Understanding Why so Many, Many False Starts in Sub-Saharan Africa...

An unsuccessful piece, in which I largely fail in my attempt to meditate on what might possibly be done to create a better future for Cameroon...

An unsuccessful piece, in which I largely fail in my attempt to meditate on what might possibly be done to create a better future for Cameroon...

Is there a path to some future process that could change Cameroon’s government to one like Denmark’s—or even just Singapore’s? And so produce not only the blessings of liberty but the accompanying prosperity of modern economic growth?

The ninety year-old President Paul Barthélemy Biya'a bi Mvondo has been in power since 1975, and was back in 2006 named—along with three other sub-Saharan African rulers—one of the world’s twenty worst living dictators by David Wallechinsky:

Timothy Burke: The News: Starting From Scratch: ‘Two Swarthmore students organized… “Africa Is Rising”…. [One of] the… speakers… really got my attention: Kah Walla, a Cameroonian… insisted that Cameroonians needed to imagine, plan for and even count on a political transition from the malfunctioning political order that was imposed on Cameroon during decolonization to a responsive and consultative state and a political system that serves its people rather than victimizes them…. Preparation, as Walla saw it, should include some form of ground-level conversation between Cameroonians in their home communities about what exactly they want from government, about what they think politics ought to be like….

Political visionaries… are driven nearly mad by the dysfunctionality of the states they endure. They can see designs which plainly should be better, and which in many cases, actually exist…. You do not have to pine for a millennarian vision…. You can just wish for social democratic administrative and institutional norms on the model of the Scandinavian states… or, to be honest, you could just wish for an authoritarianism that actually works on the model of Singapore…. [But] even… that more modest imagination of a re-imagined state… may have little to do with what most people in a given territory think about politics, authority, or government. That might be why those states work fairly well in Scandinavian nations: because they align with how the population by and large thinks about government and politics.

I think Kah Walla is right that the only way to build states that not only function but endure in sub-Saharan Africa is to start from scratch… with… a foundational conversation that rises up from all the people in all their communities…. [But] as long as the process is expected to culminate in something like a recognizable government in command of an internationally-agreed-upon territory that performs all the expected functions and behaves in all the expected ways, the conversation is never going to be more than a short speed bump in a circular road that leads back to the usual suspects…

In some ways, it is an old dream: to replace government as political domination over persons with government as the simple ancillary administration of things and the win-win coördination of processes of production: <https://www.google.com/search?hl=en&ie=8859-1&oe=8859-1&as_occt=body&num=25&sitesearch=www.marxists.org%2F&as_epq=%22government+of+men%22&as_oq=&as_q=&as_eq=&as_occt=all&btnG=Google+Search%21#ip=1>:

We see this in Friedrich Engels:

Friedrich Engels: Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution in Science: ‘When at last [the state] becomes the real representative of the whole of society, it renders itself unnecessary…. Tthere is no longer any social class to be held in subjection… and a special repressive force, a state, is no longer necessary…. The government of persons is replaced by the administration of things, and by the coördination of processes of production. The state is not “abolished”. It withers away… <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/anti-duhring/ch24.htm>

Or, alternatively:

Friedrich Engels: The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State: ‘The society which organizes production anew on the basis of free and equal association of the producers will put the whole state machinery where it will then belong—into the museum of antiquities, next to the spinning wheel and the bronze axe…

But it is older. Engels attributed its origin to St. Simon in his Letters from Geneva:

Friedrich Engels: Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science: ‘What is here already [in 1802] very plainly expressed is the idea of the future conversion of political rule over men into an administration of things and a direction of processes of production…

Engels’s and St.-Simon’s dream has by-and-large been accomplished in Denmark, and, in a different way, perhaps it has been accomplished in Singapore, perhaps.

But clearly not in Cameroon.

Why not? And is there any way that things could possibly be changed? And is Kah Walla right in how to start changing them?

