Trying to Think Through Our Crisis of Liberal Democracy, Part I

Þis was supposed to be a review of Martin Wolf's "The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism", but I have gotten very distracted indeed...

The Financial Times’s Martin Wolf wrote to me:

My new book, The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism <https://www.amazon.com/dp/0735224218>, is a relatively slight effort. But I would welcome your reactions…

He is wrong: it is definitely not a slight effort. In this case, at least, the British mode of modesty and self-deprecation is simply misleading.

So I decided to take up the invitation. And I got distracted. So here is Part I: 1600 words of throat clearing:

Lessons of Ancient History for Democratic Stability

Start with the proposition that even a semi-stable democracy is a new thing under the sun.

The historical record was such that the founders of modern democracy felt themselves very much arguing against the grain in asserting that the voyage was worth undertaking. For example, consider Alexander Hamilton, in The Federalist 9 <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0162>:

It is impossible to read the history of the petty republics of Greece and Italy without feeling sensations of horror and disgust… the rapid succession of revolutions… perpetual vibration between the extremes of tyranny and anarchy…. From the disorders… the advocates of despotism have drawn [their] arguments…. [And] it is not to be denied that the portraits they have sketched of republican government were too just copies of the originals from which they were taken…

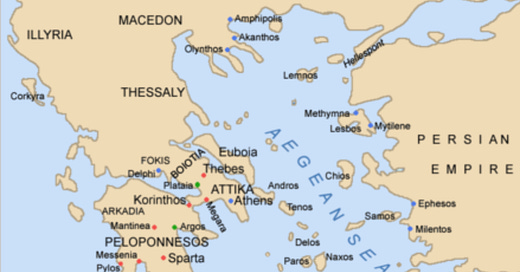

What is Hamilton talking about? Among many other things, this account of the Mytilene Debate in the Athenian Assembly in the year –427, from Thoukydides’s The Peloponnesian War 3.36–49 <http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/readings/thucydides6.html>:

The Athenians… in the fury of the moment determined to put to death… the whole adult male population of Mytilene, and to make slaves of the women and children…. They accordingly sent a galley… commanding [General Paches at Mytilene] to lose no time in dispatching the Mytilenians. The morrow brought repentance with it, and reflection on the horrid cruelty of a decree, which condemned a whole city to the fate merited only by the guilty. This was no sooner perceived by the Mytilenian ambassadors at Athens and their Athenian supporters, than they moved the authorities to put the question again to the vote….

Cleon… who had carried the former motion of putting the Mitylenians to death, the most violent man at Athens, and at that time by far the most powerful with the commons…. Diodotus… who had… in the previous assembly spoken most strongly against putting the Mytilenians to death…. The Athenians… the show of hands was almost equal, although the motion of Diodotus carried the day. Another galley was at once sent off in haste, for fear that the first might reach Lesbos in the interval, and the city be found destroyed; the first ship having about a day and a night’s start.

Wine and barley-cakes were provided for the vessel by the Mytilenian ambassadors, and great promises made if they arrived in time; which caused the men to use such diligence upon the voyage that they took their meals of barley-cakes kneaded with oil and wine as they rowed, and only slept by turns while the others were at the oar. Luckily they met with no contrary wind, and the first ship making no haste upon so horrid an errand, while the second pressed on in the manner described, the first arrived so little before them, that Paches had only just had time to read the decree, and to prepare to execute the sentence, when the second put into port and prevented the massacre. The danger of Mytilene had indeed been great…

A government that can decide to massacre a city on Monday and then reverse that decision on Tuesday is truly a chaos monkey.

Nevertheless, the founders of our democracy were willing to undertake the venture. Hamilton, for example, promised his readers that the prospects for success of democracy in America were actually quite good, for:

The science of politics…, has received great improvement… distinct departments… legislative balances and checks… judges holding their offices during good behavior… representation of the people… are means, and powerful means, by which the excellences of republican government may be retained and its imperfections lessened or avoided…

But how much did Hamilton really believe this? Thomas Jefferson—a genuine true believer in democracy, at least of a certain sort—was confident that Hamilton was not saying what he believed but, rather, merely talking his book. And Jefferson wrote in 1814 that he suspected that George Washington himself had more than half-agreed with Hamilton, and saw the success of American democracy as not that likely. See Thomas Jefferson: to Walter Jones, 2 January 1814 <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-07-02-0052>:

Gen’l Washington had not a firm confidence in the durability of our government… and I was ever persuaded that a belief that we must at length end in something like a British constitution had some weight in his adoption of the ceremonies of levees, birth-days, pompous meetings with Congress, and other forms of the same character, calculated to prepare us gradually for a change which he believed possible, and to let it come on with as little shock as might be to the public mind…. He considered our new constitution as an experiment on the practicability of republican government…. [But] he was determined the experiment should have a fair trial…

Moreover, Jefferson’s political ally and successor as president James Madison saw the same problems. Here is Madison in Federalist 10 <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0178>:

A pure democracy… can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest… felt by a majority… there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual…. Such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths…

Larry Diamond’s Explanation of Our Current Discontents:

For 220 years it looked as though Hamilton, Madison, Jefferson, and Washington had been right—mostly: there was a big Civil War in the middle that killed 1/4 of adult white men in the Confederacy (and 1/15 of those in the anti-Confederacy Union)—to ultimately take counsel of their hopes rather than their fears.

