Twenty-Five Theses on þe World-Historical Importance of 1870, &

BRIEFLY NOTED: For 2022-08-28 Su

I greatly enjoy and am, in fact, driven to write Grasping Reality—but its long-term viability and quality do depend on voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. I am incredibly grateful that the great bulk of it goes out for free to what is now well over ten-thousand subscribers around the world. If you are enjoying the newsletter enough to wish to join the group receiving it regularly, please press the button below to sign up for a free subscription and get (the bulk of) it in your email inbox. And if you are enjoying the newsletter enough to wish to join the group of supporters, please press the button below and sign up for a paid subscription:

FIRST: Twenty-Five Theses on the World-Historical Importance of 1870

The truest hinge of human history comes in 1870.

The true hinge of human history comes not with the 1070 investiture controversy or with 1450 Gutenberg-and-the-Renaissance, or with the 1700 Commercial-Enlightenment Revolution.

The true hinge of human history does not even come with the 1770 steam-and-machinery classic industrial revolution.

The true hinge of human history comes with the 1870 arrival of the last three pieces of the institutional configuration needed to support what Simon Kunznets labeled "modern economic growth”.

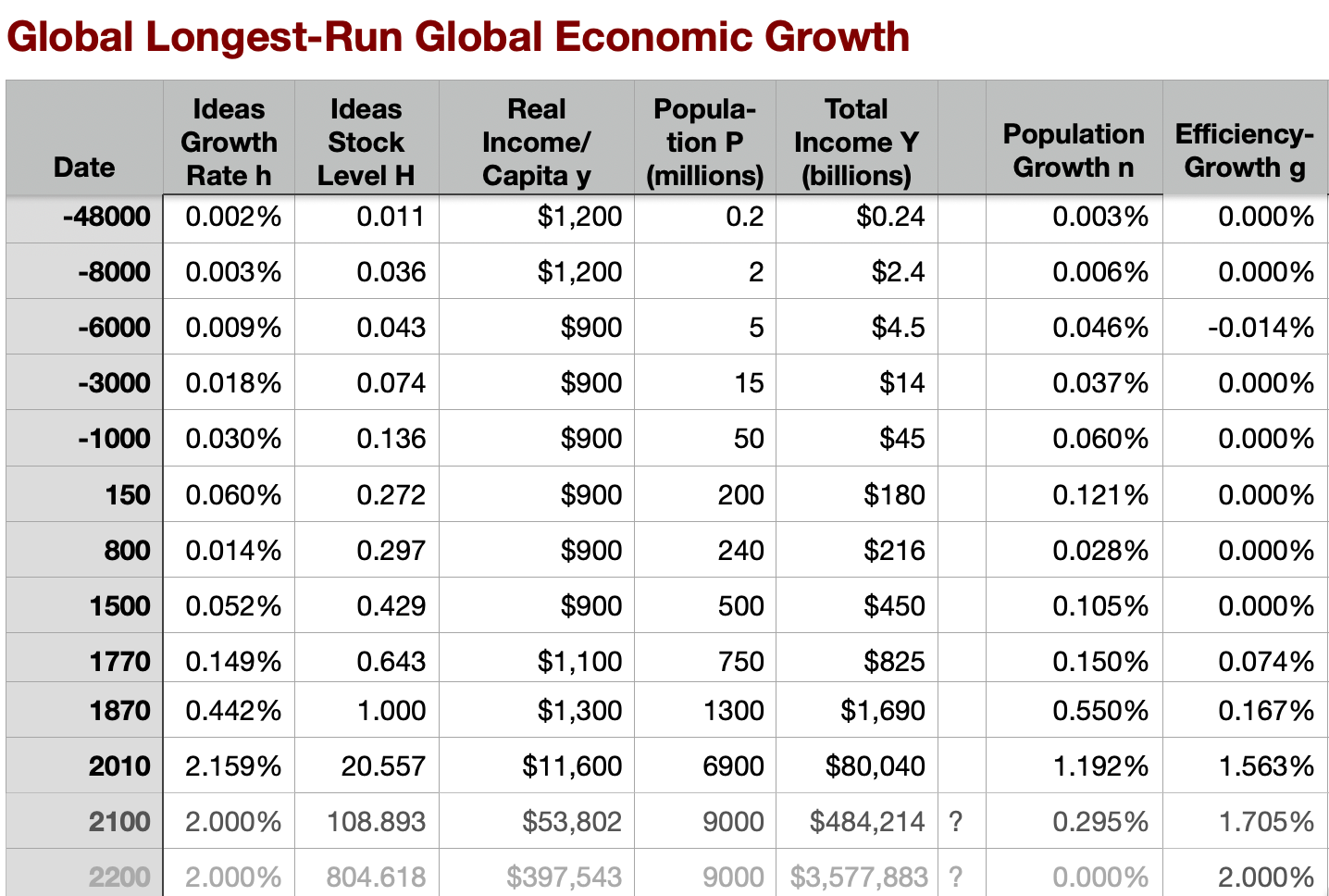

Modern economic growth's arrival was the at least 4.5-fold upward jump in the rate of progress in technology deployed globally—a jump to the 2.1% per year or more rate characteristic of the 1870-2010 long 20th century.

The "at least” and the “or more” from the fact that our attempts to calculate real incomes are almost always measures of factor cost, while what we really want are measures of user benefit. We can guess at a rule-of-thumb: that factor cost and user surplus are of similar orders of magnitude for most rival commodities. But we would not expect that rule-of-thumb to hold for non-rival commodities. And an increasing share of production is non-rival as technology advances.

The first of the three missing pieces of the institutional configuration that arrived in 1870 was the industrial research lab—making possible the rationalization and routinization of the discovery and development of better technology.