The major purpose of the governments of Denmark and Singapore is not to be domination-and-exploitation gangs extracting resources from society by force and fraud so that the members of the gang and their families can have what they regard as enough. The major purpose of the government of Denmark is one of administering things and coördinating production processes, provisioning public goods; maintaining a property and ownership and social power order largely regarded as legitimate—and thus a foundation for win-win coöperative production and living—against threats from roving bandits, local notables, and the government’s own functionaries; providing social insurance; and keeping a weather eye on the evolving distribution of property to maintain a degree of fundamental equality of status. The government of Denmark is kept on course by the fact that if it fails to accomplish these tasks in the judgment of the electorate, the electorate will vote the bastards out—and the police and the military and, perhaps, NATO will if necessary enforce the judgment of the electorate.

And the government of Singapore? It too appears, largely, to be one of administering things and coördinating production processes, provisioning public goods; maintaining a property and ownership order largely regarded as legitimate—and thus a foundation for win-win coöperative production and living—against threats from roving bandits, local notables, and the government’s own functionaries; providing social insurance; and keeping a weather eye on the evolving distribution of property to maintain a degree of fundamental equality of status. But the government of Singapore is kept on course by the fear of the humiliation of its members in the eyes of themselves and their predecessors should it fail to do so, and by a keen-eyed realization that Singapore’s prosperity could exit very rapidly indeed to Melbourne, Sydney, and Taipei should they fail to administer things and coördinate production processes.

But the government of Cameroon is different. The point is not to maintain a property and ownership order largely regarded as legitimate against threats from the government’s own functionaries—the point is to revise the property and ownership order in favor of the government’s own functionaries. And the provisioning of public goods? The provision of social insurance? The moderating of neoliberal and other processes magnifying income and wealth inequality? Should such things happen as a byproduct of the government’s own functionaries reörienting the property and ownership order of Cameroon into a configuration more to their and their families’ liking, well and good. But if not? Shrug.

One does wonder about the 23 year-old Paul Biya back in 1956, newly graduated at the age of 23 from the Lycée Général Leclerc Yaoundé with a Bacc. in Philosophy. He then set off to Paris for six years of higher education: at Lycée Louis Le Grand, the Université Paris Sorbonne (Faculty of Law), the Institut d'Études Politiques, and the Institut des Hautes Études d'Outre Mer.

Did he have any idea that nearly seventy years later he (and Cameroon) would be where and what they are today?

What did Paul Biya learn being trained as a lawyer in Paris in France between 1956 and 1962?

Those were the years in which the anticolonialist UPC was outlawed by the French colonial rulers, and launched its guerrilla war. It was opposed by the French colonial army—most soldiers born in Cameroon but some in France, many French-born officers, and a French-born chief of staff The French government responded by granting Cameroon internal autonomy in 1957 under André-Marie Mbida, and independence on January 1, 1960 under Ahmadou Ahidjo. The UPC’s president, Felix Moumié, was poisoned in Geneva in October 1960 by the French SDECE. The UPC’s Secretary General, Ruben Um Nyobé, had been killed by the French army near the village of Boumnyebel where he was born. (One of the UPC’s two Vice Presidents, Abel Kingue, died in a Cairo hospital in 1964 after having been imprisoned by the Ghanian government of Kwame Nkrumah, and upon release suffering from severe hypertension and “behavioral problems”; the other Vice President, Ernest Ouandié, continued to lead the UPC’s guerrillas until he was captured by French and Cameroon soldiers in 1970 and executed.)

President Ahmadou Ahidjo had proven himself very good at winning elections administerd by the French colonial administration from among a pool of candidates the French allowed to run. The French installed him as President Ahmadou Ahidjo of independent Cameroon in 1960. But a year after independence, in 1961, Adhijo began calling for a one-party state. By 1965 Adhijo was head of the only political party, the CNU, and his approval was required for all nominations for seats in the National Assembly.

And in 1962 Paul Biya had returned to Cameroon at the age of 29 to a job as a Chargé de Mission at the Presidency—a special assistant to President Ahidjo.

When Paul Biya returned to Cameroon, did he look forward to a career as a bureaucrat-technocrat, serving politicians who could win majorities at the ballot box via some combination of public charisma, private network persuasion, and party organization? Did he see his job as likely to be one of the administration of things, and the win-win coördination of productive processes? Or did he think that at the age of ninety he would be a (relatively mild) tyrant at the top of a parasitic resource-extraction military-backed bureaucracy that kept there from being enough for the citizens of Cameroon in general by taking so that there could be enough for the bureaucracy and their families?

