The Unmaking of a Modern Economy: Brexit, Austerity, and Britain's Great Retraction

Austerity's False Economy? Brexit's Blow? The Long Shadow of 2008? You need much more than those to account for Britain's pitiful economy since Nick Clegg decided to let the Tories govern the place...

Austerity's False Economy? Brexit's Blow? The Long Shadow of 2008? You need much more than those to account for Britain's pitiful economy since Nick Clegg decided to let the Tories govern the place…

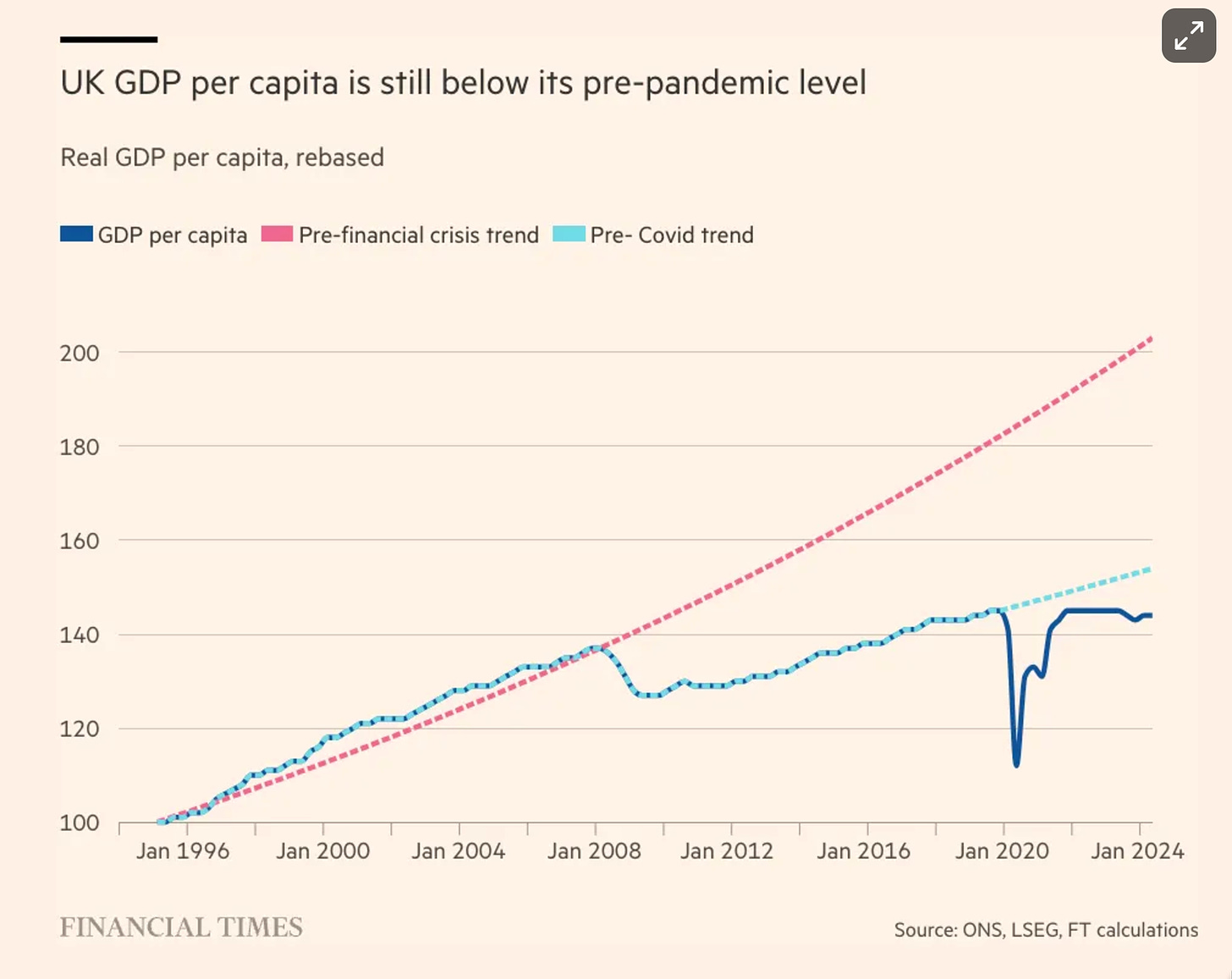

What happens when a global financial hub bets on the wrong policies at the wrong time? Britain's story since 2008 is one of lost potential, economic stagnation, and repeated grave self-inflicted wounds. And even those are not enough to account for it, even as we pile policy missteps on top of structural failures. Had Britain maintained its pre-2008 growth trajectory, it would be 40% richer today…

Every time I look at this or analogous graphs, I am dumbfounded anew:

How can you do this to a rich Dover-Circle-Plus—indeed, the original, the ur-Dover-Circle-Plus—market economy in a time of real technological revolution?

I mean, yes, Tories (and LibDems) bad and stupid, austerity stupider, and BREXIT stupidest yet. And, yes, something similar happened to Italy. But, still, had Britain continued on its pre-2008 growth trend it would now be forty percent richer than it is today. That is £11,000 per capita per year.

Yes, the GFC, the Great Recession, and the subsequent Anæmic Recovery did a dance on an economy that was and is heavily finance-dependent, and can maybe account for £3,000 of that. Yes, BREXIT can plausibly account for £2,000. And austerity for £1,500 more. But to have nothing go right? And we are pushing the envelope—relying a lot on the appeal to hysteresis—to get up to 2/3 of the total.

Those parts of the 2024 Michael Chea Harvard Kennedy School Macroeconomics Conference, & Larry Summers 70th Birthday Party that I was mostly interested in focused on three things:

Noise traders: Larry Summers’s 1984 insight—which cannot have been original to him by the laws of probability, but which I cannot find anyone saying before and which he pushed very hard on—that Milton Friedman’s claim that “noise traders” lose money and so over time become negligible players in a speculative market is simply wrong. Their utility will be lower. But to the extent that they create (priced) risk which they then must inevitably bear a lot of or bear other (priced) risks they simply do not understand, their returns will be higher. It is certainly true—as Robert Waldmann taught me—that the odds are overwhelmingly large that any individual “noise trader” will go spectacularly bankrupt, but the aggregate share of money held by noise traders will grow (and the richest among them acclaimed as true geniuses, and worshipped). This, we believe, is likely to have very powerful implications.

What Larry miscalls “secular stagnation”—it is not a source of profitable investment opportunities and thus of possibilities for capital-intensive capital-using growth, it is rather Valery Giscard d’Estiang’s “exorbitant privilege” in the sense of the very strong and excessive demand for “safe assets”, where safe assets is a term of art—for the assets are not really safe, but are conventionally accepted as and are valued as if they were.

What Larry and Olivier Blanchard miscall “hysteresis”—temporary shocks that have large permanent effects, but only very tangentially related to the magnetic or elastic processes. Our best paper on this is, I think, universally agreed to be . But I think that “How Does Macroeconomic Policy Affect Output?” is not bad either.

The British experience since Nick Clegg began to conduct his natural experiment on the long-run effects of austerity policies guided by stupidity and xenophobia by deciding to hand the baton to the Tories back in 2010 is a very strong point on the pro-hysteresis side.

In fact, as I think back over history. There are only two cases in America at least where one points to big shocks and does not see permanent depressing effects on the economy: the Great Contraction of 1929 to 1933 and the Covid Plague of 2000. Both were neutralized later on, the long-run effects of Great Contraction by the mobilization for World War II, and those of the Covid Plague by the $1.9 trillion Biden-administration American Rescue Plan. So I do not really see these two episodes as counting against the concept.

