Were We Expelled from Egalitarian Eden Not by the Pomegranate, But by the Plough and the Ox? Perhaps...

Portable tools, farmstead implements, domesticated animals, serfdom, & slavery—with increased civilizational complexity the dimension of the space of potential inequalities increases, & do we need mor

Portable tools, farmstead implements, domesticated animals, serfdom, & slavery—with increased civilizational complexity the dimension of the space of potential inequalities increases, & do we need more than that to account for our expulsion from Gatherer-Hunter Age egalitarian Eden?…

A very nice brand-new paper from Sam Bowles and Mattia Fochesato tracing oru expulsion from Gatherer-Hunter Age egalitarian Eden to—no surprise—the state and slave-raiding war and also—here is the innovation—plausibly to the ox and the plough:

Bowles, Samuel, & Mattia Fochesato. Forthcoming 2024. “The Origins of Enduring Economic Inequality”. Journal of Economic Literature. <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.20241718>.

(But where is their coäuthor Amy Bogaard?)

What do I say? I say perhaps.

Perhaps there is some complicated story about the ox and the plough leading to a great reduction in the extent to which land is subject to decreasing returns, and hence to the the erosion of the “culture of aggressive egalitarianism [that] may have thwarted the emergence of enduring wealth inequality until the Late Neolithic when new farming technologies raised the value of material wealth relative to labor…”

But, as always in these literatures, we run headlong into the first-order problem of prehistoric sociobiology and biosociology: claims are almost always just-so stories by which people project what they think of the present onto a distant past, of which we know very, very little, and assert much more strongly than they should that things must have been that way long ago.

I would seize the high ground of the null hypothesis, and ask Bowles and Fochesato to work harder to push me off of it. I would say that we have, here, five dimensions of acquisition and accumulation: tools you can carry, tools and implements at your farmstead, animals, the serfdom that is coërcion of farmers within reach, and slavery.

Is there much more going on here than simply an expansion of the dimensionality of the space of possible wealth inequality, and so we get more of it?

