COMMENT: What Are We Doing When We Teach "Political Economy"

Network for a New Political Economy Teaching Panel: 2021-03-05

As the last panelist—always a hazardous place to be—let me incorporate by reference all of the very good and interesting and true things have already been said by the previous panelists.

But let me not repeat them.

Let me not bore you.

Let me take a different tack: Let me ask: What are we doing when we do political economy?

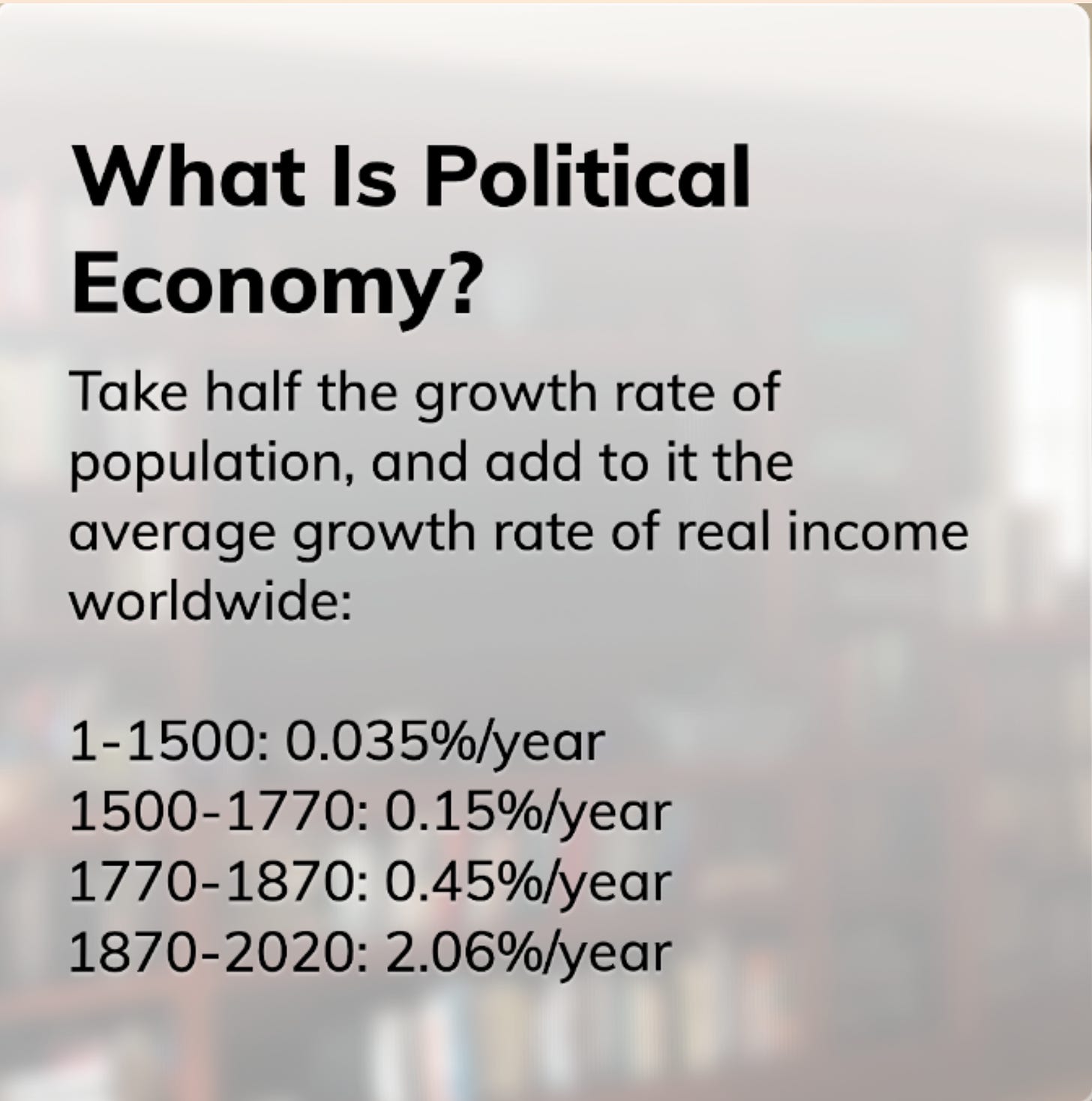

Here is one approach: Take half the growth rate of world population, and add it to the worldwide average growth rate of real income. Take that as an index of the power of the human race and its economy to manipulate nature and organize humans—in ways for good and for ill—worldwide. If you do that, you then find that:

from the year one to the year 1500 the average growth rate of that index is 0.035%/year: 35-one thousandths of a percent per year.