But over the last 15 years, not so much.

What has gone wrong? When interviewed recently by Martin Wolf, Stanford’s Larry Diamond <https://www-ft-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/content/10151ecd-aa56-4ed0-aaf4-e7580b26e6bb> said that he thought our recent worldwide democratic retreat was due to five factors. As I understand his five factors, they are:

George W. Bush and Richard Cheney’s attack on Iraq in 2003—which convinced much of an increasingly anti-imperialist world that the U.S. used “democracy” as a veil to cover what a great power does, and that the U.S.’s real commitments were to the principle that the strong do what they will while the weak suffer what they must.

George W. Bush, Richard Cheney, Alan Greenspan, and Ben Bernanke’s lax enforcement of financial regulation which set the stage for the Global Financial Crisis—which demonstrated that neoliberal élites’ arguments that their market-heavy economic governance system might produce inequality but did so in exchange for stable prosperity.

(a) Barack Obama’s failure to prioritize rapid return to full employment in 2009, and then (b) the blockage of expansionary fiscal policy by Republican congressional majorities after 2010—which demonstrated that neoliberal élites lacked interest in rapidly restoring shared prosperity.

The rise of social media and its advertising revenue-fueled outrage-clickbait-attention mechanism, in the context of a humanity where it is easy to rally people against an alien and deviant enemy, but hard to get people to calm down and think about win-win governance.

Turkish strongman Erdogan’s discovering the road map to successfully attaining and retaining power by turning a liberal democracy into an illiberal soft authoritarian régime—and all the others from Trump and Bolsonaro to Modi and beyond who have picked up the playbook.

I hesitate to call (2) and (3b) policy mistakes: lax financial regulation was an important part of the policy package that greatly increased inequality, thus pleasing the plutocratic portion of the Republican base, and blocking a more-rapid recovery after 2010 did substantially reinforce Republican dominance (albeit it played a role in the Trump takeover of the Republican Party which led to most of the politicians who had blocked faster recovery over 2011–2016 being defenestrated). But they were certainly policy actions. (1) and (3a) were definitely mistakes. (5) was a political success, albeit a very malign one for the future of human flourishing.

Of all the factors adduced by Diamond, four are thus causally “thin”: important political decisions made by small groups with serious agency who could well have chosen otherwise. Only (4)—the technology- and market structure-driven rise of social media, and the derangement of the public sphere of political reason that it has brought—is in any way a structural, causally “thick” factor.

Thus if we buy Diamond, we seem to be impelled down one of two paths:

We have been very unlucky: after 220 years in which our political leaders have by and large chosen wisely (or wisely enough), we have had 15 years during which our political leaders have chosen sufficiently unwisely to crack if not shatter what had appeared for centuries to be a robust system, in fact the flood tide of history.

The modern internet and advertising-supported social media are a destructive social-communication medium the likes of which we have not seen before—save, perhaps, for the days when Gutenberg’s printing press ignited nearly two centuries of near-genocidal religious war in Europe.

Is that satisfactory? Are those in fact our choices for understanding here?

I think that it's important, at least in the US context, to mention the structural problems which impede both democracy and solutions to the crises: the Senate; the Electoral College; gerrymandering; a Supreme Court out of control in substantial part due to the foregoing. The first two of these were mistakes bequeathed to us by the Framers, the latter two partly resulting from the others and partly our own mistakes. Nor are these the only problems, but they are problems of the first order.

Aging demography may be a sixth factor. The age cohort peaking with Boomers are old enough to have lived in a whiter, more segregated society for which appeals to racism and nativism are most appealing, but are not old enough to have been indoctrinated against authoritarianism. Their media is cable, Facebook, and e-mail, which tends to be hijacked by conspiracy theories; younger generations consume streaming, Instagram, TikTock, etc. Younger people have experienced the lies and absurdity of social media in their personal interactions, and so are more critical of its content. Finally, the adults who still live in rural areas tend to be older because many younger ones went to the city for employment. Rural areas have out-sized political power (Senate, electoral college), so older people not only vote more, but their votes effectively count more.