FOR PAYING SUBSCRIBERS: OUTTAKE: Risks of þe Cold War, & Ten on þe Western Side of the Iron Curtain Who Made a Big Difference

An Outtake from "Slouching Towards Utopia?: An Economic History of þe Long 20th Century 1870-2016", Chapter XV: Cold War

Every now and then the frozen stability of the USSR-USA Cold War teetered towards Armageddon.

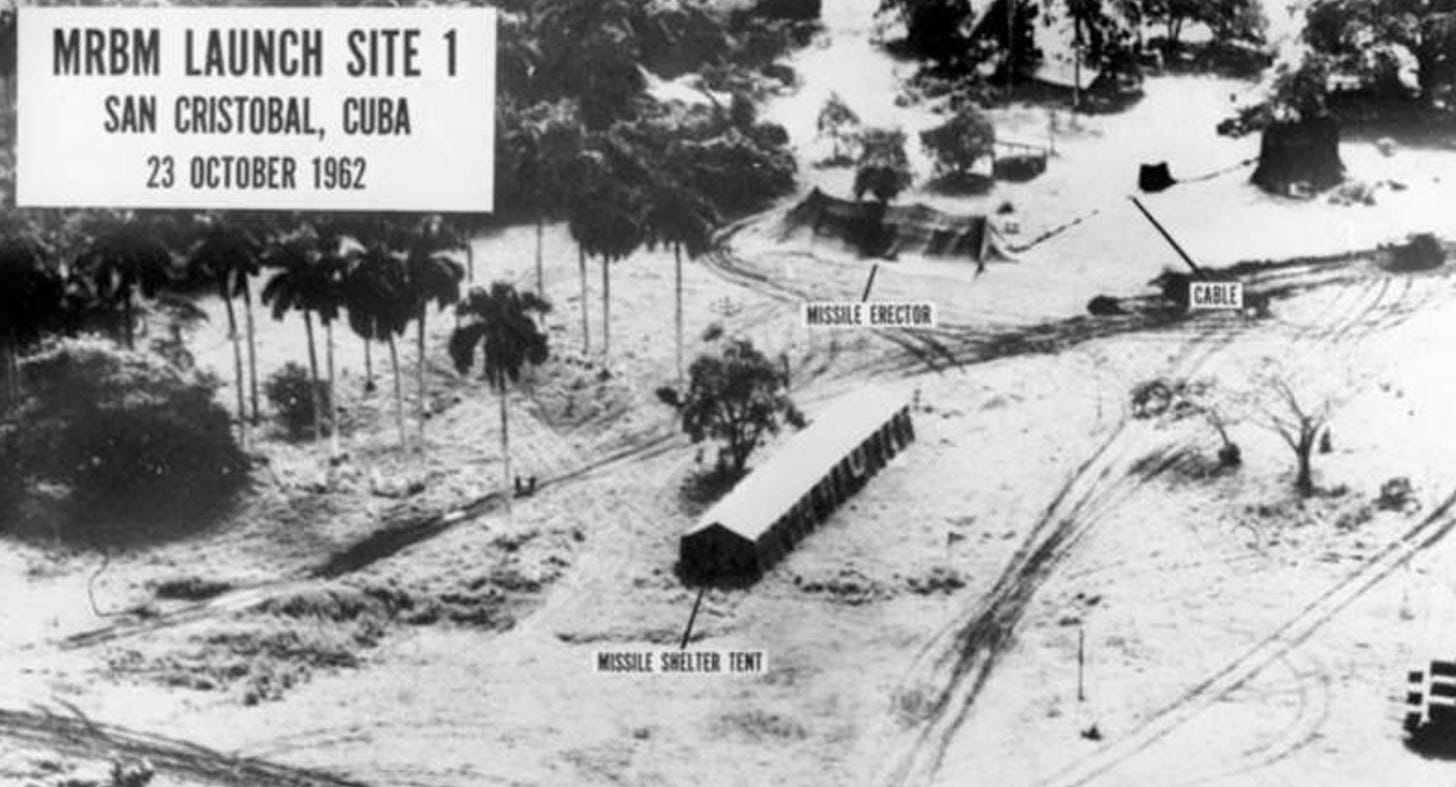

Humanity perched on the edge of thermonuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Nikita Khrushchev was somewhat surprised by the bellicose reaction of American President John F. Kennedy to Russia’s deployment in Cuba of missiles like those the U.S. had previously deployed in Turkey next to Russia’s border. In the end the U.S. promised not to overthrow Cuban communist dictator Fidel Castro by force, and Russia withdrew its missiles from Cuba.

More quietly, the U.S. withdrew its missiles from Turkey.

It has gone down in American political historical lore that, eyeball to eyeball, Russia blinked. Perhaps. But it should also be noted that Russia was the reasonable one willing to sacrifice “face”, for both sides agreed to keep the U.S. withdrawal a secret so as not to create a “Kennedy backed down” campaign issue that the Republicans could use against the Democrats in the 1962 and then 1964 elections.

A lot of grossly misleading histories were written by, and based on bad-faith reports from, Kennedy administration insiders over the next two decades before that secret was revealed.

There were other teeters.

In 1960 the moonrise was mistaken by NATO radar for a nuclear attack—and the U.S. went on high alert, even though Khrushchev was in New York City at the United Nations at the time.

In 1967 NORAD thought a solar flare was Soviet radar jamming, and nearly launched its bombers.