The second of the three missing pieces of the institutional configuration that arrived in 1870 was the modern corporation—making possible the rationalization and routinization of the development and deployment of better technology.

The third of the three missing pieces of the institutional configuration that arrived in 1870 was full globalization—in communications, in transportation, in migration, and in cultural contact—making possible and amping-up the incentives for the global deployment and diffusion of better technology.

Do not make the mistake of believing that the research lab, the corporation, and full globalization were the only or even the most important pieces of the institutional configuration.

But without the research lab, the corporation, and full globalization, we get a worldwide rate of growth of deployed-and-diffused technology of less than 0.5% per year.

With the rule of thumb that 2% more resource scarcity diminishes productivity by as much as 1% more technology increases it, a rate of growth of the value of the technology stock deployed-and-diffused of 0.5% per year can be neutralized by a population growth rate of 1% per year—a doubling only every three generations.

Why the rule of thumb that 2% more resource scarcity diminishes productivity by as much as 1% more technology increases it? That comes from a production function in which real income per capita is technology divided by the square root of population. To claim that real income per capita is simply proportional to technology makes the false claim that resource scarcity is not a thing. To claim that total global income is proportional to technology makes the false claim that labor is not productive. Real income per capita is technology divided by the square root of population—that is a middle ground.

If the rate of growth of technology is less than 0.5% per year—as it was before 1870—Malthusian positive and preventative checks swing into play to further limit the long-run growth of population.

A doubling of population every three generations is something that even a nutritionally stressed and poor (but not desperately poor) human population can and does accomplish—as long as patriarchy drives women to devote great effort to bearing sons.

Only a society undergoing modern economic growth can become wealthy enough to loosen patriarchy enough for women to possess durable forms of social power other than being the mothers of sons.

Thus before the coming of modern economic growth, the rate of technological progress was not fast enough to push real incomes high enough to trigger the demographic transition.

Before 1870 technology was not able to win its Malthusian race against fertility. That meant a very poor world, in which there was no prospect that a sufficiently large economic pie could be baked for everyone to have enough.

This was even true during the 1770 to 1870 classic industrial revolution century: the likely counterfactual scenario in which modern economic growth does not arrive after 1870 is of a very poor and semi-permanent steampunk world.

Before 1870, therefore, the overwhelming task of governance was that of running a force-and-fraud exploitation-and-extraction machine for the benefit of an élite, so that it could thereby appropriate enough for its members.

After 1870, the prospect of baking a sufficiently large economic pie comes into view—“economic El Dorado”, Keynes called it.

After 1870, therefore, the possibility arises of governance focused on guiding the creation of a truly human world.

A truly human world would be one in which there is baked a sufficiently large economic pie that is then sliced equitably so that everybody can have enough and that can be properly tasted—utilized to offer all of us lives that make us healthy, safe, secure, and happy.

Since 1870 we have managed to accomplish the task of baking, a sufficiently large, economic pie—one that is, in fact, vastly in excess of what earlier-century observers would have thought required to underpin a true utopia.

But the problems of slicing and tasting—utilizing—our now sufficiently large economic pie have flummoxed us.

Very Briefly Noted:

David Fickling: China’s Power Crisis Could Reach a Himalayan Scale <https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-08-23/china-s-hydro-power-cuts-could-herald-a-himalayan-scale-crisis-for-rivers-dams>: ‘The drought triggering power cuts along the Yangtze heralds a far bigger problem that may doom hydro projects across much of Asia…

Mike Masnick: Twitter Whistleblowing Report Actually Seems To Confirm Twitter’s Legal Argument, While Pretending To Support Musk’s <https://www.techdirt.com/2022/08/24/twitter-whistleblowing-report-actually-seems-to-confirm-twitters-legal-argument-while-pretending-to-support-musks/>

Twitter & ‘Stack:

Julia Ioffe: “Russia Is Where Occam’s Razor Goes to Die”: ‘I am not normally a false flag kind of girl, but Russia is a false flag kind of place and Putin is a false flag kind of guy. After all, it’s partly how he consolidated power…

Coffeemancer Vanvidum: ‘I prefer to believe that Clark is just as big as the perspective and cropping suggests…

Josh Barro: Jay Powell Brings the Pain: ‘The rate hikes will continue until well after the data improves…

Brian Potter: Why Are There So Few Economies of Scale in Construction?: ‘Making a building seven times as large only drops the cost per square foot by just under 20%…

Mary L. Trump: Brilliant Piece by Dahia Lithwick: ‘"[A]nyone who tells you not to prosecute . . . or investigate Trump because you will anger his supporters is delusional. His supporters are already extremely angry. We don’t negotiate with toddlers or terrorists”…

Commenting on a previous post I tried to argue that other economic hinges would have seemed just as transformational as 1870 to those who lived near them - whether for good or ill - and I was struggling to figure out whether it's tempting to think of 1870 as the biggest deal because it's closer. You've won me over that far - I'm still inclined to think that *all human history is hinge*, but you've convinced me that the acceleration of economic growth above the population level (a) happened in/around 1870 and (b) was a profound shift in the fundamentals of being human.

Still not down with it being the truest hing in human history, because while is may have been the hinge that made the most difference to the lived experience of the most people (so far), I can think of another axis for hinges which have been or may one day be equally transformational. That is, information sharing/mental alignment/the increasing complexity of communications by which we become the anthology intelligence that is humanity. Possible hinges: the invention of language, the printing press, the world wide web (near-instantaneous transmission of thought), in the direct brain-to-brain transfer (if that is ever more popular than the current near-instantaneous version of the web which at least allows for some illusion of individual control).

Re #25 Is it the flummoxed-ness that seems to have put an end (?) to the extraordinary growth 1870-2010?