Þe Killer App of Economics & History Is Counting Things (& All Math Is Just Counting Things)

& BRIEFLY NOTED: For 2022-01-25 Tu

CONDITION: Embarrassment:

This is an embarrassingly overpowered machine for what I am asking it to do:

First: I Have a Bad Feeling About This:

My 75 person class this semester is divided roughly equally into two parts, group #1 of which has seen and (hopefully) at least somewhat remembers macro economic growth theory before (and also has had some experience with computer programming), and group #2 of which has not. No I want the class to not learn but rather use a bunch of the conclusions of this growth theory. Thus I am taking the second week to either review, remind, or give the bottom line conclusions—depending on what they bring to the course.

So I want to be reassuring. But I don’t think this draft piece from my lecture notes is really going to reassure group #2:

In the Basic Solow Growth Model, the equilibrium economists look for is an equilibrium in which the economy’s capital-output ratio 𝜅κ is contant, and thus the capital stock per worker, the level of income and output per worker, and the efficiency of labor are all three growing at exactly the same proportional rate—a rate that remains constant over time. We will call this rate g, for growth.

Is this going by at bewildering speed? Blame it on the fact that our curriculum here in Economics is not well-designed. We want you to have the tools of economic theory to use here in this course. But we don't have time to build them from scratch. So we skate over the surface—providing a quick review to those of you who have taken Econ 100b before, and a skating-over-the-surface to those of you who have not.

Remember: we do not want you to understand the conclusions of these models and theories—we merely want you to know those conclusions, take them for now on faith, and use them.

As my teacher's teacher, the Nobel Prize-winning economic historian Robert Fogel once said, the killer app of history (and economics) is counting things.

Math is basically all about counting things. But we are very lucky, in that we stand on the shoulders of giants who have figured out how to and transmitted to us the knowledge of how to count things in incredibly powerful ways.

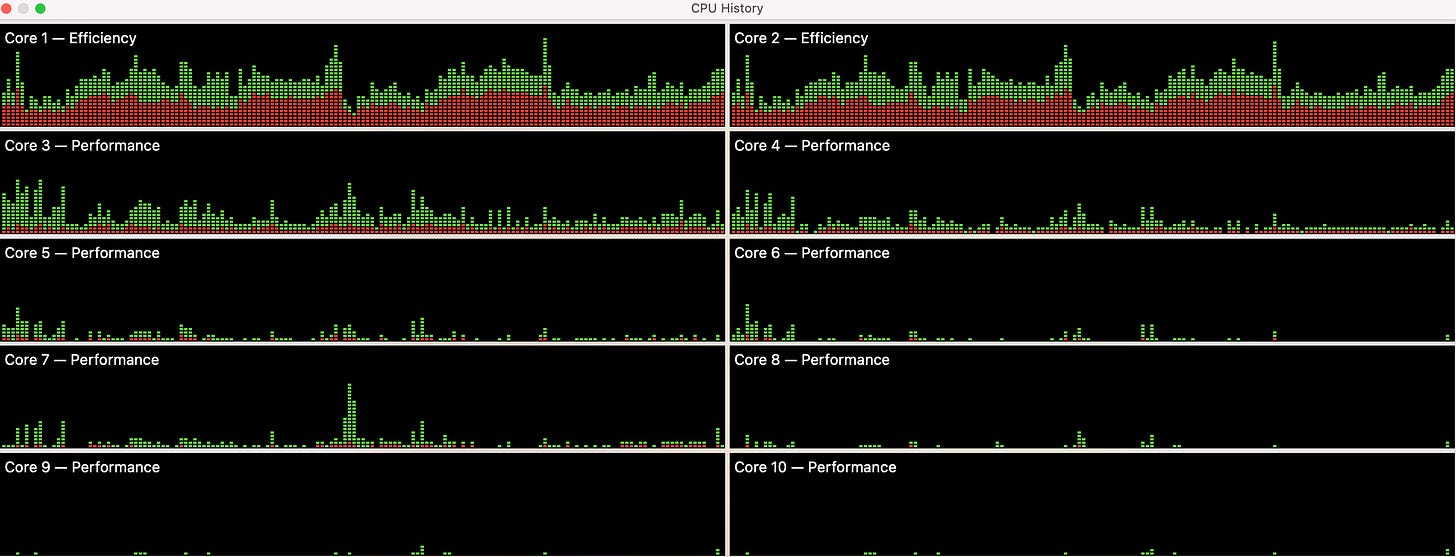

One such giant whose shoulders we stand on is Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (c. 780-850). The first part of his name is simply "Muhammad, son of Moses". The second part? It is the answer to the question: "OK. But which Muḥammad ibn Mūsā wandering around Baghdad in the early 800s during the reign of the Kalif al-Mamun are we talking about?” The answer was: "the one who came here from Khwārizm, and who works at the House of Wisdom established by the Kalif".