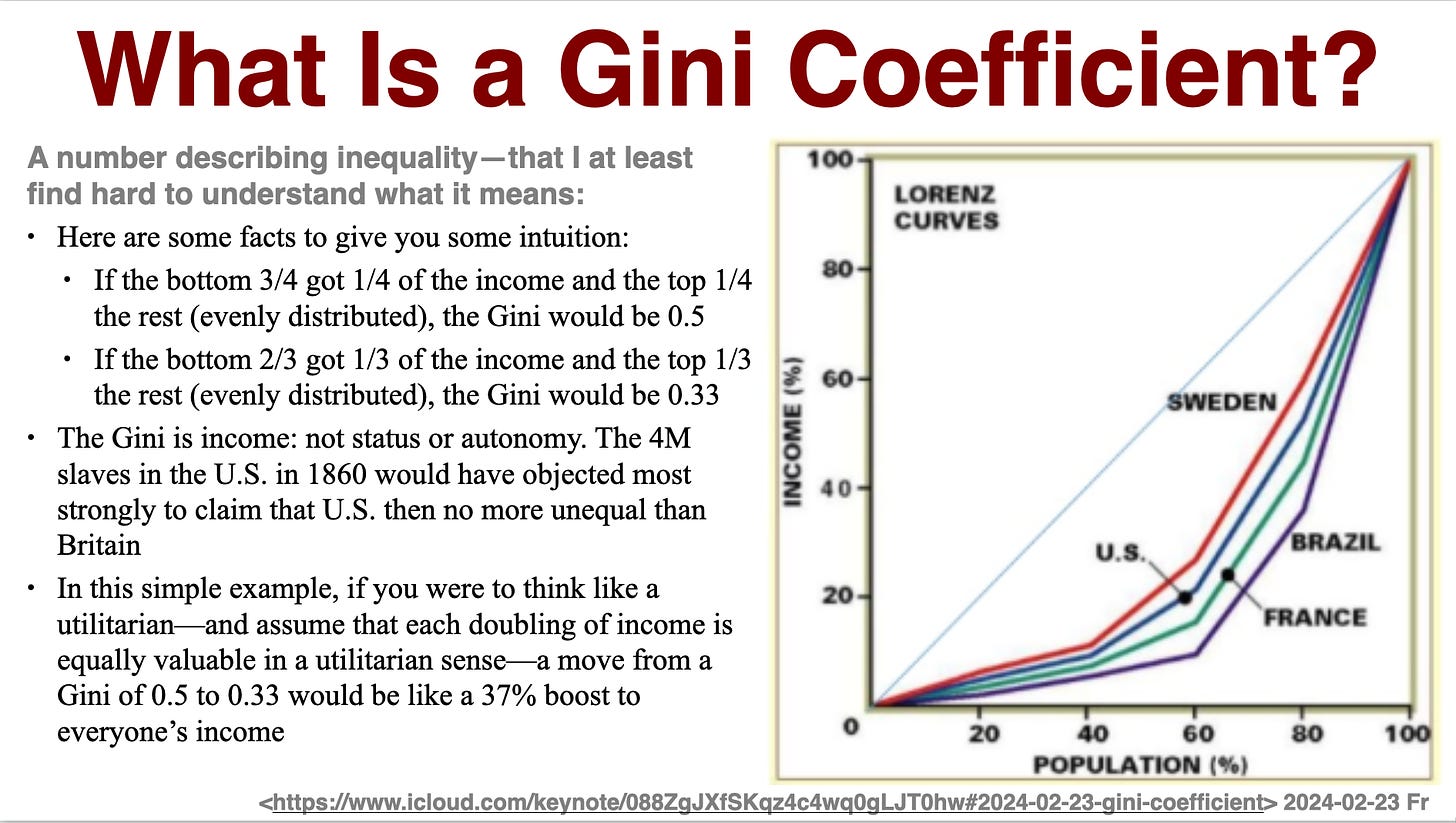

And may I say that whenever I have to think of Gini coefficients, I get hives?

Along a better disentangled branch of the multiversal world quantum state than this one, Corrado Gini <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corrado_Gini> would never have been born, and the Gini coefficient would simply not be a thing. It is an extremely non-intuitive measure of inequality. The lifebouy I try to cling to is this:

If the bottom 3/4 held 1/4 of the wealth and the top 1/4 the rest (evenly distributed), the Gini would be 0.5.

If the bottom 2/3 held 1/3 of the wealth and the top 1/3 the rest (evenly distributed), the Gini would be 0.33.

In this simple example, if you were to think like a logarithmic-real-income utilitarian—and assume that each doubling of wealth is an equally valuable contribution to the social welfare function—counterfactually shifting from that Gini of 0.5 to that of 0.33 would have the same effect on social welfare as a 37% boost to everyone’s income.

The Gini is income or wealth only, not status or autonomy: The four million slaves in the U.S. in 1860 (out of a total thirty million population) would have objected most strongly to any claim that the U.S. was then no more “unequal: than Britain.

