America's Past Deficits & Current Debt Are Very Unlikely to Be a Problem; But Future Deficits Might...

The true shape of America’s debt & deficit problems: a teaser. I am writing a piece for the Milken Review on the true shape of America's debt & deficit problem... or maybe opportunity—it depends...

The true shape of America’s debt & deficit problems: a teaser. I am writing a piece for the Milken Review on the true shape of America's debt & deficit problem... or maybe opportunity—it depends whether we use the exorbitant privilege of the U.S. Treasury for good of for evil…

For the full thing, check back at the Milken Institute Review in a couple of months: <https://www.milkenreview.org/> <https://milkeninstitute.org/>…

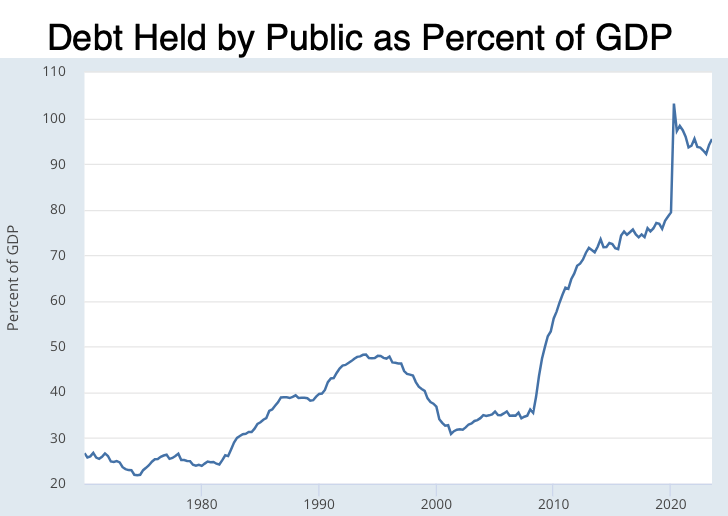

Exploding Debt since 1981:

Federal debt held by the public reached a low point as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product reached a low point of 21.9% in the third quarter of 1974. When Ronald Reagan’s first budget-year began, in the fourth quarter of 1981, it had ticked up to 25.2%. After the Reagan-Bush years, President Bill Clinton’s first budget-year saw debt-to-GDP at 48.2%. Clinton and Gore moved mountains—and permanently alienated the left-wing of the Democratic Party—to assemble Democrat-only legislative coalitions to leave George W, Bush with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 31.9%. George W. Bush and his people promptly blew it up again: it was 53.5% at the start of President Barack Obama’s first budget-year at the end of 2009. In spite of Obama’s prioritizing attempting to strike a “grand bargain” with Republicans on the deficit and debt over restoring full employment, it stood at 74.0% at the start of Trump’s first budget-year.

Debt-to-GDP reached a peak of 103.2% in the middle of the COVID plague in mid-2020. It stood at 94.0% at the start of President Joe Biden’s first budget-year. And it stands at 95.4% today

The runup of the debt-to-GDP ratio by 23.0%-points under Reagan-Bush budgets, the reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio—a change of -16.3%-points—under Clinton budgets. The runup of 21.6%-points under Bush II budgets. The runup of 20.5%-points under Obama budgets. The runup of 29.8%-points under Trump budgets. And most recently the runup—so far—of 1.4%-points under Biden budgets.

What Are the Implications?:

Just what is going on? Just what has been going on since the early 1980s? And how will this, eventually, all come to tears? What kind of tears will it come to?

My view: There is no reason for the debt we have accumulated so far to come to tears. The United States is a very attractive place for people all over the world to lend money too. The economy of the United States is a mighty wealth engine. And the U.S. government could tax that wealth at much higher rates than it does currently whenever it should wish to. Thus America can borrow at low enough interest rates that its debt accumulates so far is simply not a problem. The United States since at least 1896 is better viewed not as a place that has to pay moneylenders in order to borrow, but rather as a place in which savers are happy to park their money and pay for the privilege in order that they can be confident that it will be safe—in a nutshell, a modern-day analogue to the mediæval Medici Bank.

Thus if the United States can roughly much government program spending to taxes in the future while it rolls over its debt as it matures and borrows more money to pay the interest, the debt is highly likely to gradually diminish, and eventually fade away. Such a policy is a “deficit gamble”, but it is one on very favorable terms.

