What Is the Ten-Year Real Rate Going to Be? II: Peering at the Future Fundamentals of the Flow-of-Funds Supply-Demand Balance

What are the odds that bond rates are going to return to the 2010s normal? Low, although at least some mean-reversion seems highly likely, plus in the future rates are likely to be lower on average...

What are the odds that bond rates are going to return to the 2010s normal? Low, although at least some mean-reversion seems highly likely, plus in the future rates are likely to be lower on average than today’s late-cycle rates. But what are the chances interest rates are only partly through a régime shi ft that the market is only recognizing slowly? There are four perhaps-sensible possible drivers of such a régime shift: (a) reversal of the Cold War-end peace dividend, (b) investment requirements for green technology, (c ) the coming of a new investment heavy GT-LLM-ML-driven leading sector, or (d) that the equilibrium rate is really a social and not an economic fact…

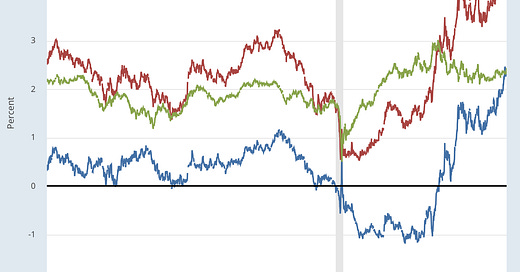

The 10-Year U.S. Treasury Bond’s real interest rate is now above 2% per year: time to worry about the deficit again?

Does that mean it is time to worry about the deficit again? On the one hand, perhaps not. With 1% per year future U.S. population growth, with a reasonable hope with policies aimed at actually boosting investment of 1.5% per year productivity growth, it is still the case that g > r unless you believe that we are still at mid-cycle—that interest-rate increases still have a way to go, so that on average over future business cycles interest rates will be as high as they are today, or perhaps higher. And that is not where current judgment is, at least within the halls of the Eccles and the Martin buildings:

Tim Duy: Federal Reserve Governor Chris Waller cleverly raised the bar for another rate hike at the December FOMC meeting: ‘“I find myself thinking about two possible scenarios for the economy in the coming months. In the first, the real side of the economy slows. This is the scenario broadly reflected in the September Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) by FOMC participants, where an easing in demand helps bring the economy into better balance with supply and allows inflation to move closer to our 2 percent objective. In this scenario, I believe we can hold the policy rate steady and let the economy evolve in the desired manner…” This says that if the economic data supports an outcome broadly in line with the September SEP, Waller doesn’t see a need to hike rates even though that same SEP projected another rate hike…. To be sure, the Fed wasn’t going to say directly it wouldn’t hike in December, but by raising the bar to a rate hike, Waller makes the September SEP no longer valid. It’s not the guide for another hike…. [And] Waller arguably raises the bar… even further…. Low inflation or low growth alone is enough to forestall further hikes…

Thus the current central case is that, while we can no longer realistically hope that we will grow out of deficits without taking any action, reducing the rate of growth of the nominal national debt is only worth doing to the extent that we think we need insurance. Insurance against what? Either against another large macroeconomic shock further steepening the slope of the intertemporal price system, or in order to provide extra fiscal space to meet some future emergency requiring additional mammoth government spending in which it is, somehow, not appropriate to pay for that additional tranche of spending via higher taxes at the time.

On the other hand, there is the possibility that we are still only part of the way through an economic régime shift, which is now-ongoing but only half-recognized, that is pushing up the long-run average future value of the 10-Year US Treasury rate—and that will push it up still further. It is too soon to focus on that possibility. But it is not too soon to say perhaps…

What factors might be driving such a shift?

Last time I argued that there are four factors that determine the future value of the 10-Year US Treasury rate: [1] the true equilibrium rate, [2] expected inflation, [3] the safety interest rate discount, and [4] the stance of the Federal Reserve. I argued that the ebbing of temporary factors associated with [2], [3], and [4] were likely to put 0.5%-points of downward pressure on the 10-Year Treasury, which is currently at 4.7%. However, that leaves the rise from 2.5% in the 2010s to 4.2% remaining. That leaves only [1].

And I ended last time with a question: Is that large 2.1%-point increase consistent with changing fundamental factors that have increased the true fundamental “neutral” equilibrium rate, the one that balances savings and investment in a full-employment economy?