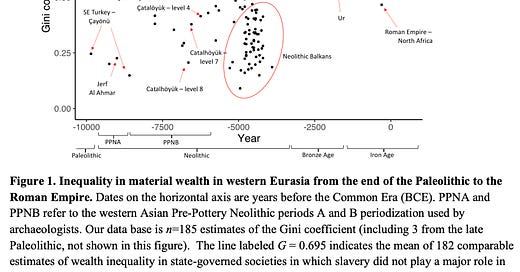

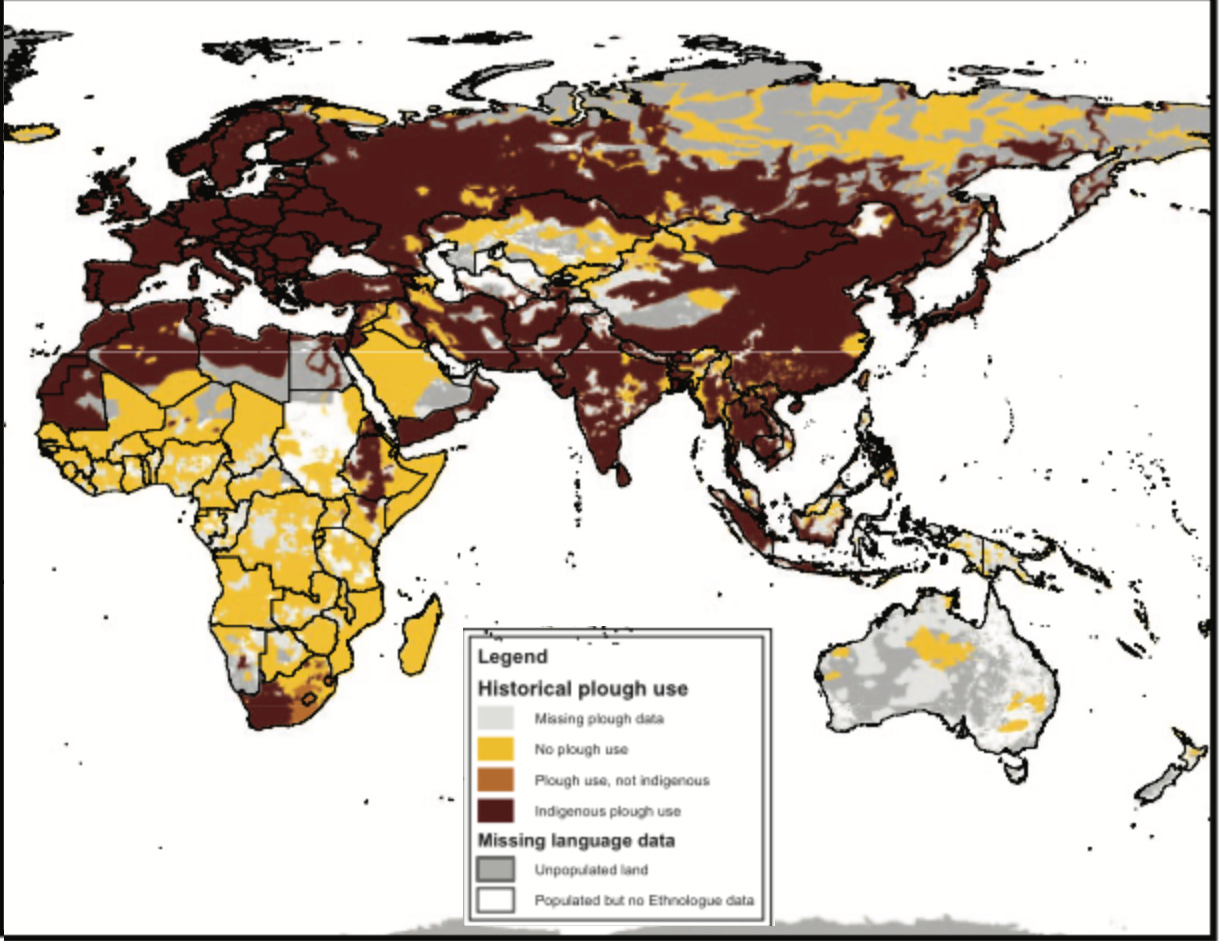

This is throat-clearing to help you understand a pre-Mediæval Agrarian-Age Western-Eurasia Gini-coefficient guess-figure—I will not call them “estimates”—constructed by Sam Bowles and Mattia Fochesato:

The G=0.695 “mean of 182 comparable estimates of wealth inequality in state-governed societies in which slavery did not play a major role in production for the period from 300 BCE to 2000” corresponds to that found in a two-class society in which the upper class is 15% of the population and holds 85% of the wealth—thus an upper-class member holds thirty times the wealth of a lower-class member.

The United States’s wealth Gini coefficient today is about 0.85. For a two-class society, such a Gini is found when 1/13 of the population holds 12/13 of the wealth: about the same as in the Roman Empire—an upper- to lower-class wealth ratio of 144. Ur of the Chaldees had a Gini of about 0.65: equal to that of 1/6 of the population holding 5/6 of the wealth—an upper- to lower-class wealth ratio of 25. And for the Neolithic Balkans, they averaged about 0.33: 1/3 of the population holding two-thirds of the wealth—an upper- to lower-class wealth ratio of 4.

