Tim Duy of SGH Macro Advisors Also Thinks the Fed Is Behind the Curve on Easing

The December employment report shows, to me at least, no signs that it is not time to get the band back together! What should be the band's new name? Team Expansionary?...

The December employment report shows, to me at least, no signs that it is not time to get the band back together! What should be the band's new name? Team Expansionary?…

Steady-as-she-goes with the December Employment Report <https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm>:

Total nonfarm payroll employment increased by 216,000 in December…

Employment continued to trend up in government, health care, social assistance, and construction, while transportation and warehousing lost jobs…

The unemployment rate was unchanged at 3.7 percent…

The labor force participation rate, at 62.5 percent, and the employment-population ratio, at 60.1 percent, both decreased by 0.3 percentage point in December…

Average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 15 cents, or 0.4 percent, to $34.27…

Over the past 12 months, average hourly earnings have increased by 4.1 percent…

Average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees rose by 10 cents, or 0.3 percent, to $29.42.

Seasonal adjustment factors, of course, make even the limited information contained in the eye-dropper drop that is one month’s employment report cloudy. And if you are convinced that the (a) profit share must always stay stable or increase, and (b) must never decrease, plus (c) productivity growth is relatively low, you might see a reason for the Fed not to cut interest rates in (5) and (6) (although not (7)).

But labor statistics are lagging indicators. And if policy right now is indeed substantially restrictive, employment reports showing labor-market weakness will come. It is only a matter of time.

Tuesday morning in my email inbox I found Tim Duy of SGH Macro Advisers (for pay only, but very much worth following if monetary policy month-by-month is your jam) writing:

Tim Duy: Fed Watch: ‘The Fed believes… maintaining… current… rates will be too restrictive…. Powell has long argued… [for] cutting rates before inflation returns to 2% to prevent… unnecessary [demand] weakness. By that metric it appears the Fed is well behind the curve…. Labor data lags, and waiting for softer data guarantees overshooting. The path of least resistance… is to cut rates 25bp at every meeting beginning in March, which would total 175bp for the year, just a notch above the roughly 150bp already priced into markets…

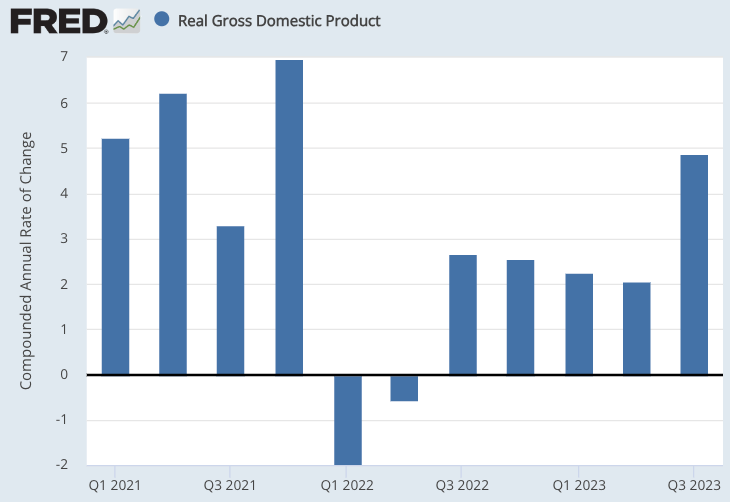

Is this right? As we saw Friday morning, no sign of labor-market weakness. And no signs of weakness in real aggregate demand since the first half of 2022:

Well, that depends.

Is Tim saying that this is what the Fed should do? Or is he saying that this is what the Fed will do. If the first, I think he is right. If the second, I am not so sure—especially because there are participants in FOMC meetings who will make a big fuss about earnings-growth numbers and will threaten to dissent from a rate-cut decision in January, or even March.

As to this being what the Fed should do, I find the arguments airtight:

Preemptive Action Against Economic Weakness: Cutting rates before inflation hits 2% can help prevent unnecessary economic slowdown, aligning with Jerome Powell’s long-standing argument.

Mitigating Risks of Recession: Recession is a special danger to be avoided whenever you can, for lots of things change in a recession—and not for the better. Growth below potential for an extended time is vastly to be preferred when “cooling off” is in some sense called for.

Avoiding Overshooting in Labor Market Adjustments: This is especially the case for the labor market. Given the lag in labor data, early rate cuts can help the Fed avoid the truly significant economic disruptions that happen when the labor market changes state—when firms decide: “we are in a recession, and so now we have an excuse to slim down our labor force and fire poor-performing workers because in a recession we can claim we are doing so out of necessity, not just because we are greedy assholes”.

Aligning with Market Expectations: The Fed's approach that Tim Duy wants to see/expects to see is only slightly more aggressive than what is already priced into the markets (175bp vs. 150bp). It is in line with current economic sentiment. And when you have a choice among policies that are all nearly equivalent, the one that causes the least surprise and creates the least uncertainty is to be preferred.

But will the Fed in fact cut interest rates by 25bp seven times in 2024?

The argument that really should be dispositive starts with the observation that when the economy is in neutral—inflation near 2%/year with no big pressures pushing it up or down—policy should be in neutral as well—with interest rates at their neutral rates. And it observes that next to no one thinks neutral rates are as high as interest rates are now.

Will this argument be convincing? I am not convinced it will be.

Why wait until March?

I assume that if the Fed starts cutting rates, Republicans will scream that it's part of a plot to make the economy better, to help Biden. (As opposed to, you know, making the economy better to help _Americans_, generally.)