And the post-GFC British experience certainly weighs enormously in the balance in favor of it.

More about the other two anon…

References:

Cribb, Jonathan, & Paul Johnson. 2018. "10 Years On – Have We Recovered from the Financial Crisis?" September 12. <https://ifs.org.uk/articles/10-years-have-we-recovered-financial-crisis>.

DeLong, J. Bradford, Andrei Shleifer, Lawrence H. Summers, & Robert J. Waldmann. 1990. "Noise Trader Risk in Financial Markets." Journal of Political Economy 98 (4): 703–738. <https://econpapers.repec.org/article/ucpjpolec/v_3a98_3ay_3a1990_3ai_3a4_3ap_3a703-38.htm>.

DeLong, J. Bradford, & Lawrence H. Summers. 2012. "Fiscal Policy in a Depressed Economy." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2012 (1): 233–297. <https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/2012a_DeLong.pdf>.

DeLong, J. Bradford, & Lawrence H. Summers. 1988. "How Does Macroeconomic Policy Affect Output?" Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1988 (2): 433–494. Accessed at <https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/1988/06/1988b_bpea_delong_summers_mankiw_romer.pdf>.

Emmerson, Carl, Paul Johnson, & Nick Ridpath. 2024. "A Decade and a Half of Historically Poor Growth Has Taken Its Toll." Institute for Fiscal Studies. June 3. <https://ifs.org.uk/news/decade-and-half-historically-poor-growth-has-taken-its-toll>.

Friedman, Milton. 1953. "The Case for Flexible Exchange Rates." In Essays in Positive Economics, 157–203. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. <https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/spring/summer-2018/milton-friedman-case-flexible-exchange-rates-monetary-rules>

Fisher, Lucy, & Martin Wolf. 2024. “Why I’m Worried”. Political Fix Podcast. October 14. <https://www.ft.com/content/3e504036-e9ee-4757-baf9-47fdccbf340c>.

Murphy, Richard. 2023. "There Is a Way Out of Stagnation. It's Not Hard to Work Out. It Could Be Delivered. But First of All, We Have to Care About Each Other. Is That Possible?" Tax Research UK, December 6. <https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2023/12/06/there-is-a-way-out-of-stagnation-its-not-hard-to-work-out-it-could-be-delivered-but-first-of-all-we-have-to-care-about-each-other-is-that-possible/>.

Starmer, Keir. 2024. "Keir Starmer Meets BlackRock Boss Larry Fink in Downing Street." Financial Times, November 21, 2024. https://www.ft.com/content/b2279b03-320f-4dec-b241-a755d36c7b9e.

Thompson, Derek. 2022. "How the U.K. Became One of the Poorest Countries in Western Europe." The Atlantic. October 25. <https://www.theatlantic.com/newsletters/archive/2022/10/uk-economy-disaster-degrowth-brexit/671847/>.

Weston, Thomas. 2023. "Economic Growth, Inflation and Productivity." House of Lords Library. June 28. <https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/economic-growth-inflation-and-productivity/>.

Martin Wolf. 2023. "UK Desperately Needs an Economic Growth Strategy." The Irish Times, December 13. <https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/2023/12/13/uk-desperately-needs-an-economic-growth-strategy/>.

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…

It has been observed many times that modern Economics doesn't have a model, or in most cases even a variable, for social power. Perhaps the root cause is that there are powerful people in the UK who don't want the nation to be 11,000/person wealthier if that wealth will be somewhat evenly spread around the population and not 95% to themselves. It is more fun to rule as Duke over a population that is weak and beholden to you even if costs you a bit of absolute wealth - or so some people think.

The divergence between New Zealand and Australia is striking evidence for the persistent effects of recessions. NZ had a string of recessions after 1990 (Don Brash played a big role here) while Australia went 20 years without one. While the two countries grew in parallel for most of C20 NZ is now much poorer and the gap is widening even now.