Samuel Bowles & Mattia Fochesato: The Origins of Enduring Economic Inequality: ‘Archaeological evidence suggest[s]… that among hunter-gatherers and farmers in Neolithic western Eurasia (11,700 to 5,300 years ago) elevated levels of wealth inequality… were ephemeral and rare compared to the substantial enduring inequalities of the past five millennia…. we seek to understand… the processes by which substantial wealth differences could persist over long periods and why this occurred only… [more than] four millennia after the agricultural revolution…. A culture of aggressive egalitarianism may have thwarted the emergence of enduring wealth inequality until the Late Neolithic when new farming technologies raised the value of material wealth relative to labor and a concentration of elite power in early proto-states (and eventually the exploitation of enslaved labor) provided the political and economic conditions for heightened wealth inequalities to endure… <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.20241718>

Sam and Mattia’s hypothesis—I will not call it a conclusion—is that by-now established standby <https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt005>: the plough (and the domesticated ox). There were four factors that expelled us from egalitarian Eden:

First… sedentary living, along with harvesting and then cultivating storable cereals and eventually raising large animals, provided opportunities for private ownership of important and readily stored means of subsistence…. But these developments were not associated with enduring modern levels of wealth inequality, due to the persistence (albeit under duress) of “aggressively egalitarian” social norms and cultural practices.

Second… capital-intensive, labor-saving methods of production, particularly plow-based farming, raised the shadow price of land and other capital goods relative to labor… increased the value of forms of wealth—land and draft animals—that… could be very unequally held, were readily transmitted across generations and were subject to increasing returns and substantial shocks….

Third… the gradual centralization of the effective use of coercion… mitigated the likelihood of either internal or external challenges to the wealth holdings of the elite….

Fourth… enslavement… converted labor itself to a form of privately owned material wealth that could be very unequally held once sufficient coercive power had been concentrated in elite hands… both subject to shocks and transmitted over generations….

The second point above (based on joint work with Amy Bogaard) addresses… the [previous] lack of a convincing explanation as to how farming populations without marked wealth inequalities persisted through much of the Neolithic…. The key step, if we are right, was not the emergence of an agricultural surplus or an extractive elite with coercive powers but instead the introduction of the ox-drawn plow… which effectively increased the scarcity of land and the redundancy of labor, providing the conditions for the emergence of a subordinate working class… the result of both an increase in both intergenerational transmission of wealth, and (non-insured) wealth shocks….

We have documented a shift from what appear to have been cases of episodic and rare elevated levels of wealth inequality in the Late Paleolithic and Early Neolithic… to sustained high levels of wealth inequality in the Bronze and Iron Ages…. A closing conjecture. The increase in material wealth inequality associated with the transition from a labor-limited hoe-based farming to a land-limited plow agriculture might have also proved to be ephemeral had it not been for the Bronze-Age concentration of coercive power… [in] the emerging economic elite. The changes in both farming technology and political organization may have been jointly necessary and sufficient to explain the origin of enduring wealth inequality…

There are, of course, the obvious caveats.

First, this is wealth inequality in the form of personal chattels—not income inequality. Incomes are almost surely significantly more equalized than wealth. And social status—the power to command deference and action from others, and the personal psychological benefits that flow from positions of prestige, honor, and domination—may be more or less equalized than wealth.

Second, note that personal-chattel wealth typically takes three forms:

Things to make your life here-and-now more comfortable.

Grave goods to make your afterlife more comfortable.

Tools to make you more productive.

Advances in technology that multiply the possible forms and utility of productive capital—type (3)—are going to lead to increases in measured wealth inequality whether or not society is actually more unequal in consumption opportunities and status power.

Third, there are life-cycle considerations here: the age-wealth profile tends to have a significant upward slope that generates substantial point-in-time wealth inequality that vanishes when we shift to the broader, much more appropriate life-cycle perspective.

