DRAFT: What Is Going on wiþ China’s Economy?

No, I do not understand China's two generations of successful, economic growth; no, I do not know whether China is now in the middle income trap; I do suspect Adam chooses concept of "polycrisis"...

No, I do not understand China's two generations of successful, economic growth; no, I do not know whether China is now in the middle income trap; I do suspect Adam chooses concept of "polycrisis" may apply here. Some musings as I try to construct an informed view of the China situation for myself…

Smart no-longer-young whippersnapper Dan Drezner writes:

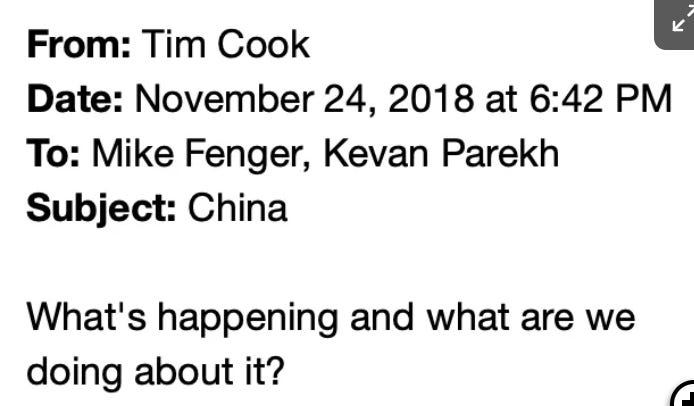

Dan Drezner": The End of the Rise of China?: it’s been impossible to go 24 hours this month without reading a piece noting China’s economic woes…. it’s been impossible to go 24 hours this month without reading a piece noting China’s economic woes…. Lingling Wei and Stella Yifan Xie… Rebecca Choong Wilkins and Colum Murphy… Catherine Rampell… The Economist… in its cover story… Ian Johnson[‘s] “Xi’s Age of Stagnation….. All of this is from the last ten days in August…. Earlier in the month… Adam Posen in Foreign Affairs, Peter Goodman in the New York Times, Paul Krugman in the New York Times, Keith Bradsher in the New York Times, James Kynge in the Financial Times, and the entire editorial board of the Financial Times…. Are there any China optimists left out there?… Nicholas Lardy… argues that, “[the] widely popular assessment is likely premature and, at least in part, perhaps simply wrong….. The combination of rising personal incomes and a falling saving rate means that future household consumption growth will likely surprise on the upside…”. Lardy’s… caution is well taken…. That said, even a modest increase in consumer spending cannot reverse two dominant problems…. First, China’s structural problems are very real… demographic decline… productivity… continu[es] to stagnate, its ability to crib technology and foreign investment… is ebbing… real… a huge mess. Second, China’s leadership under Xi does not seem to be prioritizing economic growth…. That does not bode well for a sustained return to healthy economic growth…. I wonder… if the discourse is starting to catch up to the reality that maybe, just maybe, Chinese power has peaked…

The extremely wise Arpit Gupta has a very, very very nice summary of the possible reasons why the Chinese economy will get stuck in the middle income trap—if it in fact gets stuck. He sees four reasons it might get stuck:

Authoritarian Expropriation Risk…

Structural Imbalances…

Real Estate Boom-Bust…

Soft Budget Constraints…

He concludes that a China that gets stuck in the middle-income trap does so because of “all four…. What’s common across all… narratives is that China’s growth story may be more brittle than commonly accepted”:

Arpit Gupta: What's Going on with China's Stagnation?: ‘Authoritarian Expropriation Risk…. Most economists would offer a version of this incentives story when articulating why only democracies (and resource rich countries) have passed the middle-income trap… [perhaps] really a Xi Jinping problem… crackdown on… “soft”… in favor of “hard” tech, along with disappearing Jack Ma…. Structural Imbalances—China… too dependent on investment relative to consumption… has grown only by… pushing down… investment productivity… a weak social safety net, ensuring… precautionary savings… financial repression…. Real Estate Boom-Bust… heading for a crash, and China may be headed for years of weak growth ahead…. The Soft Budget Constraint…. Loss-making enterprises (whether formally public or private with public characteristics) are not allowed to fail, and this expectation infects all firm decisions… because firms all get bailed out, and continue operations as zombie entities….

I think all four stories likely play a role…. This last story... that China in the same category as Communist countries which were able to grow and achieve some structural transformation, before ultimately flaming out due to fundamental political economy… remains undercovered…. What’s common across all these narratives is that China’s growth story may be more brittle than commonly accepted, and to fix it may require politically challenging reforms to both the underlying economic and political model….

[But remember:] the rapid period of economic growth in the last several decades is one of the best things to ever happen to humanity…. China remains a very high performing economy… traditional sectors of manufacturing… increasingly in renewable energy… EVs… airplanes… AI, semiconductors, digital platforms, and so forth—far beyond what most economists would have thought possible under a Leninist one-party state…

What do I think?

First of all, China may well not get stuck.

It may pull on through.