In 1979 the loading of a training scenario onto an operational computer led NORAD to call the White House, claiming that the U.S.S.R. had launched 250 missiles against the United States, and that the president had only between 3 and 7 minutes to decide whether to retaliate. In 1983 Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov refused to classify an early warning system missile sighting as an attack, dismissing it (correctly) as an error, and thereby preventing a worse error. And in 1995 Russian President Boris Yeltsin opened his nuclear weapons control briefcase when the launch of a Norwegian northern lights-studying rocket was interpreted as an attack.

In 1983 the Red Air Force mistook an off-course Korean airliner carrying 100 people for one of the U.S. RC-135 spy planes that routinely violated Russian air space to test Soviet air defenses, and shot it down.

In 1988 the U.S. Navy cruiser Vincennes—at the time in Iranian territorial waters without Iran’s permission—shot down on on-course Iranian airliner carrying 290 people.

Sometimes the Cold War went badly. Sometimes very badly. And sometimes it threatened to go very, very badly indeed.

It is salutary to admit that the Cold War could have ended otherwise. Why didn’t it? People could and did make a difference. Those who made the greatest difference were, I think, those who (a) kept the Cold War from getting hot, (b) persuaded many who wanted to keep fighting it that it was over, and (c) worked hardest to make the social democratic western alliance its best self.

Here is my list of the ten on the western side of the Iron Curtain who I think did most to make it so:

Harry Dexter White: Treasury Assistant Secretary who was the major force behind the Bretton Woods Conference and the institutional reconstruction of the post-World War II world economy. He accepted enough of John Maynard Keynes's proposals to lay the groundwork for the greatest generation of economic growth the world has ever seen. It was the extraordinary prosperity set in motion by the Bretton Woods' System and institutions--the "Thirty Glorious Years"--that demonstrated that political democracy and the mixed economy could deliver and distribute economic prosperity.

George Kennan: Author of the "containment" strategy that won the Cold War. Argued—correctly—that World War III could be avoided if the Western Alliance made clear its determination to "contain" the Soviet Union and World Communism, and that the internal contradictions of the Soviet Union would lead it to evolve into something much less dangerous than Stalin's tyranny.

George Marshall: Architect of victory in World War II. Post-World War II Secretary of State who proposed the Marshall Plan, another key step in the economic and institutional reconstruction of Western Europe after World War II.

Arthur Vandenberg: Leading Republican Senator from Michigan who made foreign policy truly bipartisan for a few years. Without Vandenberg, it is doubtful that Truman, Marshall, Acheson, and company would have been able to muster enough Congressional support to do their work.

Paul Hoffman: Chief Marshall Plan administrator. The man who did the most to turn the Marshall Plan from a good idea to an effective aid program.

Dean Acheson: Principal architect of the post-World War II Western Alliance. That Britain, France, West Germany, Italy, and the United States reached broad consensus on how to wage Cold War is more due to Dean Acheson's diplomatic skill than to any single other person.

Harry S Truman: The President who decided that the U.S. had to remain engaged overseas—had to fight the Cold War—and that the proper way to fight the Cold War was to adopt Kennan's proposed policy of containment. His strategic choices were, by and large, very good ones.

Dwight D. Eisenhower: As first commander-in-chief of NATO, played an indispensable role in turning the alliance into a reality. His performance as President was less satisfactory: too many empty words about "rolling back" the Iron Curtain, too much of a willingness to try to skimp on the defense budget by adopting "massive retaliation" as a policy, too much trust in the erratic John Foster Dulles.

Gerald Ford: In the end, the thing that played the biggest role in the rise of the dissident movement behind the Iron Curtain was Gerald Ford's convincing the Soviet Union to sign the Helsinki Accords. The Soviet Union thought that it had gained worldwide recognition of Stalin's land grabs. But what it had actually done was to commit itself and its allies to at least pretending to observe norms of civil and political liberties. And as the Communist Parties of the East Bloc forgot that in the last analysis they were tyrants seated on thrones of skulls, this Helsinki commitment emboldened their opponents and their governments' failures to observe it undermined their own morale.

George Shultz: Convinced Ronald Reagan—correctly—that Mikhail Gorbachev's "perestroika" and "glasnost" were serious attempts at reform and liberalization, and needed to be taken seriously. Without Shultz, it is unlikely that Gorbachev would have met with any sort of encouragement from the United States—and unlikely that Gorbachev would have been able to remain in power long enough to make his attempts at reform irreversible.

All honor to them—and to their peers on the other side of the hill.

Well one should include 1961 Goldsboro B-52 crash where we bombed ourselves but fortunately the safety switches held; it's not clear what would have followed if one of the bombs had gone off.

And one really should give all credit to Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov for disobeying orders in 1983 in order to forestall a retaliatory strike, and Vasili Alexandrovich Arkhipov, the 2nd in command on the Soviet nuclear submarine in 1962 who refused to sign off on his commander's order to launch their nuclear torpedoes. We should perhaps have national holidays in their honor as we would not otherwise be here.

Presumably other incidents were kept out of the public eye.

This is why we need to completely dismantle the US nuclear weapons system, down to the level of China's (which is 290 warheads, not loaded onto missiles). Russia will follow if we move first and are loud about it; everyone knows nukes are no good. Right now there is too much possibility of accidents, though certainly less than in the days of the deranged Curtis LeMay.