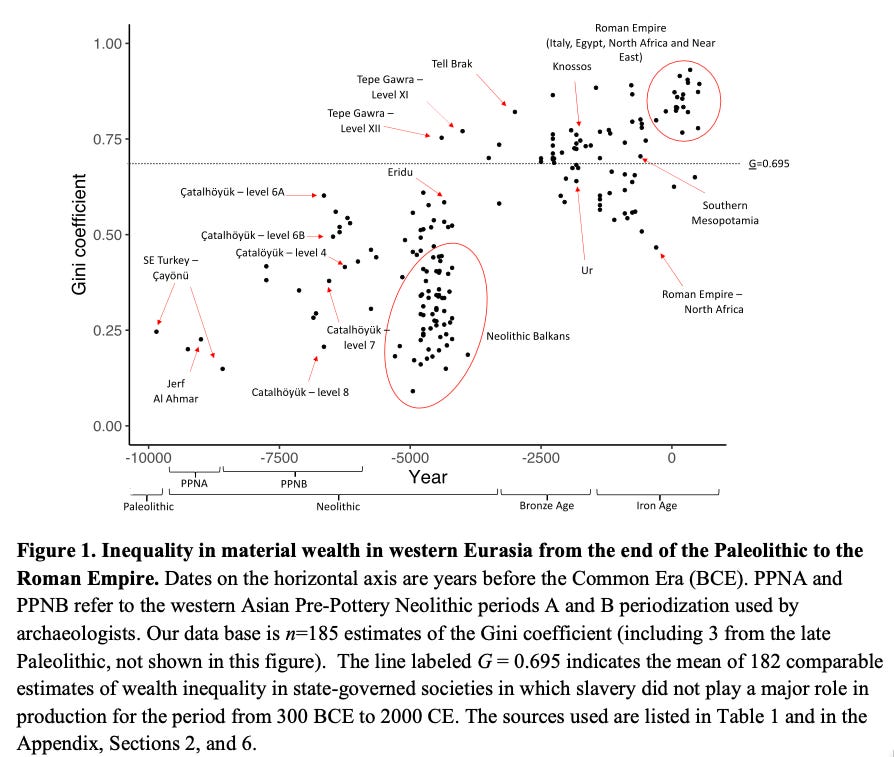

All that said, the conclusions—or, rather, the highly speculative hypotheses—that Sam and Mattia argue for are well set out in their Figure 6: they add to the standard inequality mechanisms of (a) domination by professional thugs-with-spears (and their tame accountants, propagandists, and bureaucrats), and (b) institutions of personal near-total subservience, i.e., slavery (ripping people out of their social context and placing them in a new one in which they have no social networks containing people obligated to assist them), a third: a shift from a labor-limited agrarian economy to a land-limited one made possible by the coming of the plough and the ox:

In their view, with the plough and the ox we see three things:

Amplified importance of shock to your wealth: with heavy up-front investments and annual fixed costs in feeding your animals, agricultural output variations have a much greater impact on the net product harvested.

Animals (and titles to extensive land) are easy to personally appropriate and then transmit via inheritance.

Transformation agriculture from what they Sam and Mattia call “labor-limited” to “land-limited”.

Why the first two would raise inequality is a simple matter of math. But what is this third? My first reaction is simply not to understand what they mean. These agrarian-age economies are, nearly all of them except on a colonial settlement or technological change frontier, very close to being fully Malthusian. In both situations people could raise more crops, eat better, and have more children if they had more land.

Perhaps I can make sense of this in a different way. With a hoe, you intensively plant, fertilize, weed, tend, and harvest. But if you have twice as much land you can only apply half as much labor to each plot, and so returns to extending your farm are not high. With a plough and with oxen, you can extensively plough, have the oxen fertilize, plant, and harvest. And if you get more land? Then you can get more oxen. Thus the marginal product of labor drops off much more slowly—as long as you are in a long enough run to be able to raise more oxen.

Sam and Mattia (and Amy Bogaard) argue that this shift not only plausibly raises the importance of shocks and the persistence of wealth differences via inheritance but also plausibly leads to shifts in culture and in what economists these days call “institutions”. From Bogaard, Fochesato, and Bowles (2019):

The third consequence… is indirect, operating via the cultural and institutional environments that are typically associated with a land-limited economy… increasingly autonomous households… the diminished importance of collective forms of co-insurance and risk pooling…. Livestock… are both valuable and long-lived… [and thus] savings, allowing an extended family practising large-scale herding to buffer shocks…. The increasing feasibility of wealth storage by individual households may have led the more successful families to withdraw from community-based sharing institutions…

What should we think of this argument?

