The Expectations Debate Again: Why I Think That It Is Likely We Would Still Have an Inflation Problem If Jay Powell Had Not Acted in 2022

It is not just that keeping interest rates low would have in all likelihood led to an overheated economy with wage-push inflation; it is also that inflation expectations looked like they might have...

It is not just that keeping interest rates low would have in all likelihood led to an overheated economy with wage-push inflation; it is also that inflation expectations looked like they might have been beginning to drag if not slip their anchor...

Is this from the very sharp Mike Konczal correct?

Mike Konczal: What to Expect of the Expectations Debate: You are going to hear more about “expectations” in the year ahead, so it’s worth doing some stage setting for how this debate will go. I’ll certainly be revising my views on this; but this is my first pass to end 2023.

I want to distinguish between three similar, but different, arguments:

The Fed drove the disinflation in 2023 through inflation expectations.

Steady long-term expectations of inflation provided an anchor that helped allow the reopening shock to remain transitory.

The Fed was required to take interest rates into restrictive territory in order to keep (2), in order for long-term expectations to remain anchored. Without restrictive rates, the reopening shock would have become persistent instead.

[a] I think the first is wrong. [b] In current DSGE models that involve forward-looking expectations, you can (controversially) have disinflation uncorrelated with economic activity or unemployment through changes in what people expect inflation to be in the long-term. [c] But that requires actual movement in long-term expectations, one-for-one movements generally. We have seen that kind of movement before, e.g. in the United States during the 1980s. We don’t have any equivalent movement now; there’s simply no variance in long-term measures of inflation in the past year that could justify the disinflation we’ve seen. [d] Without that, the straight-forward version of the first argument doesn’t hold…

The distinction between (1), (2), and (3) is very useful. But let me go through that last paragraph sentence-by-sentence:

[a] I would agree with Mike that (1) is wrong if you amend it to read: The Fed drove the disinflation in 2023 through changing inflation expectations. Without that amendment, (3) becomes a subclass of (1), and I think that (3) is true.

[b] I REALLY DO NOT CARE WHAT HAPPENS IN CURRENT DSGE MODELS. THEY ARE A COGNITIVE DENIAL-OF-SERVICE ATTACK AGAINST THOUGHT IF YOU TAKE THEM AS ANYTHING MORE THAN A THEORETICAL BOUNDARY MARKER OF SOME SORT. THINGS TRUE IN THEM CAN BE FALSE IN THE ECONOMY. THINGS FALSE IN THEM CAN BE TRUE IN THE ECONOMY.

[c] Wait a minute! Let’s roll the videotape.

Here we have the ten-year inflation breakeven—the rate that CPI inflation would have to average over the next decade in order to equalize the returns between a nominal and an inflation-projected ten-year Treasury Bond held to maturity:

The red line corresponds to the Federal Reserve’s current inflation target: a 2.0% per year flexible average for the PCE inflation index. As you can see, up until the late spring of 2021 the bond market thought that we were likely to still be in a régime of secular stagnation—one in which the Federal Reserve was failing to hit its inflation target on the low side. Then from the late spring of 2021 through early 2022 the bond market’s expectations are for the Federal Reserve to hit its inflation target, on average, over the next ten years.

Now look at the red circle. Between February 22 and March 9, 2022, the ten-year inflation breakeven breaks out to the upside, reaching on March 11 a level of 2.94% per year as the average future CPI inflation rate. On March 15 the Federal Reserve for the first time raised interest rates, by 25 basis points. The ten-year inflation breakeven did not move. It kissed 3.02% per year on April 21.

Bond market inflation expectations had shifted.

Suppose, on April 21, 2022, (a) you had warrant to think that bond-market inflation expectations were both rational and representative of broader economy-wide expectations, and (b) suppose you were willing to hazard a guess that people in general thought that there was a 2/3 chance that the Federal Reserve would hit its target on average.

Then you would have said that:

There was a 2/3 chance that things would normalize, and that Fed monetary policy would be such as to hit the inflation target over the next decade—maybe higher by some, maybe lower by some, but on average.