Starting in 1962 Paul Biya served Ahmadou Ahidjo well, for a while. In 1975 the Muslim Ahidjo named the Christian Biya Prime Minister. Ahidjo resigned the presidency—he retained his post as head of the CNU—for “health reasons” in 1982. Biya then became president of Cameroon. But by July 1983 Ahidjo was in exile in France. By August 1983 Biya had “discovered” that Ahidjo was plotting to overthrow him. By February 1984 Biya sentenced Ahidjo to death in absentia for the plot. In April 1984 Biya ordered the removal and transfer of all presidential palace guards from the Muslim north of Cameroon. And in the next several days somewhere between 71 and 1000 people died in fighting before pro-Biya forces attained secure control.

Adhidjo died in Senegal in 1989.

Step back: It is not just a story about Cameroon, and a young France-educated lawyer becoming a corrupt and corrupting dictator.

When the European colonial powers withdrew from formal control over their Sub-Saharan African empires, the bureaucracies and structures of government left behind were that of the industrial west: representative parliamentary institutions, independent judiciaries, laws establishing freedom of speech and of assembly, and a strong civil service tradition among the bureaucracy. The hope was that, freed from the oppressive controlling hand of colonial rule, democracy in the newly-independent former colonies was thought likely to flourish. And since their economies would no longer be controlled in the interests of the imperial power, economic prosperity should follow as well.

But it was not to be.

By and large the colonial powers had been profoundly uninterested in creating the kind of economic base on top of which governance could become the administration of things and the win-win coördination of productive processes. Economic historian Robert Allen had a checklist that countries needed to work through in order to step onto the escalator to prosperity that was post-1870 economic growth:

a stable, market-promoting government;

building railroads, canals, and ports;

chartering banks for commerce and investment;

establishing systems of mass education;

imposing the right kind of tariffs to protect the growth of the industries and the communities of engineering practice that support them, and in which long-run comparative advantage and prosperity lay; plus

a “Big Push” to set all the virtuous circles of economic development in motion.

Those were simply not things that colonial masters were concerned about.

But, even so, in most of Sub-Saharan Africa the political aftermath of decolonization turned out to be a long-run disappointment. Westminster-style parliamentary politics and independent judiciaries soon became very rare exceptions. Instead, regimes emerged that derived their authority not from electoral competition between different groups of possible representatives but from the army and the police suppressing dissent with a varying level of brutality, or—in the best case—from populist attachment to a charismatic nation-symbolizing reforming leader.

The speed with which political democracy collapsed throughout much of the newly-decolonized third world was staggering. It suggested that the institutions and practices that keep representative political democracy functioning throughout so much of the industrial core are fragile and vulnerable.

