England ca. 1900 as the Only True Steampower-Industrial Society EVAR

On the "Sonderweg" of the Anglo-Saxons...

On the "Sonderweg" of the Anglo-Saxons…

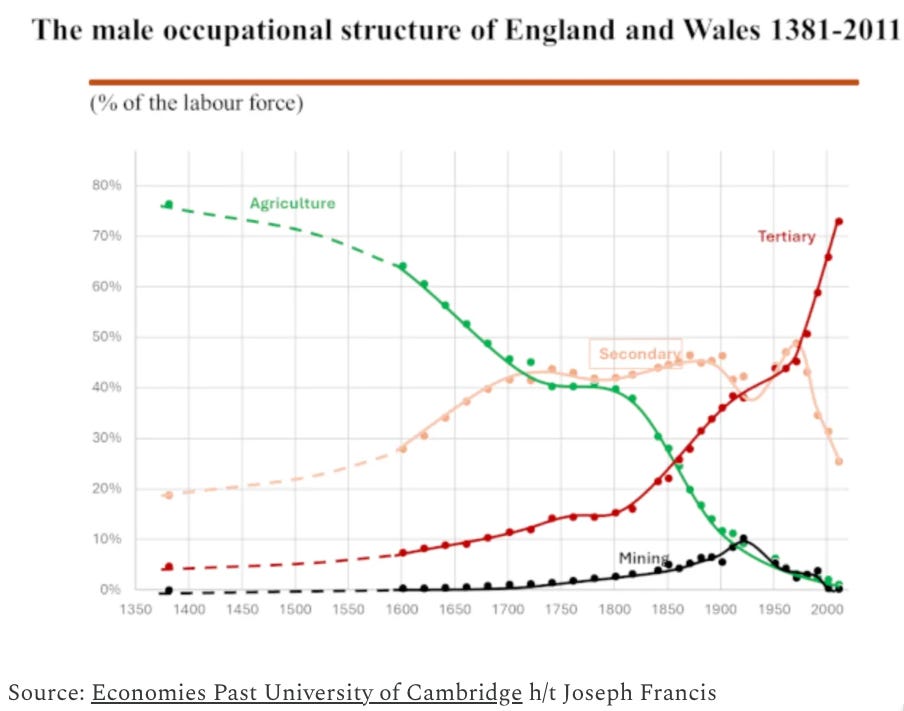

Adam Tooze <https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/top-links-399-industrialization-before>, following a tip from Joseph Francis, sends us to: Economies Past at the University of Cambridge:

CAMPOP says:

Primary sector: agriculture, forestry and fishing;

Secondary sector: mining, manufacturing and construction;

Tertiary sector: anyone in services.

That has got to be wrong—on the graph, “mining” does not appear to be included in “secondary”: their “secondary” measure appears to be manufacturing and construction only. If it includes mining, things simply do not add up.

My first thought is that this chart should be accompanied by one (at least before the 1900s) showing total employment by sector would be as illuminating. Both the relative share and the absolute numbers shed a lot of light on each other and on what went down.

The population of England and Wales grew from 2.75 million or o in 1500 to 4.25 million in 1600, 6 million in 1700, 9 million in 1800, and to 32 million in 1900, after all. As many people were employed in agriculture in 1900 as had been in 1800, after all. And the stability of the manufacturing and construction share is half due to the English population explosion that really takes off in the later 1700s, and does not reflect any kind of stasis of the manufacturing sector.

Still, this chart does show elements of English development that should be your focus to understand England’s trajectory:

The extraordinary agricultural-productivity revolution of the 1600s and the consequent lower relative demand for labor in agriculture.

The rise in manufactures—half to provide something to trade for food (because even with the agricultural revolution food production at home could not fully cope with rising demand from population and wealth), and half because manufactures were the goods most in demand to employ the 10%-points or so of the labor force notionally released from agriculture vis-à-vis some non agricultural-revolution renewed Malthusian-crisis counterfactual.

The extraordinary role played by mining.

The rise of the tertiary, services sector (which we really do need to subdivide!).

Thus the extent to which the Industrial Revolution in England (and Wales) is more a demographic and a globalization proces than an industrial-productivity process—an agricultural-productivity revolution which triggers a population explosion which then outruns even revolutionized agriculture and induces a wheel to manufacturing and manufacturing exports to get the money to import food for the population, à la Clark (2001).

Thus the extent to which the modernization experience of England is not one that would thereafter be undergone by all countries. It is not the case, as Karl Marx claimed in the 1867 Preface to Capital, that “the country that is more developed industrially only shows, to the less developed, the image of its own future…”

Rather, as Jeff Weintraub channeling Krishan Kumar taught me long ago, England had its own Sonderweg. England had its own separate path of development, its own sundered-way.

England was for a time around 1900 in fact the only true steampower-industrial society there ever was or ever would be, others going directly from agrarian-commercial (with industrial elements) to applied-science (with industrial elements) societies.

No, I cannot find my marked-up copy of Kumar right now—it is either in a box, in the basement, in the guest bedroom, in Blum Hall, in Evans Hall, or lent out and never returned. Ah. Here it is. The Internet Archive <http://archive.org> comes through yet again!

Kumar: “Evidence from dates as widely scattered as 1801 and 1841 were quoted as illustrative of the same point. Minor movements… [and] isolated crimes… were all built up into a quite misleading picture of the development of a ‘social war’ of revolutionary proportions… set down side-by-side with an account that so emphasized the brutalized and degraded condition of the working classes that it was inconceivable that they could play the role of revolutionary liberators written in for them in Engels’[s] epic drama.…. Given Engels’[s] purpose, there cannot be great reason to complain. The. [Condition of the Working Class in England] indeed remains… vivid, superbly written and in many ways remarkably accurate…. But to make this rhetorical and dramatized account a main ingredient in a model of the industrialization process in general, as later sociologists were to do, is to give it a status it did not earn…. It was bound to be dangerous to start off, as many twentieth century sociologists did, with a preconceived model of ‘modern industrial society’, put together out of the bits and pieces of nineteenth-century European development; and to judge the progress to ‘modernity’ of other societies in its terms…”

References:

CAMPOP. 2024. “Economies Past”. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. <https://www.economiespast.org/>.

Clark, Gregory. 2001. “The Secret History of the Industrial Revolution”. Davis: U.C. Davis. <https://faculty.econ.ucdavis.edu/faculty/gclark/papers/HEG%20-%20final%20draft.pdf>.

Engels, Friedrich. 1845. The Condition of the Working Class in England. Leipzig: Otto Wigand. <https://archive.org/details/theconditionoftheworkingclassinengland1845>.

Kumar, Krishan. 1978. Prophecy and Progress: The Sociology of Industrial and Post-Industrial Society. London: Allen Lane. <https://archive.org/details/prophecyandprogress>.

Marx, Karl. 1867. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. I. Hamburg: Otto Meissner. Trans. Samuel Moore & Edward Aveling. Ed. Friedrich Engels. <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/index.htm>.

Tooze, Adam. 2024. “Top Links 399”. Chartbook. April 7. <https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/top-links-399-industrialization-before>.

I'm a bit unclear as to the critical difference between the experience of England and that of later industrialisers like Germany.

Would it follow that the Engels' pause was peculiar to the UK? Or at least longer?

It would be interesting to know how many were drawn from agriculture to manufacturing because of the commercial revolution. A good index for this might be the number of people employed in the merchant navy.

My understanding is that many of the advances in agricultural productivity were borrowed form the low lands. Would be interesting to see if pattern of employment shifted there in the same way.