There was a 1/3 chance that CPI inflation over the next decade would average a number higher than 2.5% per year on a CPI basis—and a reasonable guess would be that, along that branch of the distribution, we would see a decade averaging something like 4% per year inflation, maybe higher and maybe lower.

Now you might say that implicit bond-market bond-trader expectations among those active in the Treasury market have nothing to do with overall inflation expectations by real people whose decisions count for wages and prices. But I think that is an unwise thing to say. You might say that implicit bond-market bond-trader expectations among those active in the Treasury market are much more sensitive to news and misinformation and panic than overall inflation expectations by real people whose decisions count for wages and prices. And I would say you have a point.

But I would say that if you believe bond-trader expectations give us some information about real-people expectations, and if you believe stagflation can be driven by expectational shifts caused by a loss of credibility in the central bank, then you would have to say that, at least as of April 20, 2022, a decade featuring stagflation was definitely on the menu of possibilities.

Then, over the next month, from April 20 to May 20, implicit bond-market bond-trader inflation expectations to a level consistent with the Fed hitting its target over the next ten years.

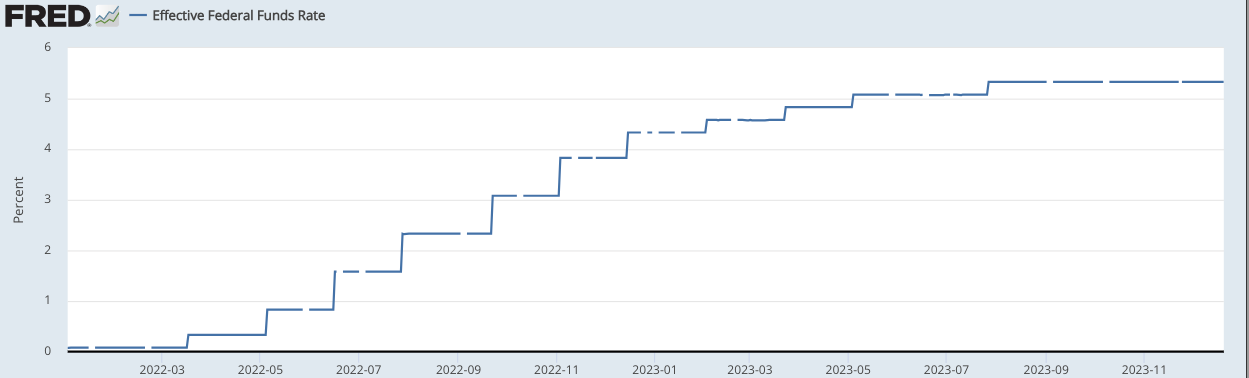

On May 4, 2022, the Federal Reserve raised its Fed Funds target rate by 50 basis points, from 0.33% per year to 0.83% per year, and reaffirmed its commitment to its price level target in spite of the supply shock caused by Putin’s invasion of Ukraine:

On June 17, they would further raise the target by 75 basis points to 1.58% per year, and in the meantime reinforced their message that they would do what it takes to hit their inflation target.

Thus I think that, more likely than not, there was movement in inflation expectations—but it was definitely not that expectations rose, inflation rose point-for-point, the Fed took action, expectations fell, and inflation fell point for point.

But I don’t think any of those arguing that “The Fed drove the disinflation in 2023 through [the effects of its monetary policy moves on] inflation expectations” would argue that. They argue that inflation expectations would likely have become unhinged in the absence of the action the Fed started taking in spring 2022.

[d] Thus, while I agree with Mike that a straightforward version of (1) does not hold, care needs to be taken to specify the counterfactual, and thus the meaning of “drive”.