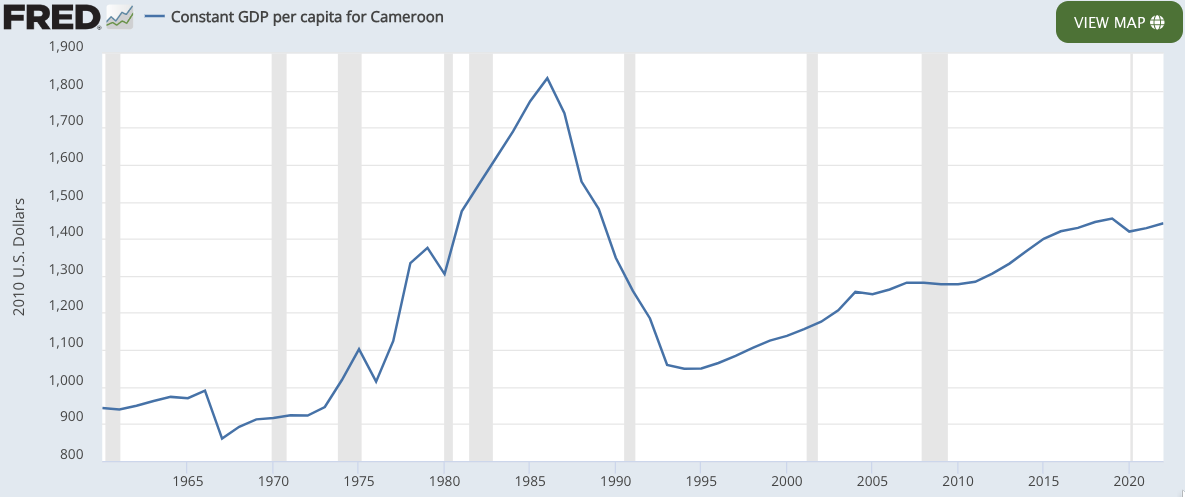

And in many places the economic aftermath was also a near-catastrophe. In Africa south of the Sahara, as of 1995 only Botswana, Lesotho, the Cameroon—yes, Paul Biya’s corrupt government was far from the worst—and perhaps one or two others managed to reduce the relative income gap vis-a-vis the industrial west before the coming of post-1995 African economic growth. Kenya, Mali, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Guinea, the Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, and South Africa among others in Africa have seen rising living standards, but a rising relative income gap vis-a-vis the industrial core. Perhaps in these countries the glass was still half-full: increasing relative income gaps vis-a-vis the industrial core have been nevertheless accompanied by rising living standards and productivity levels. But, as of the end of the post-colonial generation in 1995, Mozambique, Togo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Senegal, Ghana, Madagascar, Chad, Zaire, Zambia, Niger, and Uganda, among others?

As Robert Bates wrote at the end of the 1970s: “Palm oil in Nigeria, groundnuts in Senegal, cotton in Uganda, and cocoa in Ghana were one among the most prosperous industries in Africa. But in recent years, farmers of these crops have produced less, exported less, and earned less…” Africa south of the Sahara faced the paradox that the only continent in which farmers still perhaps made up a plurality of the workforce was spending an ever-increasing portion of its export earnings on imported food.

Why did this happen? What went wrong? The storehouse of industrial technologies developed since the industrial revolution is open to all. The forms of knowledge and technologies that make the industrial west today so rich are public goods. The benefits from tapping this storehouse are enormous, and have the potential to multiply the wealth of all social groups and classes—property owners and non-property owners, politically powerful and politically powerless alike—manyfold. All developing economies ought to have experienced not just substantial growth in absolute living standards and productivity levels, but ought to have closed some of the relative gap vis-a-vis the world’s industrial leaders since independence. Yet a large proportion of the successor régimes to colonial domination have failed to do so.

Absolute poverty is not the reason. Even relatively poor parts of the third world today have levels of material wealth as high as those found in seventeenth century Scotland or Italy. Resource scarcity is not the reason: the world as a whole can far more than feed itself, and there is no shortage of mineral and energy resources to provide constructive and socially valuable work for even unskilled hands. One short and too-simple answer is that the fault—where there is fault—lies in governments: kleptocracy—govenment by the thieves, as it has been named in analogy with aristocracy (goverment by the best), monarchy (goverment by the one), and democracy (government by the people)—has impoverished much of the third world over the past generation.

Yet in a historical perspective kleptocracy—rule by the thieves—is nothing new. Perhaps the major drawback to the invention of agriculture was that you had to be around to harvest the fields that you had planted. This meant that you could not run away when thugs-with-spears came by to demand the lion’s share of your crops. And as this became generally known, people got into the business of supplying spears for the thugs: we call such people “kings.” Most governments at most times in most places have followed policies that show little interest in nurturing sustained increases in productivity. Why should we expect the modern Third World to be any different? We would expect that governments would take great care to prevent food riots in the capital (and they do), and would follow the advice of the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus and keep the army well-fed, well-paid, and equipped with lots of new weapons to play with (and they do). But the lifespan of the average government is too short to expect it to take a serious interest in the project of long-run economic development. This is the short answer.

But it is insufficient. Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa since independence has been notably bad in world-historical context. Why do bureaucrats, army officers, and politicians there, as benevolent and as concerned with national wealth as bureaucrats, army officers, and politicians anywhere, so often sacrific economic development and the long-run interests of all to the short-run interests of a relative few?

As I wrote in my Slouching Towards Utopia <http://bit.ly/3pP3Krk>:

The first priority of governments must be to prevent food riots in the capital. Régimes rule peacefully in part because they control the visible centers of sovereignty: those buildings in the capital from which members of the bureaucracy expect to receive their orders, and the centrally located radio and television broadcast sites through which rulers speak to their nations. If an urban riot overruns the president’s palace, the ministries, or the television stations, the government’s rule is in serious danger. Conversely, bread, circuses, and a well-supplied and compliant police force keep riots at bay.

