I greatly enjoy and am, in fact, driven to write Grasping Reality—but its long-term viability and quality do depend on voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. I am incredibly grateful that the great bulk of it goes out for free to what is now well over ten-thousand subscribers around the world. If you are enjoying the newsletter enough to wish to join the group receiving it regularly, please press the button below to sign up for a free subscription and get (the bulk of) it in your email inbox. And if you are enjoying the newsletter enough to wish to join the group of supporters, please press the button below and sign up for a paid subscription:

Suppose one were to take this seriously:

Karl Marx: The Poverty of Philosophy: ‘Men make cloth, linen, or silk materials in definite relations of production. But… social relations are just as much produced… are closely bound up with productive forces. In acquiring new productive forces, men change their mode of production… the way of earning their living… all their social relations. The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist…. Social relations [are] in conformity with… material productivity….Principles, ideas, and categories [are] in conformity with… social relations…. Ideas… [and] categories… are historical and transitory products…

LINK: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/subject/hist-mat/pov-phil/ch02.htm>

The rate of technological advance is itself a product of the shape of society. But in return the level of technology, and the speed and direction at which that level is advancing, greatly shape the upper layers of the economy, and then political economy and economic sociology, as well, from which consequences ramify. How are we to get a handle on this?

The first attempt to get a handle on this was, of course:

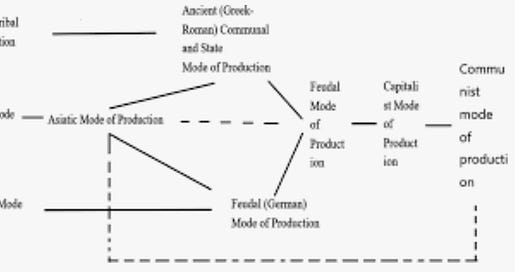

Karl Marx: Preface to “A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy”: ‘In broad outline, the Asiatic, ancient, feudal and modern bourgeois [or, alternatively, tribal, ancient, feudal, bourgeois] modes of production may be designated as epochs marking progress in the economic development of society…

LINK: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1859/critique-pol-economy/preface.htm>

But surely we can do better now?

I have my exceptionally crude index of the value of the stock of human “technology”—the useful ideas about manipulating nature and productively organizing humans that have been discovered, developed, deployed, and diffused throughout the global economy. It is simply equal to the estimated (or guessed) average worldwide level of real income per capita times the square-root of the population, with the square-root to take account for the fact that because resources are scarce feeding and housing more people requires better technology, but because each human comes with ten fingers, eyes, a mouth, and a brain, humans are productive.

My index, normalized at a global level of 1.0 in 1870—in the Steampower Age, just after Marx published the first volume of his Capital—for the value of the stock of useful human ideas for manipulating nature and productively organizing humans, is equal to 1/3 back in 1000, when feudalism was well-established (at least between the Rhine and the Loire).

Suppose we view that big a jump—a tripling—as indicative of a change in the “mode of production”: as a big enough shift in underlying technologies that are then embodied in the forces of production to make it sensible to put a stake in the ground, and to then say that that stake marks a fundamentally different kind of society than humans had when my technology index had been only one-third as large.

Then, if we take each tripling of that index as marking a shift in the “mode of production”, we get:

2020: Global-Manufacturing mode of production

1970: Mass-Production mode of production

1920: Second-Industrial-Revolution mode of production

1870: Steampower mode of production

1000: Feudal mode of production (and maybe you also want to say “Asiatic”)

-1500: Bronze-Literacy mode of production (what Marx thought of as “ancient” has its center of gravity about halfway between Bronze-Literacy and Feudal)

-8000: Gatherer-hunter mode of production

Does this make sense?

We could say “no”—that, rather, the important things are not modes of production but modes of domination. One would then want to mark the Babylon-Mycenæ-Troy triad before -1000 as one system, and the Athens-Sparta-Rome triad around -200 as another, before moving on to Feudalism in 1000 as we knew it as a third. And then, presumably, we would want to insert Gunpowder Empires between Feudalism and Steampower, and back away from an exclusive focus on technological underpinnnings—hand-mills and steam-mills—and grant autonomy and agency to modes of appropriation and distribution. Before 1870, not x3 but rather x√3 seems better to me, which would give us:

2020: Global-Manufacturing mode of production

1970: Mass-Production mode of production

1920: Second-Industrial-Revolution mode of production

1870: Steampower mode of production

1550: Gunpowder-Empire mode of domination

1000: Feudal mode of production (and maybe you also want to say “Asiatic”)

-300: Ancient mode of domination

-1500: Bronze-Literacy mode of production (what Marx thought of as “ancient” has its center of gravity about halfway between Bronze-Literacy and Feudal)

-4000: Tribal mode of production

-8000: Gatherer-hunter mode of production

I could live with that…

Then there is the question of what to do with time after 1870—the problem which has its origins in Charlie from Trier and Freddie from Barmen mistaking the birth pangs of industrial capitalism for its death throes. In terms of humanity’s ability to manipulate nature and productively organize humans, the world of 1920 was as much more powerful than the world of 1870 than the world of 1870 had been than the world of 1000. And the world of 1970 was an equivalent relative gap more advanced than 1920 still. And for our world of 2020 the relative gap is the same.

Do we then have a succession of three different “modes of production” between 1870 and today?

The Marxists are of absolutely no help here. The old Marxists flattened everything after 1800 into “capitalism”, with perhaps an admission that, recently, things have been different: “late capitalism”. The new Marxists have made themselves take the “cultural turn”, and have disappeared into the swamp of discursive idealism. (Recall how extremely nasty were the things Marx himself had to say about those who in his day had taken the “cultural turn”.) The sociologists are also of little help. They tend to say that the big watershed-boundary crossing happened once and only once: industrial rather than artisan production, class rather than estate-status, urban rather than rural, bureaucratic rather than personal governance, science rather than faith, progress rather than the wheel of fortune, contractual rather than ascribed relationships, Malthusian rather than post-demographic transtion, and the societal game-board being upset and pieces repositioned every generation as opposed to seen as static and natural—one big shift, in “complex" societies, at least, from traditional to modern.

Certainly the forces of production of today’s Global-Manufacturing economy are sufficiently different from 1970’s “Fordist” Mass-Production economy, which are different from 1920’s Second-Industrial-Revolution economy which are different from 1870’s Steampower economy. But there is a sense in which people think that between today and 1870—or maybe only between today and 1920—the relations of production are pretty much the same: people exchange goods and services for money in transactions that are at least notionally arms-length, have property, most people work for wages for bosses, and the rest collect interest, profits, and rent; meanwhile a literate citizenry engages in politics and people typically choose their mates and thus their families. Life back in 1900 appears to have been both modern, and not.

And then there is the question of whether there have been even bigger changes in the information-entertainment-cultural superstructure than even in the forces of production…

Clearly here is another set of issues, about which I need to think more deeply. That is anxiety inducing, since in a month and a half I am publishing a book that will lead people to ask me lots of questions, many of them assuming I have already thought all these issues through to my satisfaction…

I noticed today that there is a new book out: James Belich, The World The Plague Made (Princeton 2022). It concerns the effects of The Black Death and its aftermath on the economic development of Western Europe, specifically the impact of such a sudden, massive population loss on economic development in succeeding centuries. I believe I also recently saw a reference to a book or journal article making the case that the population loss was not as large as has long been assumed.

You may have covered this topic somewhere, but I did wonder how the Black Death fits into your timeline for our escape from the Malthusian treadmill. Was it a short, sharp shock that didn’t have much of an effect on the long-term trend line, or was it a significant or even essential precondition to our eventual escape?