Yes: This Is Worth Signing: Economists Who Are Neither Bought Nor Crazy Oppose Broad-Based Tariffs

Broad-based tariffs are really not a good idea at all. As I was writing in email earlier this morning in response to “economists are much better at saying what is wrong with tariffs than proposing...

Broad-based tariffs are really not a good idea at all. As I was writing in email earlier this morning in response to “economists are much better at saying what is wrong with tariffs than proposing alternatives to tariffs… which means that Trump is the only game in town”: “Actually,public investments to support the development of communities of engineering practice have worked very, very well indeed for the past 225 years when applied by an even semi-competent bureaucracy: public-sector commitments to be a lead purchaser, ports and roads, schools, a sensible regulatory framework for a banking system, and a commitment to maintain full employment have all worked. Broad tariffs have not. Think of them as radiation. Properly and narrowly focused, a gamma knife can be useful. Whole-body blast irradiation is not…

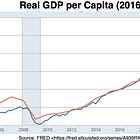

As I said earlier today, Trump’s international economic policy is very much like BREXIT—pointless chaos and disruption to highly productive international economic integration. It is not clear to me whether the policies Trump wants to implement are equivalent to a single, a double, or a triple dose of BREXIT because we have no good idea of what the policies Trump wants to implement actually are. Probably the United States is less vulnerable to policies of pointless chaos and disruption of international economic integration than the United Kingdom was. Probably. But do recognize that BREXIT was a big deal: it has cost the United Kingdom something between 5% and 15% of its potential prosperity:

<https://bit.ly/Gramm-Summers>

A Letter on Tariffs From Economists to Trump

Like our predecessors in 1930, we oppose the use of tariffs as a general tool for economic policy.

Phil Gramm & Larry Summers

Jan. 30, 2025 1:55 pm ET

In an extraordinary act of unity, 1,028 American professional economists in the spring of 1930 signed a letter urging Congress to reject and President Herbert Hoover to veto the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. Yet that June, Congress passed it and the president signed it into law. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff helped turn a stock market rout and a building financial crisis into a worldwide depression and triggered a global trade war that halved American exports and imports.

Today, we write this letter in a similar spirit of unity. While the professional economists who have signed today’s letter differ on many issues, we are united in our opposition to tariffs as a general tool of economic policy. Even in efforts to promote national security, tariffs are prone to abuse. Many of the worst restrictions on trade, such as the Jones Act, have been implemented in the name of promoting national security.

Our united opposition to non-defense-related tariffs is based not on our faith in free trade but on evidence that tariffs are harmful to the economy. Protective tariffs distort domestic production by inducing domestic producers to commit labor and capital to produce goods and services that could have been acquired more cheaply on the international market. That labor and capital are in turn diverted from producing goods and services that couldn’t be acquired more cheaply internationally. In the process, productivity, wages and economic growth fall while prices rise. Tariffs and the retaliation they bring also poison our economic and security alliances.

The primary argument for the implementation of broad-based tariffs is that they will reverse the hollowing out of American manufacturing and reduce the trade deficit, which is causing a “hemorrhaging of America’s lifeblood.” Contrary to the repeated claim, there has been no hollowing out of American manufacturing. Industrial production in the U.S. is at an all-time high. The U.S. is producing 2.5 times as much real industrial output as it did when we last ran a trade surplus in 1975. We are producing that record output with the smallest percentage of the labor force involved in manufacturing since America became fully industrialized. The percentage of the civilian nonfarm labor force employed in manufacturing peaked during World War II and has been in secular decline ever since. This has been a great success for productivity and not a failure of trade, as today’s full employment attests.

It is telling that the Trump tariffs implemented in mid-2018 and the Biden expansion of those tariffs didn’t stop the secular decline in manufacturing employment as a percentage of the total labor force. The decline in manufacturing employment as a percentage of total employment is being driven by the same secular forces that caused employment in agriculture during the 20th century to fall from 40% to 2% of the labor force: a vast increase in labor productivity and a decline in the demand for manufactured products relative to services. This is a worldwide phenomenon occurring in both developed and developing countries.