We should think: perhaps.

First, we run headlong into the major problem of prehistoric sociobiology and biosociology: such claims are almost always just-so stories by which people project what they think of the present onto a distant past, of which we know very, very little, and assert much more strongly than they should that things must have been that way long ago.

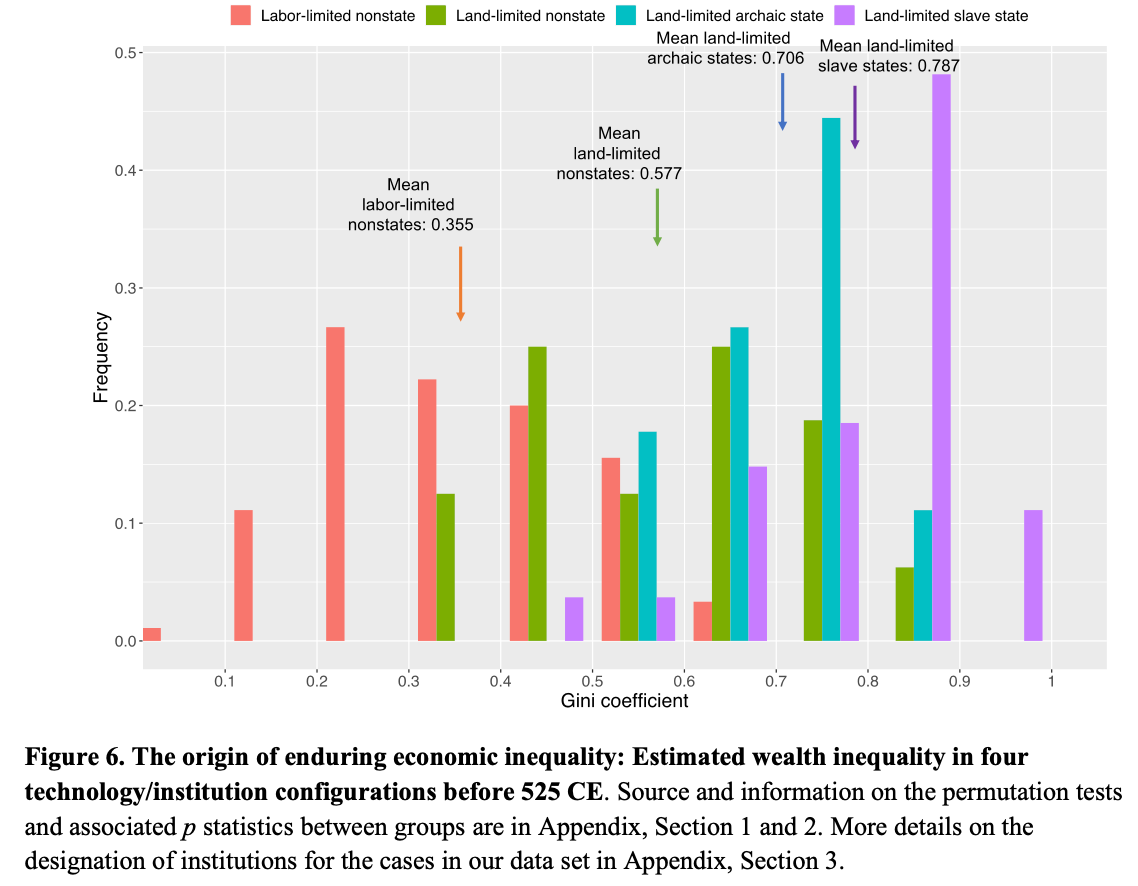

Second, attempts at empirical testing run into the problem that the geography of the Old World as far as plough vs. hoe is concerned prohibits you from saying anything with certainty more than plough-ness or plough-suitability is at least a plausible marker of important processes of diffusion of some sort. The plough spreads where there is sufficient soil, sufficient water, and a sufficient absence of intense animal parasites—but that spread is largely the same as the spread of all kinds of other features of human society via migration, trade, and contact as well.