Shift to the the Imperial-Commercial Revolution Age 1500-1770, and find that the average index growth rate is something like 0.15%/year.

Move to the Industrial Revolution Century 1770-1970, and find that it is something like 0.45%year.

And for the past 150 years, since the date Simon Kuznets declared the start of the Modern Economic Growth age, it averages 2.06% per year.

We have, in a sense, more technological and organizational change in the world economy now in every two years than we had in any century back before 1500.

That makes me think this: Political economy is social theory in the age of this extraordinary transformation of technology, understood as human powers to transform nature—not always in a good way—and to organize humans—not always in a good way at all.

Note that it is not that economists or political scientists have any special expertise in figuring out what the appropriate social theory for this age of extraordinary transformation of technology is.

Sociology definitely has a major place to play: I was having a discussion with two other economists last week—finance economist Noah Smith and labor economist, Aaron Dube. I said something like: “Well, I have found, in thinking about these questions around the minimum wage and labor organization and so forth, that the most insightful person I ever took a course from was Mark Granovetter”. At which point Noah said: “That's interesting, because I was about to say the most insightful person I ever took a course from about this was Mark Granovetter”. And then Arin chimed in saying he, too, found that he'd been profoundly influenced in this by the course he took from Mark Granovetter.

We all three, at some fairly deep level thought, we were economic sociologists pretending to be economists, because we were all very conscious of the network sociological-underpinnings of things that economists would usually model as competitive market outcomes—and so understood why things like the low-wage labor market did not, when you looked closely at them, behave much like a perfectly competitive market in equilibrium at all.

Political economy is appropriate social theory for the age of this extraordinary transformation of technology in the economy, for the economy is changing and changing so rapidly and those changes ramify so far that they pretty much have to be at the core of whatever analysis you might undertake.

Now: rubber, meet road: What should we teach?

We want to teach complexes of ideas and linked chains of interdependence. We want to teach our students that there is not one jawbone of an ass with which we slay all of the intellectual Philistines we encounter. We need different tools and different approaches and different formal and informal models for different situations. Plus we are storytelling animals: We need human protagonists and narrative plots if we are to remember much of what we might learn. That means that it is inevitable, if we are to teach well, that we hang theorists’ names on different conceptual approaches, never mind that doing so is never fair to the theorists so Procrusteanized.

And should we follow the Barrington Moore model? Should we, as Alan Karras strongly advocated, make our students read big, difficult books? It is true that reading big, difficult books is a very important skill, and is enormously rewarding.

But that requires a very high degree of engagement from students. I, at least, have found that much harder to maintain over this past plague year.

The upshot? We do have to, in some sense, pick some theorists. Then show how we apply their theories—or rather theories and conceptual approaches that are named after them—to the elements of the real world that we want to study.

The question, then, is: Which theorists?

I have periodic discussions with Rakesh Bandari about how Hobbes, Locke, Smith, and Mill, in grappling with liberalism and its challenges in their day, evolved theories that are excellent for helping you to understand the world between 1640 and 1840. And, Marx, Weber and Durkheim—the core of the original version of the Barrington Moore political economy approach, the one I was exposed to way back in 1978-1979, when Shannon Stimson led seven of us through those books and others in Harvard’s Social Studies 10—molded my mind into a shape wonderfully prepared to understand and analyze the world of Northwestern Europe over 1840-1940.

If only I'd been plopped down in Northwest Europe in 1900!

People would have thought I was such a genius! But, unfortunately, I have been trying to deal with the world of 1985-2020.

Our students will hit the kind of peak of their influence of their careers, and of their desires both to change the world and survive in it, sometime around the year 2040. So who should we teach them? Who are say the three or four or five political-economy and social-theory theorist who will be the best guides to the world of 2040?

I for one, continue to be very, very impressed with the continued relevance of Karl Polanyi. Lots of people have thought me a genius over 2015-2020 whenever I open my mouth and make a Polanyian point.

I also am continually impressed by the continued relevance of John Maynard Keynes—but in large part that relevance has been generated by the economics profession’s rejection of Keynes after 1980, so that his ideas have had to be very painfully relearned. And do not see Keynes as a narrow economist: he is a political actor and a sociologist as well, and even—especially?—as an upper-class twit had many sharp perspectives on the nature and the worth and the cultural contradictions of the bourgeoisie and its capitalism.

But for the other three—let me leave them as question marks. I am looking for candidates…

Under the auspices of N2PE: Network for a New Political Economy: <https://twitter.com/N2PE_Network/status/1367943000639242241><https://newpoliticaleconomy.berkeley.edu>. Whole thing at: <https://github.com/braddelong/public-files/blob/master/nnpe-teaching-panel-2021-03-05.txt>