A huge science, technical establishment, coupled with the worlds greatest concentration of engineers focused on process technology improvement and a 1.4 billion person market to provide the scale to wring all possible benefits out of process improvements and initial leads in frontier industries—all that may wind up leading China to do vis-à-vis the US over the next sixty years as the U.S. did vis-à-vis Britain from 1870 to 1930. People back in 1870 might well have said that the United States had second-rate universities and third-rate science, a corrupt version of crony capitalism focused on robber-baron rent seeking, no state capacity worthy of the name, and a bitterly divided population—yankees, white southerners, Blacks, immigrants, and new waves of future immigrants different from and hence alien to the old immigrants—which a creaky political system designed for the previous century was unlikely to be able to manage.

While that was a plausible view of the U.S. around 1870, it was a wrong one.

Thus China may surprise us.

China has certainly already over the past fifty years. It has astonished the world and absolutely flabbergasted me.

Remember: back in 1980 I thought that China had a working short-run development model and the legacy of the Maoist version of really-existing socialism had left it with enormous but easily correctable economic deficiencies. Thus I expected Chinese growth to astonish the world over the next five to ten years:

But then I expected the development model to lose steam. The systemic structural and authoritarian politics governance deficits of China seemed to me to make it make successful continuation of that development model beyond a 10-year horizon very unlikely indeed. The closure of society that the maintenance of party domination requires would break the developmental model.

First, agricultural de-communization would mean that there needed to be some way to rapidly reemploy workers no longer needed on low-productivity communes. How was the government to survive the social stresses? It did so via borrowing the entrepreneurial class of Hong Kong, and building good-enough institutions for investment and private enterprise that aligned local party élites on the side of growth rather than exploitation via the TVE framework.

Second, later, how was a all-thumbs communist system going to be able to do for the cities what the Soviet Union never did—get the goods to people who were not politically well-connected? The answer was to transform China’s cityscapes via an extraordinarily rapid and successful process of retail decontrol.

Third, later still, as of the mid-1990s the heavy-industrial state-owned enterprises of the Chinese state and their losses and their debts were simply too large a drag on the economy to be sustained, but shutting them down would produce the potential for enormous social dislocation and uproar—a Generalissimo Ludd, perhaps. But they did it. They shut them down. And, borrowing the entrepreneurial class from Taiwan this time, the private-sector and local-government and mixed busines and ownership forms had reached sufficient scale to absorb the workers.

Fourth, as of the end of the 1990s the gap between urban and rural living standards had grown so great that upwards of 150 million migrants were flooding into the cities. The 1998 decision to privatize new urban housing construction and to incentivize local governments to coöperate by tying their funding to development created places for the inmigrants to live, and the decision to go for the export-growth model coupled with the coöperation of the George W. Bush administration in the (bipartisan) hope that a China that rapidly became richer would ipso facto acquire a powerful-enough bourgeoisie to remain peaceful and become liberal.

And yet now it all seems to have shifted. Energies that would otherwise have been entrepreneurial are now being devoted to ascending within the party, controlling non-party elements, and (for outsiders) figuring out the right way to bribe party members with power in the present and the future to leave your business alone—perhaps in most part by giving their relatives a share of it.

And that is when those with entrepreneurial energy do not decide to just leave, and set up shop elsewhere, perhaps in Singapore.

China’s development model was, after all, only rescued in its first decade by the existence of Hong Kong’s entrepreneurial class, grown out of those who got out of Dodge City before the PLA arrived and sent those who remained to reëducation camps, at best. and its willingness to play ball. It was only rescued in its second decade by the existence of Taiwan’s entrepreneurial class, and its willingness to play ball. It was only rescued in its third decade by the willingness of the WTO to play ball with China’s development model. And it has only been rescued in its fourth decade by various low-quality investment bubbles.

Still, the system has held together. China has managed to mobilize resources on a truly titanic scale. And it has created a bourgeoisie—a bourgeoisie that has not felt that it has the need or the power to flex muscles for political dominance, but has been willing to focus, on an individual case-by-case basis, in cementing protective links with their party-side patrons.

I keep reaching for historical analogies, and I don't find any good ones. The rising bourgeoisie of Europe's imperial-commercial age led to the development of the absolutist monarchies that, in Engels’s famous formulation, held the balance between their aristocratic-military-police-control classes and their wealth=creation classes: the “relative autonomy of the state”. But it was those monarchs that ceded power to and promoted the rise of the bourgeoisie most rapidly that were by far the most successful in the long run. The relative autonomy of the state was real, but, where it was exercised in favor of the aristocracy, consequences for development or destructive for national development.

(Prussia in the 1800s is the only exception. But that is because in 1814 Austrian Foreign Minister Metternich handed the Junkers and the Hohenzollerns the Rhineland and the Ruhr. Metternich, fighting the last war, thought it very important that Prussia be more focused on containing France than Austria. Big long-run mistake—not in Metternich’s day, but a generation after his forced retirement. Do note that, had I been on Henry Kissinger’s dissertation committed, I would have rejected the dissertation without a chapter on the long-run consequences for the Austrian Empire of handing the most economically dynamic regions of greater Germany to Prussia. And I do think that there is definitely a book to be written about how reactionary governments in Berlin and Vienna in the 1800s did not do more to hobble industrial growth in the Ruhr, in Silesia, and in Bohemia.)