When Italians heard "al-Khwārizmī", they mangled it into algorithm. Every time you say algorithm, you are saying that you are undertaking the kind of step-by-step analysis that Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī taught us to do. Hew as the author of: Al-Kitāb al-Mukhtaṣar fī Hisāb al-Jabr wa’l-Muḳābala—The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing

It was his work on how to repeatedly and rapidly do large numbers of similar and related calculations that allowed us to turn simple counting into the mathematics of "what-if?" machines. We ask the question "what-if?" And we then answer it be doing a large number of calculations about what might be at once, seeing which of these calculations produce ansers that satisfy whatever the consistency and coherence conditions we have imposed are, and then summarizing the results of all of them in a very small space. It becomes complicated and very hard to remember and opaque very quickly. But, at the bottom, it is just counting.

Listen to physicist Richard Feynman, about how his QED theory of the interaction of light and matter—a theory that has been tested and is correct at unbelievably precise scales. As of 1985:

Experiments have Dirac's number at 1.00115965221 (with an uncertainty of about 4 in the last digit); the theory puts it at 1.00115965246 (with an uncertainty of about five times as much). To give you a feeling for the accuracy of these numbers, it comes out something like this: If you were to measure the distance from Los Angeles to New York to this accuracy, it would be exact to the thickness of a human hair...

No doubt experiments and calcuations since have sharpened both of those, and they are still in agreement.

Feynman, talking about this "Feynman Diagram" theory of his, said:

An analogy…. The Maya Indians were interested in… [when they would be able to see the War-Star] Venus…. To make calculations, the Maya had invented a system of bars and dots to represent numbers… and had rules by which to calculate and predict not only the risings and settings of Venus, but other celestial phenomena….

Only a few Maya priests could do such elaborate calculations….

Suppose we were to ask one of them how to do just one step in the process of predicting when Venus will next rise as a morning star—subtracting two numbers….. How would the priest explain?….

He could either teach us the… bars and dots and the rule… or he could tell us what he was really doing:

Suppose we want to subtract 236 from 584. First, count out 584 beans and put them in a pot. Then take out 236 beans and put them to one side. Finally, count the beans left in the pot. That number is the result….

You might say, ‘My Quetzalcoatl! What tedium… what a job!’

To which the priest would reply,

That’s why we have the rules…. The rules are tricky, but they are a much more efficient way of getting the answer…. We can predict the appearance of Venus by counting beans (which is slow, but easy to understand) or by using the tricky rules (which is much faster, but you must spend years in school to learn them)...

We stand on the shoulders of myriad upon myriad of armies of giants. All we have to do is to build in our brains a filing system so we can remember how to utilize the conclusions of all the work they have gifted us with, trusting that they were indeed giants and knew how to do their job.

One Audio:

Noah Smith: Interview: Ryan Petersen, Founder & CEO of Flexport: ‘The supply chain crunch, modern logistics, and that famous trip around the Port of Long Beach… <https://noahpinion .substack.com/p/interview-ryan-petersen-ceo-of-flexport>:

One Picture:

Cherie Priest:

sumer is icumen in

doge wat do ye do?

groweth seed and kanine bloom

but no potats for yoo

sing cuccu and

no tomats for yoo

LINK:

Very Briefly Noted:

Max Knoblauch: Mark Cuban Launches Online Pharmacy for Generic Drugs<https://www.morningbrew.com/daily/stories/mark-cuban-online-pharmacy-generic-drugs>

James Fallows (1991): “The Economics of the Colonial Cringe”: ‘Pseudonomics and the sneer on the face of the Economist… <https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/1991/10/-quot-the-economics-of-the-colonial-cringe-quot-about-the-economist-magazine-washington-post-1991/7415/>

Tim de Chant: Intel Says Ohio “Megafab” Will Begin Making Advanced Chips in 2025: ‘Intel will start with two fabs, but it has space for eight… <https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2022/01/intel-says-ohio-megafab-will-begin-making-advanced-chips-in-2025/>

Janan Ganesh: LA: The Great Walking City: ‘Weirdness and weather make it an underrated flâneur’s paradise… <https://www.ft.com/content/429fde28-9ecb-4ae4-aa3f-ba1aa95d445f>

Paragraphs:

Robert Leeson: Hayek: A Collaborative Biography: ‘In his history of the LSE, Ralf Dahrendorf (1995, plate 17, between 268 and 269) reproduced a photograph of academics dancing…. Hayek described Arthur Lewis, his LSE colleague and the winner of the 1979 Nobel Prize for Economic Sciences, as an “unusually able West Indian negro”; when asked what his “attitude to black people was…he said that he did not like ”dancing Negroes“. He had watched a Nobel laureate doing so which had made him see the ”the animal beneath the facade of apparent civilisation" (Cubitt 2006, 23)…

Jemima Kelly: Crypto Is Crashing But It’s All Going to Be OK, OK?: ‘The halvening, but probably ultimately even better for bitcoin…. Yes, you might have lost half your money if you got in a couple of months ago, but the OG HODLers who got in at $200 or whatever are starting to hurt a bit too and we need to keep in mind the equitable future of money free from the yoke of evil fiat fat cats that they all deserve. So BTFD, keep these OGs in their Lambos, and like, focus on some inspirational quotes or something…

LINK: <https://www.ft.com/content/0f3815da-861c-4274-ba5f-fa2d6c377baf>

Hinze Higendoorn: Perception in Real-Time: Predicting the Present, Reconstructing the Past: ’We feel that we perceive our environment in real-time, despite the constraints imposed by neural transmission delays. Due to these constraints, the intuitive view of perception in real-time is impossible to implement. I propose a new way of thinking about real-time perception, in which perceptual mechanisms represent a timeline, rather than a single timepoint. In this proposal, predictive mechanisms predict ahead to compensate for neural delays, and work in tandem with postdictive mechanisms that revise the timeline as additional sensory information becomes available. Building on recent theoretical, computational, psychophysical, and functional neuroimaging evidence, this conceptualisation of real-time perception for the first time provides an integrated explanation for how we can experience the present…

LINK: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364661321002886>

Liam Bright: ’My somewhat more detailed sense of the present balance of forces in something like The Typical Anglo-American University. The largest group, and not only numerically largest but over represented in positions of senior authority, are what I would call Generic Libs, left of centre but not especially so. Probably basically like Kier Starmer and Elizabeth Warren. They don’t understand and vaguely fear and resent woke students, who they think of as something like the mob in a Victor Hugo novel (the TV show The Chair captured this vibe well). One way in which I’m a culture war centrist is I think the university is simultaneously full of insufferable baby-wokes who discovered Politics in 2016 and have been awful ever since, and also resentful mediocrities who blame feminism for their inadequacy. We contain multitudes. The next next biggest group are the woke. Disproportionately represented among students and junior faculty you’d not naturally think it’s gonna be an especially powerful group. But they have four things going for them. 1. There’s often a power base for them in administration, as office for diversity (etc) often has more soft power than official position in the hierarchy suggests. 2. Some humanities disciplines ensure they will have representation at senior faculty level. 3. They have friends in the press so can credibly threaten bad publicity. 4. Most of all, they have asabiyya. They have the energy and solidarity of young people who believe in what they’re doing and why. This group feeling lets them achieve more than their often quite junior official positions would suggest. Third are resentful anti-wokes. Smaller in number than either previous group they usually feel a bit beleaguered. But they have three things going for them. 1. To get anything done you have to go via first group. The second group achieved that through fear. That works ok, but the anti-wokes thereby automatically get some institutional sympathy, as no one likes being pushed around and that’s how the generic libs feel when confronted by the woke kids. 2. They also have friends in the press, so have a similar credibly threat to the second group. 3. They have allies with formal political power, and Deans are very aware of the need to fend off right populist attack. There are of course other factions and interest groups, some of which can get a lot done, but Culture War wise these are the significant groupings…

LINK:

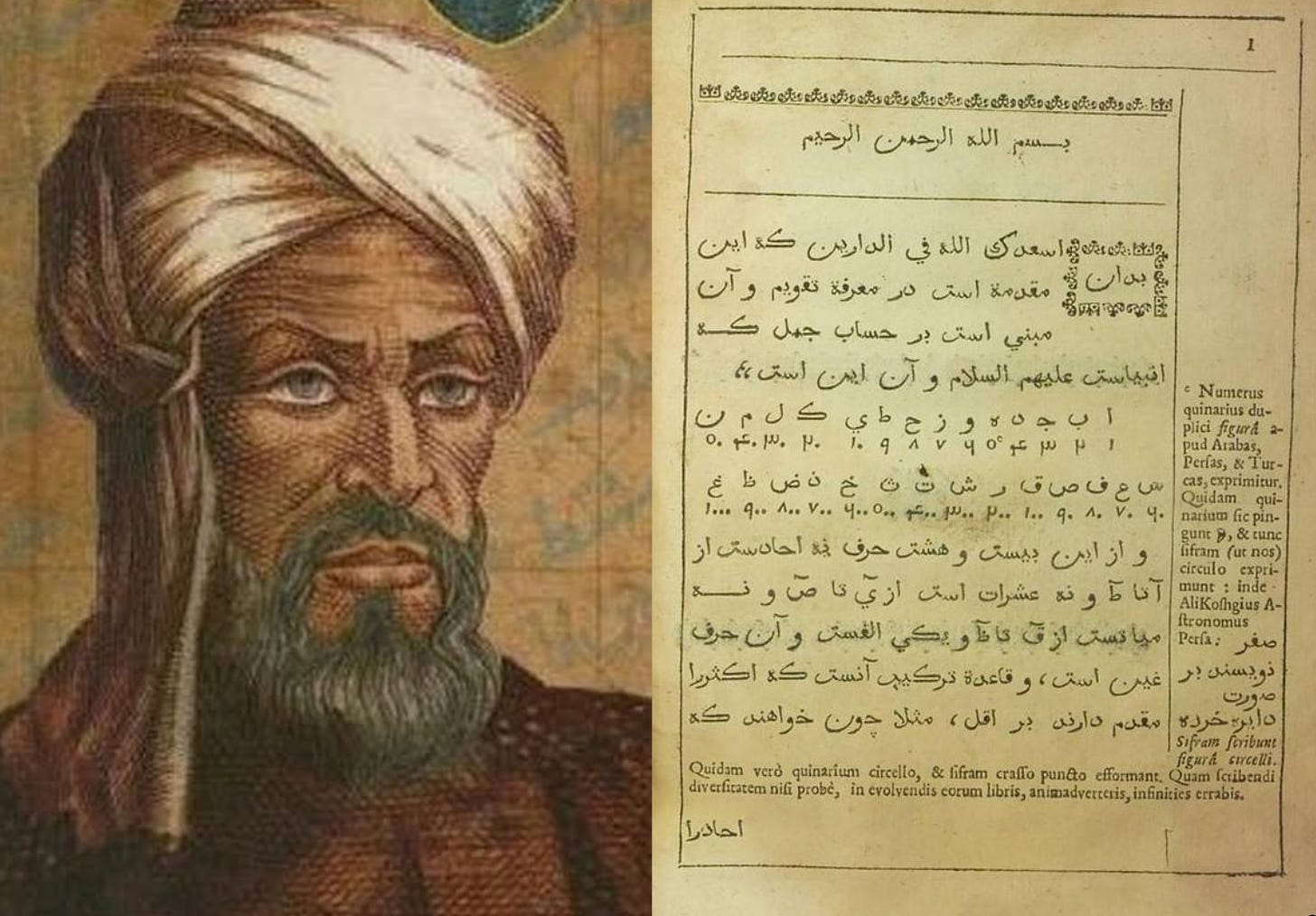

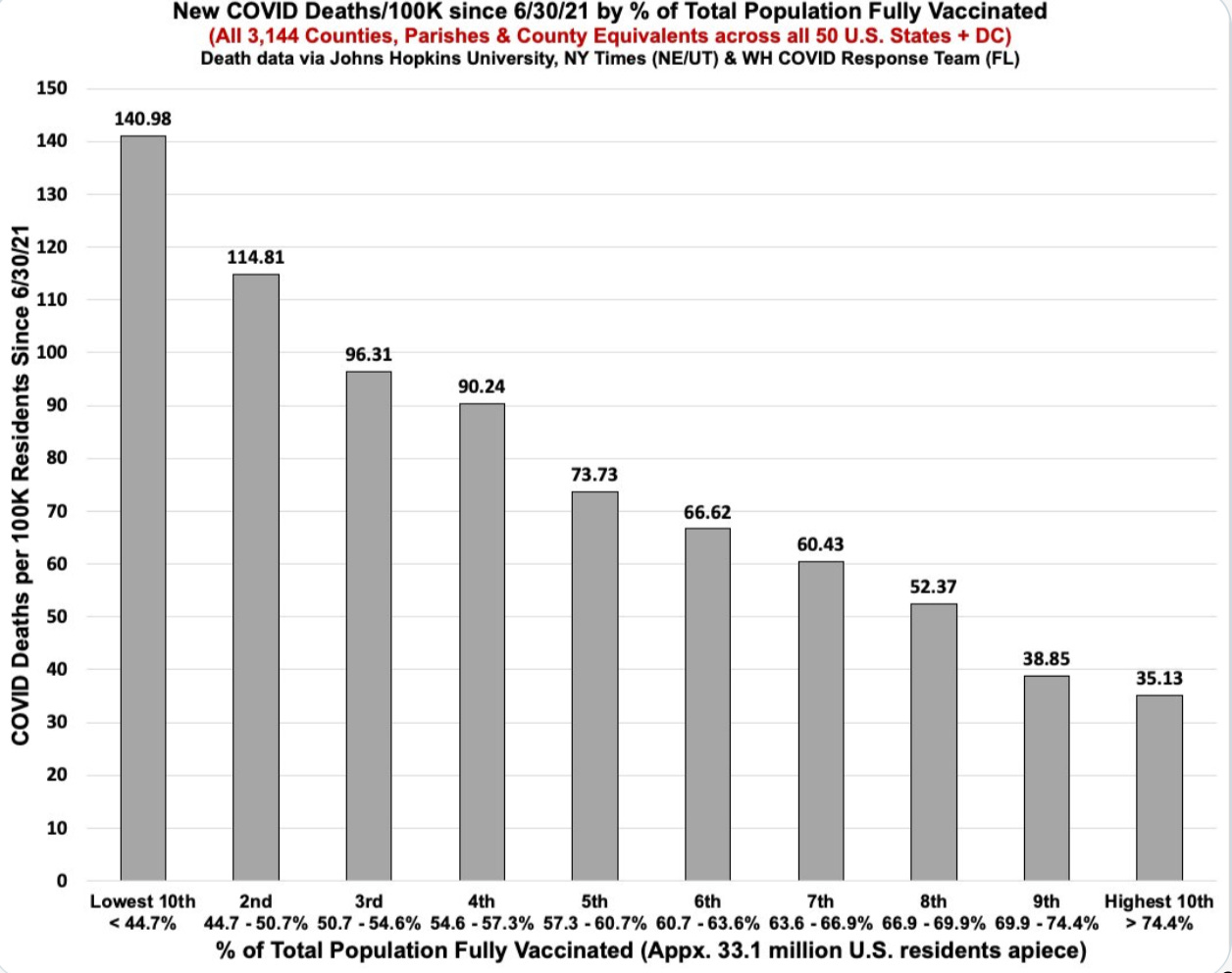

Charles Gaba: ’Unlike the Delta wave, which saw case and deaths hit the least-vaxxed counties with rates up to 4x or 5x as high as the most-vaxxed, Omicron has been the reverse in terms of case rates so far. As a result, here’s what things look like since June 30th for each. First, here’s what cumulative case rates from 6/30/21 - 1/21/22 look like broken out into 10 equal-population 2-dose vaccination deciles. As you can see, Omicron has completely cancelled out the prior trend… all 10 brackets have virtually identical case rates now. But here’s the kicker: Even with virtually identical infection rates in all 10 brackets, the death rate is still 4x higher in the least-vaccinated tenth of the country than the most-vaccinated tenth. I’ll have more on both trends and where they’re likely headed going forward soon. None of this actually surprises me, but I did a double take to see the case rate run virtually even across all 10 deciles at the same time–I figured there’d be more variance even as they shift. Two other important caveats to keep in mind: 1. These graphs include Delta and Omicron combined; they look very different separately (I’ll include Omicron only on a Monday blog post) 2. The vaxx data is based on 2-DOSE vaccinations; it does not include Booster data yet…

LINK:

If Americans reading The Economist "hear it in a British accent", then naturally the perceived 10 IQ point boost to anyone with a British accent comes into play. That perception faded 30+ years ago in cosmopolitan New York, took a little longer in SF and LA, but is still recognizable in the boonies of Central Valley California. I will say that the Economist of the 1970s and 1980s was a very different magazine to what it is now (I stopped subscribing to it in the 1990s). What I think Fallows mistakes is that like so many magazines that once were high quality but catered to a narrow audience, it succumbed to the desire for a wider audience, with the inevitable change in quality. This seems to be so infectious, and goes beyond magazines, (Scientific American being a case in point that became more like Popular Science under the leadership of Rennie), and I recall in the 1980s when an upmarket British crockery manufacturer was taken over by a conglomerate intent on widening its market and subsequently effectively ruined the brand. "Growth" seems to be the corporate version of the sickness of human greed.

Perception. It is interesting that the article uses the time delay in neural processing to ground the argument for prediction. Prior work has used the idea that prediction from past knowledge is an efficient, low cost method to track the present that minimizes cognitive effort. When the prediction does not match reality, there is increased cognitive effort to realign the prediction sequence. If the time delay is important, what would that mean for electronic perception in advanced robots where this delay is considerably reduced, allowing for less prediction to be needed to check against reality? Would such robots be closer to living in the "true present"? Would they be able to react much more quickly to prediction vs reality mismatches?