The second priority of governments is to keep the army well fed, well paid, and equipped with lots of new weapons to play with. Rulers can only rule so long as the army tolerates them.

The third priority is to keep the bureaucrats and the political operatives content, and any potential opposition quiet or disorganized.

For insecure rulers, pursuing these aims almost always takes precedence over policy. All rulers believe they are the best people for the job. Their rivals are at best incompetent, most likely wrongheaded and corrupt, and at worst amoral and destructive. As these insecure rulers see it, nothing good will be achieved for the country or the people unless they maintain their grip on power. Only after the government’s seat is secure will debates about development policy take place. But the pursuit of a secure hold on power almost always takes up all the rulers’ time, energy, and resources. The life-span of the average government is often too short for any reasonable historian-critic to expect it to focus on long-run economic development.

And, as Niccolò Machiavelli wrote in his little book about new princes back in the early 1500s, things are even worse with a new regime, in which the first task is currying supporters, who are unlikely to remain supporters unless they benefit.10 So, job number one in building a state is to seize control of and redirect benefits, tangible and otherwise, to the most influential of one’s supporters. And that process of seizure and redirection follows a different logic—a very different logic—than that of channeling resources to produce rapid economic growth.

Most rulers would be benevolent and strongly pro-development if they thought they could be. Paul Biya would have been very happy to preside over a Cameroon that grew as fast as South Korea. But believing that you can be benevolent—rather than tolerating growth-destroying corruption because you need to keep those in the army, the police, and the bureaucracy who might unseat you in the next five years happy—requires stability and se- curity, and increasing prosperity can be a powerful source of increased stability and security.

But why don’t potential entrepreneurs—those who would benefit most from pro-development policies, and whose enterprises would in turn benefit many others—work to overthrow an anti-development ruling regime? Political scientist Robert Bates asked this question of a cocoa farmer in Ghana. Bates was seeking to learn why farmers did not agitate for a reduction in the huge gap between the (very low) price the government paid them for cocoa and the (higher) price at which the government sold the cocoa on the world market. The farmer “went to his strongbox,” Bates reported, “and produced a packet of documents: licenses for his vehicles, import permits for spare parts, titles to his real property and improvements, and the articles of incorporation that exempted him from a major portion of his income taxes. ‘If I tried to organize resistance to the government’s policies on farm prices,’ he said while exhibiting these documents, ‘I would be called an enemy of the state, and would lose all these.’”

This isn’t always or only an accident of “overregulation.” From an economic development perspective, potential future entrants into industries produce the most social benefit. Yet because they have no existing businesses or clients, they also have no re- sources with which to lobby the influential. Therefore, from the perspective of those in power who wish to remain so, restricting future entrants into industries is a way of doing existing busi- nesses a favor at a very low political cost. Since the overvalued exchange rate has made foreign currency a scarce good, competition from manufacturers abroad can also be easily strangled in select sectors as a favor to key existing businesses….

Strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto prosperity in the global south. The “who?” question has a more straightforward answer: the global north, collectively, had the wealth and power to take steps to arrange things more favorably for the global south, and it did not do so. Successful economic development depends on a strong but limited government. Strong in the sense that its judgments of property rights are obeyed, that its functionaries obey instructions from the center, and that the infrastructure it pays for is built. And limited in the sense that it can do relatively little to help or hurt individual enterprises, and that political power does not become the only effective road to wealth and status…

To achieve the primary aim of damping down potential threats to the government, money is necessary. And not just any kind of money:

urban workers who might riot and seize the presidential palacecan be appeased by cheap food and high wages,

but the army and the bureaucracy require imported luxuries,

that requires that the government gain control of exports—and squeeze export agriculture most of all;

squeezing the rest of agriculture next: cheap food helps to avoid urban riots; and

an overvalued currency makes everyone willing to do the government favors so that they can have access to scarce currency-import permits; plus

it makes imported luxuries relatively cheap.