By coincidence, I again see four factors—I see four perhaps-sensible arguments for believing that the bulk of the interest-rate rise is a result of changing fundamentals:

One perhaps-sensible argument for a higher neutral interest rate in the future is the reversal of the Cold War-end peace dividend that we harvested in the 1990s. This shift in spending had a positive effect on economic growth and productivity, as well as a lowering effect on interest rates. However, in recent years, the geopolitical situation has become more unstable and uncertain, leading to a resurgence of military tensions and conflicts. The US government may need to increase its defense spending to maintain its security and global leadership. Or the US government may not need to, but may be convinced that it needs to. Such a peace-dividend reversal could put upward pressure on inflation and interest rates, as civilians made poorer save less and the government and defense contractors invest more. The problem with this argument was that the high Cold War years of the Korean and Vietnam Wars and the Space Race did not see noticeably higher real interest rates. Thus the real argument has to be: “National security” lobbies will succeed in pushing through much higher defense spending without offsetting tax increases. Perhaps. But that would require dominant congressional coalitions willing to vote for military spending only rather than military spending-plus-tax supplementals. My read of the Congress is that

there are many Democrats who could be convinced to be deficit hawks coupling tax increases to military spending supplementals,

there are enough Republicans of whom Vladimir Putin has videos of them doing things in the Moscow Ritz-Carlton, and so

there is no reason to think that extra spending for Cold War II will be debt-financed at the margin.

But I could be wrong here.

Another perhaps-sensible argument for a higher neutral interest rate in the future is the likely or hoped for investment in green technology and in repairing the damage to be caused by global warming. The US economy faces a major challenge from global warming, which poses significant risks to its environment, health, infrastructure, and security. Policies and programs to fight global warming may well require large-scale public and private investment: renewable energy, electric vehicles, carbon capture, and energy efficiency. More demand created for scarce investment resources, especially if financed by more debt incurred, boosts investment relative to savings and so raises the neutral rate.

Again, perhaps. But only perhaps. We may well wind up not making the desirable investments—to our great loss, and with the consequence of greatly slowed economic growth bringing a lower r* with it. And whether green investments will wind up being large, heavy, and expensive or small, light, and cheap is, from our current perspective, in the lap of Tykhe.

A third perhaps-sensible argument for a higher neutral interest rate in the future is the possible jump in productivity due to what I do not like to call artificial intelligence (call it GPT-LLM-ML instead: general-purpose transformer models, large-language models, and machine-learning models). Enhancing human capabilities, automating tasks, improving decision making, and generating new insights and innovations—these are potentially powerful benefits that could lead to higher economic growth and productivity, as well as greater demand for funds to invest. But I do not see this at all. GPT-LL-ML investments seem, to me at least, likely to substitute for investments in dumb materials by virtue of their ability to—perhaps—make our materials smart. Yes, GPT-LLM-ML will cause lots of chips to be made and lots of (hopefully green) power to be generated. But boosting investment demand in total, across all sectors, relative to savings supply, by a substantial magnitude? I do not see it. The bull cases for GPT-LLM-ML seem to me to have it raising the economy’s growth rate g by much more than it raises any r* neutral interest rate concept. So this one is a factor of interest, possibly, to bond traders. But not a factor to weigh heavily on the minds of those thinking about other issues.

The fourth perhaps-sensible argument is that investment spending (and consumption spending!) continue to be higher than expected, conditional on the current level of interest rates. People are seeing something that is making them more optimistic about the future—and are spending. They think r* is higher, and if people permanently think r* is higher, it is, whether or not there is good reason for their thoughts. This is a very, very hard argument to refute, or even to think about. It is that the market-equilibrium interest rate is much more a social fact, without secure grounding in technologies, or in permanent or persistent factors affecting human utilities and behavior, at least as we neoclassical economists think of it. Hi, at least, can get no purchase on this argument. So I throw it over the wall to the sociologists and psychologists, and hope someone over there catches it.

There are also less credible arguments:

That the neutral interest rate will be higher because it has been unnaturally and artificially depressed since the 2008 financial crisis.

That governments will run higher stimulative government deficits in the future, requiring tighter monetary policy to offset it.

That the Fed’s quantitative-tightening (QT) program will materially alter the supply-demand balance.

I find these less credible because (a) the original quantitative-easing program was very weak tea, and so I expect the same of its reversal; (b) government-deficit policy could go either way, with higher interest rates suppressing pressure for rather than resulting from deficits; and (c) there really is no “natural” interest rate separate from the “neutral” rate, and claims that interest rates “should” revert to a higher level require the identification of a mechanism to take them to that level—not an incoherent and wrong assertion that central banks are engaged in unsustainable price controls.

My guess is that markets think that growth and inflation revert to pre-GFC levels. BUT there's also a lot of momentum trading on the long-end of the curve which may not be around in 6-months, and could easily reverse. In the short run, a hell of a lot of securities market prices are trades, not investments.

All points well taken. However, could your third "perhaps-sensible" argument be rendered "sensible" by what is going on (mostly incipient, still) with American manufacturing? Given constraints on the labor input, might that not lift the K/L ratio in a way that raises, at least, the non-steady state productivity and economic growth rates by a few tenths of a percentage points? I understand that the outcome is still up in the air, and we may not know the marginal product of capital until we see it. But given what we've been seeing on that front so far is unlike what we've seen in a very, very long time, it may yet deliver the goodies (but don't know when).