Gupta does not think much of Authoritarian Expropriation Risk…

The main challenge with the “expropriation” view is that there are surprisingly no obvious signs for incentive problems in China holding back wealth generation—R&D spending is huge, entrepreneurship is massive, and China is home to more large digital platforms (Alibaba, etc.) than Europe….

But Adam Posen does. He sees Xi Jinping as following “Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and Vladimir Putin in Russia… down this well-worn road…

Gupta also does noit think much of Structural Imbalances view of Michael Pettis and Matt Klein:

[The] challenges… [to] the “imbalances” view… [are that it is] not obvious how greater domestic consumption spending is going to further future productivity growth…

I think somewhat more highly of this view. Underlying it is a belief that you need to shift your demand into a configuration in which you are spending money on sectors where there are technological research and development externalities. Export industry had such. Infrastructure and construction by and large do not. And China is ideologically opposed to raising the private-consumption share of production.

This view shades into the “real estate bubble” view of:

Noah Smith… as well as Ken Rogoff…. China only kicked the can down the road in 2008, allowing a real estate bubble…. But now this is heading for a crash, and China may be headed for years of weak growth ahead….

And Òscar Jordà, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor would say not “years” but “decades”:

Òscar Jordà, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor: The great mortgaging: housing finance, crises and business cycles: ‘Disaggregated bank credit for 17 advanced economies since 1870…. Financial stability risks have been increasingly linked to real estate lending booms, which are typically followed by deeper recessions and slower recoveries...

Heavy real estate debt loads, unless quickly resolved, appear to be poisonous for medium-term growth, and perhaps beyond. (Note that this is true in a sense in which it does not appear to be true for government debt.) in China, this channel would be amplified by the interaction between real-estate busts and local government’s ability to do its job.

And as for the last story? I agree with Gupta that:

[Seeing] China in the same category as Communist countries which were able to grow and achieve some structural transformation, before ultimately flaming out due to fundamental political economy… remains undercovered…

In addition, I think there is a fifth factor. Xi Jinping is 70. There are valid complaints that the United States is too gerontocratic, but the open-speech nature of nature of political contestation greatly moderates the extent to which no-longer-rational aged decision-makers’ erratic choices cause lots of damage.

In autocracies, there is the erratic-aging-emperor problem. And there is also the loss-of-control to an illegitimate power-broker problem. We are told that Tiberius Cæsar started to lose control of Rome to his Prætorian Prefect Sejanus in the year 23, when he was 65, and much more so after the year 26 when he (mostly) withdrew to Capri. (Tiberius reasserted control by executing Sejanus in the year 31, when he was 73; and thereafter he lived for five more years—although it is not clear how much sway was exerted by Sejanus’s successor Macro and by Antonia Minor.)

Perhaps this is a case in which Adam Tooze’s concept of “polycrisis” is of great value?

Loved it all.

But Brad, we may have an imminent problem at hand. I've been looking at a lot of the price categories (consumer, producer and wages, annual % changes or year-on-year % change). The best of consumer price are advancing at a sub-1%-2% rate, more of them at sub-1% than sub-2% (exception: tourism and traditional Chinese medicine (go figure!)). The headline consumer price index is deflating. Most producer prices, by industry category, are deflating too (exception: non-ferrous metals i.e., mainly precious metals and rare earth elements, liquor, refined tea and tobacco). Urban employment has stalled or is falling. Wage growth has slowed markedly, though still positive. The dreadful sense I'm getting is that of a burgeoning downdraft in most all prices.

Question: Do policymakers in China know the meaning of a General Glut?

They're tinkering around with interest rates, mortgage rates and with little-bitty changes to this that or the other.

China has the typical problems of a middle income nation, plus demography, plus authoritarian roots, plus oddly aggressive international relations. Most are tough to solve; at best some are half-solved and some they live with. In which case, China slows, but still functions pretty well.

The biggest and most unusual problem is that I can't tell that Xi cares about solving any of these problems. His only interest appears to be personal power, not national, economic, or social. The rumors I hear are of huge layoffs in provincial governments, gone are the large bonuses that were expected in public, private, and SOE sectors, base wages that are not sticky like in the US, and electronic bank transaction sizes are severely throttled. Even if these are mere rumors, the result in confidence is there will be little private investment or discretionary consumption, and this is independent of the crises in real estate and infrastructure. Which is why I think China's economy threatens to seize up faster (in years rather than decades) than any large peacetime economy I can think of. China is the worlds biggest builder and manufacturer, and they consume half of the world's industrial commodities, so this must have contagion. Commodity exporting nations often have high debt and weak currencies, so I expect we'll see problems there in the next couple of years. Then the question will be, who holds those debts? Another contagion is to other manufacturing export nations who struggle to compete with a China that cuts both its currency and its domestic wages.

The tragedy is what China and the world could have been with a different leader.