The only potentially politically powerful groups that remain whose interests are harmed by these policies are the bourgeoisie, the business class, the entrepreneurs and industrialists.

But those are the guys who could and do serve as the engine of economic development in market economies.

Making things worse, throughout the post-World War II period intellectuals on pretty much all sides have applauded the strength of the state, on the ground that only a strong state could perform the historical tasks necessary for economic development. As one usually clear-eyed observer, the political scientist John Hall, put it, very wrongly:

forced development is socially brutal. Such development cannot be achieved under the ægis of soft political rule, and this means that the chances of a transition to democracy are correspondingly at a discount. [M]odernization, under whatever politicial ægis, involves at least disciplining the peasantry and at most forcibly removing it from the land. the removel of tribalism, the destruction of rival cultures, the creation of a lingua franca, and the establishment of national bureaucracies. Third World countries have learnt with time that successful modernization is impeded by democracy. For people do not easily accept the loss of their land and of their customary ways of life: this requires force [and] a totalizing ideology…

When you look at the successful economic developers of either the nineteenth or thet twentieth centuries, you can see that this is nonsense. Successful development does not require “disciplining the peasantry” or “forcibly removing it from the land.” Successful development requires luring the peasantry off the land to higher-wage higher-productivity factory and commercial jobs in the growing cities. The prevalence of the belief that modernization “under whatever political aegis” is socially brutal rejects as a model for development the experience of the United States, France, Italy, Belgium, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and others and accepts as a model for development the Soviet Union of the 1930s: Stalin.

The best that can be said of this is that it is fuzzy thinking.

But it is fuzzy thinking that has made a—disastrous—difference. What is wanted to support successful economic development is a government more like that of eighteenth and nineteenth century Britain and America: a government that is strong but limited: strong in the sense that its judgments of property rights are obeyed, that its functionaries obey instructions from the center, and that the infrastructure it pays for is built, limited in the sense that it can do relatively little to help or hurt individual enterprises and that political power is not the only effective road to wealth and status. Yet attempts at “statebuilding” since the middle of World War II have often aimed at a state that is strong and not limited—and have usually wound up with a state that is weak but unlimited: political power is the only effective road to wealth, but functionaries ignore instructions and extort bribes for administrative favors and the infrastructure that it pays for is not built.

But do note that in all of this story I have told above, there is next to nothing about Sub-Saharan Africa. What makes Sub-Saharan Africa especially bad in this context. Again, my take from Slouching Towards Utopia:

In 1950, more than half the world’s population still lived in extreme poverty: at the living standard of our typical pre-industrial ancestors. By 1990 it was down to a quarter. By 2010 it would be less than 12 percent. And in 1950, most of this ex- treme poverty was spread throughout the global south. Thereafter it would become concentrated in Africa, where, by 2010, some three-fifths of the world’s extreme poor would reside.

This concentration came as a surprise: there had been few signs back in the late colonial days of palm oil, groundnuts, cotton, and cocoa exports—the days when Zambia was more industrialized than, and almost as rich as, Portugal—that Africa south of the Sahara would fall further and further behind, and not just be- hind the global north, but behind the rest of the global south as well. From 1950 to 2000, Egypt and the other countries of North Africa grew along with the world at about 2 percent per year in average incomes. But—to pick three countries from south of the Sahara—Ethiopia, Ghana, and Zambia grew at only 0.3 percent per year.

Thinkers like Nathan Nunn grappled with this data and concluded that this retardation had something to do with the massive slave trades that had afflicted Africa in previous years.

There had been other massive slave trades: the armies and elite citizens of classical Greek and Rome had stolen perhaps 30 million people over the span of a millennium and moved them around theMediterranean. The Vikings had stolen perhaps 1 million—equal opportunity catchers and movers of slaves from Russia to western Europe or down to the Aegean, and moving Irish and Britons to Russia. Over the millennium before 1800, perhaps 1.5 million Europeans were kidnapped and taken as slaves to North Africa. Between 1400 and 1800, some 3 million people were enslaved in what is now southern Russia and Ukraine and sold south of the Black Sea.