In the long history of the country, there is little evidence to substantiate the claim that America prospers more when trade deficits fall than it does when they rise. During the Reagan recovery, as the level of economic growth surged, foreign investment rushed into the U.S. and the trade deficit soared. The same phenomenon occurred during the Clinton boom: So strong was the attractiveness of investing in America that the trade deficit continued to grow even as the federal government ran budget surpluses. The annual real trade deficit nearly doubled during the four years in which the U.S. government was running a budget surplus. When the economy started to grow faster in 2017 and 2018 during the first Trump term, the trade deficit rose despite the tariffs that were imposed in mid-2018.

The tariffs on steel and aluminum created only a small number of jobs, but since for every worker in the steel and aluminum industries there are 36 workers employed in American industries that use steel and aluminum in production processes, those modest gains were offset by the jobs losses in industries that use steel and aluminum as inputs. With foreign retaliation, the estimated cost to the economy of jobs created by the 2018 tariffs on washing machines, steel and aluminum clearly amounted to many times what the jobs paid in wages.

In sum, tariffs don’t have a predictable effect of reducing trade deficits, and trade deficits aren’t necessarily an adverse economic development. Indeed, trade deficits often arise as foreign investors choose the U.S. as a preferred destination for their capital.

Foreign capital has always played an important role in American economic development. The history of America is the history of foreign capital—initially from Britain and Holland—and labor from all over the world coming together to create the American economic colossus. Foreign capital today performs the same role. The countries whose citizens today make the largest investments in America—Japan, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands—invest in the U.S. because they see the investments as being more productive than the alternatives in their home countries or elsewhere. At least in the modern era, it seems that when the American economy is working well, it becomes an irresistible magnet for foreign workers and foreign investors.

The argument that foreign investment is making America poorer flies in the face of recorded history. From the settlement of Jamestown, foreign investment has enriched America and those who have invested in it. A review of the economic history of our nation yields no credible evidence that broad-based tariffs have benefited the nation as a whole. Protectionists often point to the 19th century as a period of high tariffs and strong economic growth. But a close look at the data for the 19th century shows conclusively that the country industrialized fastest when tariffs were falling, not when they were rising.

Sound fiscal policy and effective incentives to work, save and invest can increase economic growth, but the implementation of broad-based tariffs impedes that growth and in a full-blown trade war would overwhelm it. While we have fundamental differences in our views of how to produce a sound fiscal policy and implement effective incentives for productive efforts, we are united in our belief that broad-based tariffs will impede economic growth, risk triggering a trade war, and inflict long-term harm on the economy.

We therefore urge Congress not to adopt the administration’s proposed tariffs and urge the president not to implement those tariffs by executive order. <https://bit.ly/Gramm-Summers>.

IMO, this letter is a waste of time, other than putting down a marker for a future "We told you so".

Firstly, the idea that tariffs will restore US manufacturing is a distraction, arguably a con to sell to the rubes in the "left behind" rust belt. It is really a way to create a flatter tax both by increasing consumption taxes and lowering high tax brackets. This is what Republicans have pushed for as long as I have lived in the US. "Flat taxes" are a recurring suggestion in right-wing politics.

Secondly, as Krugman again pointed out, the US is removing expertise. From "My opinions trump your facts", to SCOTUS reversing the Chevron Doctrine, to Trump and the Republicans gutting science-based agencies, and the elevation of anti-science political appointees, expertise is being discarded. We saw this in the Bush II administration, which is now a crisis. Economists have had a lot of power influencing government policy, but now that expertise will be ignored, just as earlier advice was ignored on tax cuts, which increased inequality while hindering the improvement for employees.

If Trumplicans can manage to continue to deny the existential threat of climate change, why would they listen to economists whose message undermines their tax-cutting goals for their donors?

An explosion of comments says everything, doesn't it? It looks like everybody agrees. It also looks like everybody disagrees. The ambivalent vibe is killing me.