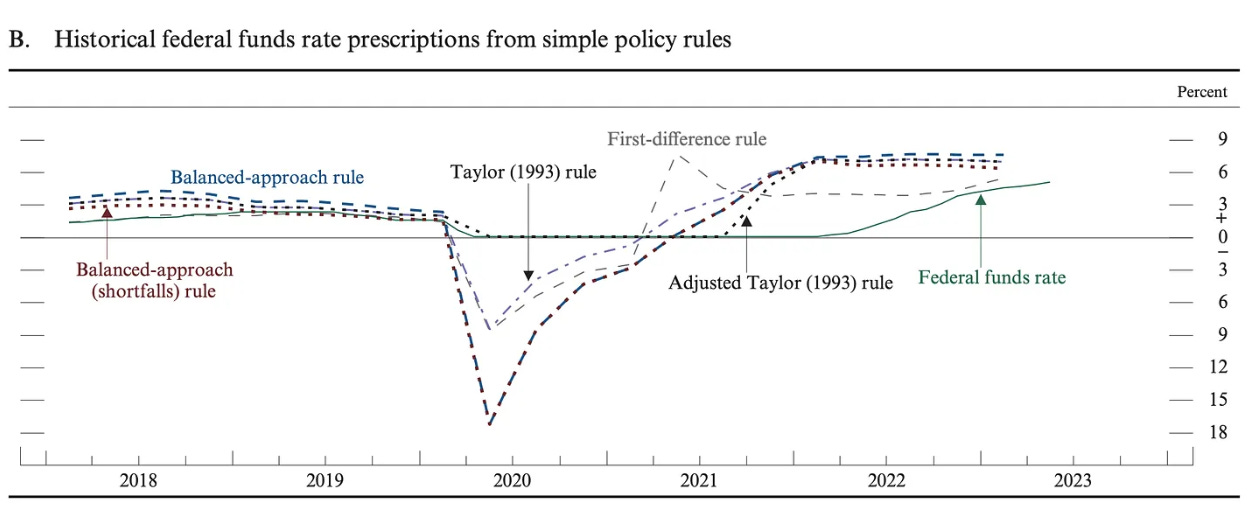

On the other hand, I would 100% agree with Mike’s first bottom line that in moving late and then moving relatively fast:

the Fed wasn’t as restrictive as the level implied by the [Taylor-rule] inflation régime it is generally understood to be following…. ‘Powell got really tough’ seems like a stretch. ‘Powell took out insurance against a bad case of a transitory shock becoming permanent’ seems more like the read…

And I agree with Konczal’s call for people to remember and praise Reifschneider & Wilcox (2022), and with his second bottom line: that it is by far the best to:

understand… the shock we just went through as the type of shock that is temporary if we don’t screw it up… [not] a demand shock above a more general idea of potential output. These arguments are subsumed under the question “how should policy respond to a supply shock?” which is a good question to be thinking about in the years ahead. But, whatever stock you take in expectations here, they don’t really shake the reopening story at its core…

References:

Robert Armstrong & Ethan Wu: 2023. “Larry Summers: we haven’t nailed the landing yet”. Financial Times December 14 <https://www.ft.com/content/59fff67e-b136-4435-89e1-2400b90f4b83>.

DeLong, J. Bradford: 2023. "Morning Notes on December 19, 2023 on the Inflation Debate" Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality.

Konczal, Mike: 2023. "What to Expect of the Expectations Channel."

Krugman, Paul: 2023. “Beware Economists Who Won’t Admit They Were Wrong”. New York Times December 18. <https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/18/opinion/inflation-economists.html>.

Reifschneider, David, & David Wilcox: 2022. "The Case for a Cautiously Optimistic Outlook for US Inflation." Policy Brief 22-3. Peterson Institute for International Economics, March. <https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/case-cautiously-optimistic-outlook-us-inflation>.

Weissmann, Jordan: 2022. "Why Larry Summers Thinks We Need Massive Unemployment to Beat Inflation." Slate July 7. <https://slate.com/business/2022/07/larry-summers-massive-unemployment-fed-inflation.html>.

Suppose we forget about timing for a moment. An increase of 0.6 per cent in the expected ten year inflation rate implies a price level 6 per cent higher than with target inflation. That's pretty much what happened in the post-lockdown period. If people expected the inflation to be transitory, then expected 10 year inflation would fall back to the pre-Covid level once that was past.

I don't think this story is consistent with full forward-looking rationality, but it seems to work.

Been thinking some more about the counterfactual expectations, ones that could've dislodged.

A way to gauge them could be to look at past episodes in the US and elsewhere of energy price shocks of similar magnitude and where the expectations DID get dislodged. That may roughly give us a sense of how much the Fed contributed by reining in the expectations to the level we actually observe.