But the African slave trades were bigger than almost all others: perhaps 13 million were carried across the Atlantic over the period from 1600 to 1850; 5 million were carried across the Indian Ocean between 1000 and 1900; 3 million were carried north across the Sahara from 1200 to 1900, and an unknown number were taken in internal African slave trades—which did not stop when the transoceanic trades did: even if Europeans and Middle Easterners would no longer buy slaves, the slaves could be put to work on plantations producing crops that they would buy.

Compare these numbers to a population in Africa in 1700 of perhaps 60 million, and to perhaps 360 million people born in Africa and surviving to age five over the years from 1500 to 1800.

And being subjected to millennium-spanning slave raiding as a major part of life could well create a long-lasting durable culture of social distrust.

In a well-functioning market economy you begin nearly every meeting you have with a stranger thinking that this person might become a counterpart in some form of win-win economic, social, or cultural exchange. This is not the case if you think there is even a small chance that the stranger is in fact a scout for people with weapons over the next hill who will seek to enslave you, and perhaps kill you or your family in the process. This background assumption of distrust did not matter much as long as the trading and commercial infrastructure of the colo- nizers governed economic activity. But after the colonizers left, the distrust came to the forefront, and it led people to grab for weapons more quickly and more often than they would have in a more trusting society….

Nigerian prime minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa… had been born in the north of the British colony of Nigeria in 1912 and had been sent to boarding school at Katsina College. There, he was student number 145, to be slotted into the imperial bureaucracy as a teacher of English. He did very well. By 1941 he was a headmaster. In 1944 he was sent to University College London, to be trained to become a schools inspector for the colonial administration.

But earlier, back when he was twenty-two, in 1934, a colonial official named Rupert East had commissioned five novellas, to be written in Hausa, in an attempt to spread literacy. East had wanted to build up an “indigenous literature” that was more or less secular—that would not be “purely religious or written with a strong religious motive.” Abubakar Tafawa Balewa contributed, and he chose to write about slavery.

In his short novel Shaihu Umar (Elder Umar), the protagonist’s students distract him from teaching them the Quran by asking him how he came to be a teacher. The story that follows is of his enslavement and its consequences: large-scale slave raids, kidnappings, adoptions by childless slavers, and more kidnap- pings. The protagonist finally meets up with his mother (she has been kidnapped and enslaved too, by the guards she had hired) in Tripoli. She sees that he is pious and prosperous, and then she promptly dies. The vibe is[, as Aaron Bady put it,] that “people really will do terrible things for [not very much] money” and that “the world is a Hobbesian war of all against all, but if you read the Quran really well, then you’ll prob- ably prosper, maybe.”

Balewa used his post as a traveling schools inspector to enter politics in Nigeria in the 1940s. He was one of the founders of the Northern People’s Congress. By 1952 he was colonial Nigeria’s minister of works. By 1957 he was prime minister. In 1960 he became prime minister of an independent and sovereign Nigeria. He was reelected in 1964. And then in January 1966 he was murdered in the military coup led by the Young Majors—Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu and company—whose troops slaughtered senior politicians and their generals and their wives, and then were themselves suppressed by a countercoup led by army commander Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi.

Aguiyi-Ironsi was assassinated six months later in a July counter-countercoup led by Yakuba Gowon. A year later the Igbo people declared the independent republic of Biafra, which was suppressed after a three-year war causing some 4 million deaths (out of a population of about 55 million), the overwhelming ma- jority of them Igbo dead of starvation. Yakuba Gowon was over- thrown by Murtala Muhammed in July 1975. And Murtala was then assassinated in February 1976. A return to civilian rule in 1979 lasted only until 1983, when the next military coup took place in Nigeria…

You may have noted that I have wondered very far from Cameroonian activist-politician Kah Walla’s hopes to plant the seeds of political transition by starting with “some form of ground-level conversation between Cameroonians in their home communities about what exactly they want from government, about what they think politics ought to be like… [as an alternative to the] dysfunctionality of the states they endure…”

But I think that Kah Walla is right. Somehow the people of Cameroon have to begin to regard the proper role of the state as a thing that is a steward responsible for maintaining and supporting society’s generally accepted order of property and social power, rather than its master extracting resources from those not lucky enough to have gained the approval of Paul Biya, or his lieutenants, or his sub-lieutenants. But to do that the people of Cameroon need not to think of themselves as individuals, or members of families (one of the members of which might get a government job with income opportunities), or even clans. They need to think of themselves as citizens: people all similarly situated and thus all having similar expectations and demands of what the government needs to do in order to gain their consent and hence derive any just powers at all. And out of that there needs to come a societal near-consensus that if a government that does not have just powers “it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness…”

And in order to do that, the people of Cameroon need to start by talking to each other. Committees of Correspondence worked once. Some analog might work again.