Third, turn the question around: In what can inequality consist, other than in differential powers to manipulate nature and to gain the attention and command the coöperation of other humans? Inequality must be inequality in control over land and control over tools—silent tools, noisy tools, and speaking tools: instrumenta muta, instrumenta semi-vocale, and instrumenta vocale—useful objects, domesticated animals, and serfs or slaves. What else could it be?

In the Mesolithic Gatherer-Hunter Age, there can be inequality in tools—but not that much of it, for you are largely limited to what you can carry and what you can store in a way that resists weather as you make your circuit.

With the coming of the Neolithic Agrarian Age, with agriculture and animal domestication, you can get inequality in tools amplified—you are sedentary and so can pile up more usefult stuff—plus you can get inequality in the noisy tools that are herds, plus you can get serfdom—farmers cannot abandon their fields to run away from professional thugs-with-spears.

With the coming of the Bronze-Age state and large-scale war, you can get slavery as well: ripping people out of their social context and destroying their social power to make them obedient and compliant.

I would say that we have, here, five dimensions of acquisition and accumulation: tools you can carry, tools and implements at your farmstead, animals, the serfdom that is coërcion of farmers within reach, and slavery.

Is there much more going on here than simply an expansion of the dimensionality of the space of possible wealth inequality, and so we get more of it?

Perhaps…

Extra:

References:

Alesina, Alberto; Paola Giuliano, & Nathan Nunn. 2013. “On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough”. Quarterly Journal of Economics 128 (2): 469-530. <https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt005>.

Bogaard, Amy; Mattia Fochesato, & Samuel Bowles. 2019. "The Farming-Inequality Nexus: New Insights from Ancient Western Eurasia." Antiquity, 93(371), 1129-43. <https://www-cambridge-org.libproxy.berkeley.edu/core/journals/antiquity/article/farminginequality-nexus-new-insights-from-ancient-western-eurasia/8EFE3B8F5AFA07450F87E4E9B553A43E>

Bowles, Samuel, & Mattia Fochesato. Forthcoming 2024. "The Origins of Enduring Economic Inequality." Journal of Economic Literature. <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.20241718>.

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2024. “What Is a Gini Coefficient?” DeLong Notes & Scratches, February 23. <https://www.icloud.com/keynote/088ZgJXfSKqz4c4wq0gLJT0hw>.

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2024. “Basic Gini Coefficient Finger Exercises”. DeLong Notes & Scratches, February 23. <https://www.icloud.com/numbers/0f1BPu6Sph1r6oKsshIP_vtlg>

Flannery, Kent, & Joyce Marcus. 2012. The creation of inequality: How our prehistoric ancestors set the stage for monarchy, slavery, and empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wikipedia. Accessed February 23, 2024. “Corrado Gini”. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corrado_Gini>.

Zucman, Gabriel. 2016. “Wealth Inequality in the United States Since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data”. Pathways Magazine, State of the Union 2016. Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality. <https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/Pathways-SOTU-2016-Wealth-Inequality-3.pdf>.

While it's true that hunter gatherer societies have more equality, the unfortunate fact is that everyone in these societies tends to be equally poor. Since poverty is a relative term, the only way to avoid this problem is to keep the hunter gatherers isolated, so they have no one else to compare themselves with. I recall the line in the book "Guns, Germs, and Steel" where the New Guinea native asks the author "How is it you have so much cargo?" aka material possessions.

Improvements in agricultural productivity can go 3 ways. 1. enrich some relative to others in ways that are defendable and transferable (their thesis) 2. enable population growth to the point where production just supports the new population (the Malthusian solution is probably worse than inequality) 3. support growth in other industries that can absorb the population growth (some agricultural surplus goes to investment beyond agricultural technology). This is the story of economic development where other industries offer higher labour productivity. The modern development question is how to get labour out of agriculture to make investing in productivity improving technology worthwhile. Labour intensive export oriented manufacturing has improved income equality across countries, but increased it within countries. Can economic development be achieved without highly unequal growth?