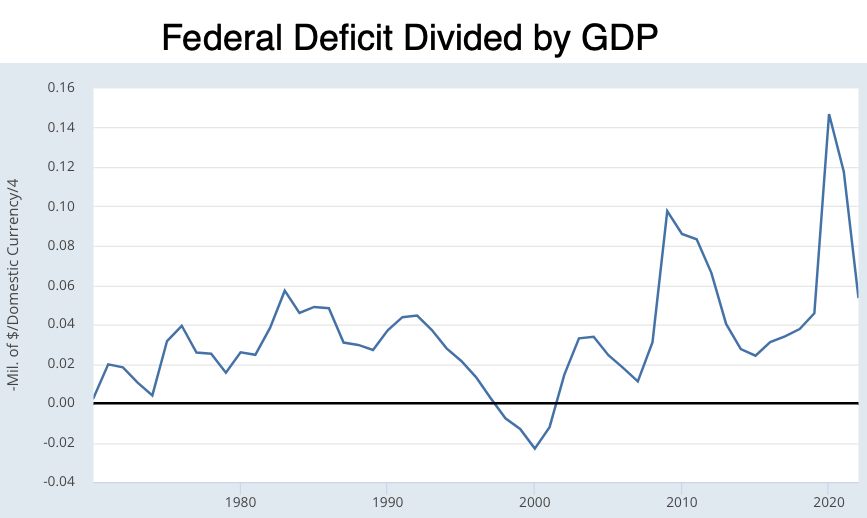

That is if the United States matches program spending to taxes: attains an average level of zero for what economists call the primary deficit.

That does not mean a balanced budget. It means borrowing more only to pay the interest owed on what had been borrowed before. It means a current-cash deficit of around 3% of GDP—of approximately $800 billion a year

But there is a problem here: Our current deficit is $1.7 trillion a year—not 3% but 6% of GDP—with no prospects I see even on the most distant horizon of a legislative coalition to reduce it to $800 billion, 3%. That is a big problem. In my view, it may well all end in tears—but, if so, not because of the deficits we have run in the past, but because of the deficits our broken political economy will produce in the future…

I have always been fascinated by the issue of government borrowing ever since I made my first really big purchase and took out a mortgage on a house. When buying a home, one is considered prudent if one spends only 1/3 of one's income to cover the necessary borrowing. One is expected to pay the debt down, slowly at first, then more quickly until the debt is completely retired. Then, one is expected to die after some years of being debt free.

In contrast, the government is not expected to die. We do not expect the trumpets to sound and Uncle Sam to be called before the great presence, who looks suspiciously like Milton Friedman, and be judged for his outstanding debt before facing his final moments.

So, is spending 1/3 of one's income on debt service an example of prudence or profligacy? Are governments just like households in their ability to manage debt or are they something different?

I think the best argument for the government spending less on debt than a 25 year old college graduate moving into a modest ranch house with his 26 year old girlfriend is that Uncle Sam cannot lock in an interest rate for the remainder of his expected life span as he does not have an expected life span. Mortality, I'll argue, does have some advantages.

Another good argument is that governments need to maintain a buffer of credit bearing capacity, so borrowing less than a reasonable 1/3 during less challenging times leaves room for borrowing more during more challenging times. This is a weaker argument since governments can increase their incomes during challenging times by raising taxes.

I think that "debt" is not the right variable to wish to manage. "Deficits" are closer to it, but even that is not right. The proper decisions are made at the level of taxing and spending. If we spend on things with present costs and future benefits such that NPV>0 the resulting deficit and whatever debt those deficits accumulate to can't be a problem. [There is a corresponding rule for taxing, but it's more complicated, involving whether the tax reduces consumption or investment and the NPV of the investments foregone, but I do not know how to state it.]

I AM sure that "debt" is not an argument in either the taxation or expenditure optimization functions, although it could indirectly enter by affecting the discount rate applied to the NPV.

Of course this does not mean that YOU should not try to disabuse the Milken audience of notions that are even more wrong than failing to make the NPV of expenditures >0. In particular you should try to direct their attention to revenue raising rather than expenditure reduction as a response for whatever worries about debt or deficits they have.