God knows there are few enough other options.

References:

Balewa, Abubakar Tafawa. 1934 [1989]. Shaihu Umar, Princeton, NJ: Markus Weiner Publishers.

Bady, Aaron. 2021. “This book is about seventy pages long…” Twitter. May 9. <https://twitter.com/zunguzungu/status/1391478457134030849>

Bates, Robert. 1981. Markets and States in Tropical Africa: The Political Basis of Agricultural Policies. Berkeley: University of California Press. <https://archive.org/details/marketsstatesint00bate>.

Bates, Robert. 2008. When Things Fell Apart: State Failure in Late-Century Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press. <https://archive.org/details/whenthingsfellap00bate>.

Burke, Timothy. 2024. “The News: Starting From Scratch”. Eight by Seven. February 14. <http://timothyburke.com/p/the-news-starting-from-scratch>.

Camer.be. 2010. “Remembering Abel Kingue”. <https://web-archive-org.translate.goog/web/20100418064938/http://www.camer.be/index1.php?art=9740&rub=6:1&_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp>.

Comte, Auguste. 1822. Plan des travaux scientifiques nécessaires pour réorganiser la société. Paris: Aubier-Montaigne. <https://openlibrary.org/books/OL22183703M/Plan_des_travaux_scientifiques_n%C3%A9cessaires_pour_r%C3%A9organiser_la_soci%C3%A9t%C3%A9>.

Congress of the North American Colonies. 1776. Declaration of Independence. Philadelphia: John Dunlap. <https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/declaration-of-independence/>.

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2023. Slouching Towards Utopia: The Ecconomic History of the Twentieth Century. New York: Basic Books. <http://bit.ly/3pP3Krk>.

Engels, Friedrich. 1877. Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science. Leipzig. <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/anti-duhring/index.htm>.

Engels, Friedrich. 1884. The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State. Hottingen-Zürich. <https://archive.org/details/originoffamilypr0000enge>.

Google. 2024. “Search: ‘“government of men” site:www.marxists.org/’. <https://www.google.com/search?hl=en&ie=8859-1&oe=8859-1&as_occt=body&num=25&sitesearch=www.marxists.org%2F&as_epq=%22government+of+men%22&as_oq=&as_q=&as_eq=&as_occt=all&btnG=Google+Search%21#ip=1>.

Hall, John A. 1986. Powers and Liberties: The Causes and Consequences of the Rise of the West. Berkeley: University of California Press.

<https://openlibrary.org/books/OL2550647M/Powers_and_liberties>.

Kafka, Ben. 2012. “The Administration of Things: A Genealogy”. W. 86th, May 21. <https://www.west86th.bgc.bard.edu/articles/the-administration-of-things-a-genealogy/>.

de St.-Simon, Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte. 1802. Letters from Geneva. <https://archive.org/details/politicalthought0000sain>.

Wallechinsky, David. 2006. Tyrants: The World's 20 Worst Living Dictators. New York: Regan Books. <https://archive.org/details/tyrantsworlds20w00wall>.

I have found Quentin Skinner's work on what he calls Neo Roman Republicanism helpful. The state is the people and the government is empowered by the people. The West has embraced this notion. I find it more insightful than Marxist commentary and less alienating.

Another helpful perspective I frequently return to is Joseph Henrich and The W.E.I.R.D.est people on earth. A relevant component that seems to be missing in sub-Saharan Africa is 'prosocial trust', do we trust our a stranger and importantly our government to act as they say they will and that laws and culture say they will. Think of getting a fair shake in the courts or what it took to create the extremely high liquidity of our financial markets and its foundations which most of us never need to know about.

It is also an unfortunate historical fact that independence was granted at a time when ideas of government planning/direction of the economy was in the ascendent. I daresay that Paul in Paris did not learn "Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice; all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things."