focus on what will be their teaching missions:

how to persuade in person

how to persuade in prose

how to quickly pick up on and relate to somebody using a different mode of thought

knowing a little about a lot—and knowing how to quickly, reliably, and comprehensibly learn more.

As Chad Orzel says of this last:

Yes, says the guy with a faculty position at a liberal arts college with an engineering program, that’s exactly the point. “Liberal arts education” doesn’t mean “majoring in something involving literary analysis” it means “taking classes in many different types of subjects on the way to a degree in absolutely anything.” The idea of liberal arts education is absolutely compatible with majoring in engineering or even— quelle horreur!— business, provided that students don’t only study the one narrow area in which they’ll get their degree. It’s an attitude toward education, not a list of majors or even colleges. In fact, getting those positive attributes into engineering and business (and science, and math, and economics, and…) degree programs is exactly what we should want…. What we need isn’t more people in decision-making roles who majored in “the humanities,” what we need is people with a liberal arts education…

Students, it seems likely to me, aren’t voting-with-their-feet for fewer humanities because they have been taken over by “theory”-heavy left-wingers on a self-appointed mission to undermine confidence in society. Chad Orzel was in college. And he despised his medieval history class because of its theory-heaviness:

Chad Orzel: What I Learned From the Liberal Arts: ‘A weird mix of chronological survey and critical grab-bag. So one week we were reading Chaucer and talking about Marxist interpretations thereof, and a week later we were reading romances and talking about feminist interpretations. But there wasn’t really any clear sense about why you would prefer one or the other– the critical sources didn’t even really acknowledge each other. The Marxists wrote as if analyzing everything in terms of class and power was the only sensible approach, while the feminists wrote as if only a blithering idiot could fail to see that everything was an allegorical reference to genitalia. But it wasn’t obvious that you couldn’t swap them around and get equally plausible results, other than the fact that you tended to get blisteringly snide comments if you tried that and came up short of some poorly defined standard. This strongly contributed to the impression that the entire thing was a pointless bullshit game…. There is, of course, a cynical sense in which the bullshit game nature of the classes was the most useful thing I got out of it. That is, having gone through those classes helped me refine my ability to write in very different modes, so I can plausibly imitate the style of various sorts of documents without actually buying into any of it. But we’re trying to get beyond cynicism, here…

As someone who thinks that The Romance of the Rose is as much about sex as about a princess in a tower, I do think that there was value in that medieval literature class that Chad Orzel did not connect with. But I do think that was the professor’s fault—theory-heaviness can be really deadly.

But very little of the crisis in the humanities, at least from this outsider’s perspective, comes down to that the “people who teach these classes no longer want to do what society wants them to do and expound on the greatness of our civilization…”

As is your wont, you are too kind to Matt here. He didn't make any effort to substantiate his claim, he just stated it as fact. Your rebuttal may not be sufficient strictu sensu -- though I think it works quite well a fortiori -- but it's not your burden of proof.

I'd like to add a purpose for the humanities beyond what you mention: that they should provide the public good of making proper citizens. I don't know how much modern humanities courses teach the principles of liberal democracy, but it's the Right's hatred of that which in reality drives the criticism to which Matt refers. The humanities should not be seen as an apologia for our current society, but as a reminder of how we got here -- the successes along the way *and also the failures that we should work to fix*.

While US university education requires more liberal education than UK universities at a cost of an extra year to graduate, are we not in an ever deepening situation that C P Snow once expressed concern about in his 1959 lecture "The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution"? [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Two_Cultures ]. 60+ years later, science has made huge strides forward, yet we pick our leaders from the humanities, whose ignorance of basic science is not just appalling, but in the US and UK, often worn as a badge of honor. IDK what we should be teaching humanities students - it isn't my field - but over my lifetime it has become ever clearer that we pick our leaders from a rather narrow expertise, and worse, that expertise in science and engineering is often ignored despite institutions that have been set up to provide it. I don't think we need to have a strictly technocrtatic governnance, but we really need better informed governance to successfully navigate our increasingly technological and complex world.