INCOMPLETE DRAFT: LONG NOTES TO: Introduction. My Grand Narrative

For "Slouching Towards Utopia?: An Economic History of the Long 20th Century", Basic Books, September 6, 2022

I think I stole the title from Simon Auerbach from an article he wrote back in 199. And the extremely insightful George Scialabba grabbed it for an essay title four years ago. And of course Didion:

1) Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991, London: Michael Joseph, 1984 <https://books.google.com/books?id=2-YQd5u86qYC>.

Reading Hobsbawm and thinking “no—that’s not the right story” put one of the bees in my bonnet that has led, in the fullness of time, to this book.

There is barely a paragraph in the book that has not been the subject of fierce controversy, or that’s point-of-view has not been rejected as wrong by thoughtful and learned historians, or that is at the very least massively over- or understated. So I acknowledge that smart people of goodwill can deliver trenchant and largely-unanswerable criticisms against nearly every single paragraph.

And I very much hope they will do so: it is one of the few ways that I can learn.

2) Also seeing a “long” twentieth century as most useful is the keen-sighted and learned Ivan Berend, An Economic History of Twentieth-Century Europe: Economic Regimes from Laissez-Faire to Globalization, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006 <http://books.google.com/?id=dK44ciNfx6MC>, who makes his choices for essentially the same reasons that I do. He, however, confines his book to Europe, and both gains and loses thereby.

Giovanni Arrighi (1994): The Long Twentieth Century (New York: Verso) <https://archive.org/details/longtwentiethcen00arri>, on yet another hand, pushes the origins of the long twentieth century back to 1500 and medieval Genoa. There are 324 pages before his “Epilogue” begins, yet it is only on page 239 that we get to:

The strategies and structures of capital accumulation that have shaped our times first came into existence in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. They originated in a new internalization of costs within the economizing logic of capitalist enterprise. Just as the Dutch regime had taken world-scale processes of capital accumulation one step further than the Genoese by internalizing protection costs, and the British regime had taken them a step further than the Dutch by internalizing production costs, so the US regime has done the same in relation to the British by internalizing transaction costs…

Thus I cannot buy into his analysis because he sees the history of the long twentieth century as largely an intensified repeat of earlier cycles of internal capitalist development led by a hegemon—Genoese, Dutch, British, and now American. That is the grand narrative he tells, engagingly and convincingly. But it is definitely not mine, and I definitely do not think it is the most important thread

3) Friedrich A, von Hayek, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” American Economic Review Vol. 35, No. 4 (September 1945), pp. 519-530.

…the proportional rate of growth of my index of the value of the stock of useful ideas about manipulating nature and organizing humans…: In the aggregate growth-modeling tradition that has developed from Robert Solow, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 70, No. 1 (Feb., 1956), pp. 65-94 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1884513>, the level of real net output per worker Y/L, with Y for net output and L for the labor force, is a simple mathematical function of the capital-intensity of the economy K/Y, of how much of produced means-of-production K per unit of net output there is assisting workers in creating that output per worker; and of the efficiency of labor E:

Y/L = (K/Y)^(⍺/(1-⍺)) E

Such an economy will tend to converge to a steady-state growth path in which the capital intensity K/Y approaches its steady-state value (K/Y)* given by:

(K/Y)^* = s/(n+g)

Where s is the net savings-investment rate of the economy, n is the proportional rate of growth of the labor force L, and g is the proportional rate of growth of labor efficiency E. (Yes: you usually see this equation with a “δ” in the denominator for the depreciation rate on capital, and with Y defined not as net but gross output, and with s defined as the gross savings rate out of gross output. But—as Solow pointed out to me, and has Piketty has stressed—while there is reason to think that having people save a constant proportion of their net output is a reasonable baseline case to start from, there is no reason to think that people save a constant proportion of their gross output—that net savings would be less in an otherwise-identical economy where capital equipment just happened to be less durable.)

The efficiency of labor E can then be thought of as a function of the level of knowledge about “technology” H—discovered, developed, and deployed ideas about manipulating nature and organizing humans—and of resources per worker R/L, where more resources per worker allow humans to be more productive, and where increasing resource scarcity leads to a fall in net output per worker Y/L unless there are countervailing improvements in knowledge:

E = H (R/L)^ƛ

When natural resources are constant—as they are for the world economy as a whole, although not for individual sub civilizations—this means that the proportional growth rate of the efficiency of labor is:

g = h - ƛn

If we assume that the world economy’s steady-state capital-output ratio is constant across and within eras of economic growth, then the rate of growth of output per worker g_Y/L will be the same as the rate of growth of the efficiency of labor g. We can then read what the proportional rate of growth of knowledge about technology h from the rate of growth of average labor productivity and the rate of growth of the global labor force:

h = g_Y/L + ƛn

I assume ƛ=1/2. Why? If ƛ=0, we are assuming that resource scarcity is simply not a thing: that at a given level of technological knowledge standards of living are independent of how large average firms are and how many workers are drawing on the same metal deposits. If ƛ=1, we are assuming that labor is simply unproductive: that total output depends only on the level of technological knowledge H and the level of natural resources R, with a doubling of the labor force leading to a halving of labor productivity. Both of those are clearly wrong. Halfway between seems to me a not-unreasonable baseline.

Alternative calculations are easy to do if you have a different sense of how important resource scarcity is as a binding or as a not-very-binding constraint on human economies.

There are near-consensus guesses as to the average level of net output per worker and the size of the human population since deep time. Under the further assumption that the effective labor force is a constant share of the human population—that as the share of the population too young to work has fallen, the share that is retired has risen to approximately offset—the rate of labor-force growth is the same as the rate of population growth. And thus I can calculate my guesstimates of the rate of growth of h.

4) The growth and international inequality numbers are very disputable and are often disputed. To gain a sense of what the current semi-consensus is, see: Hans Rosling et al., Gapminder <http://gapminder.org>; Max Roser et al., Our World in Data <http://ourworldindata.org>

5) The source of the idea is, of course, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, London: Communist League, 1848 <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Manifesto.pdf>. My suspicion is that at least in English standard readings of Marx and Engels, at least of the Marx and Engels authorial team in the late 1840s, are not technologically determinist enough. What I see as an assertion in the connotations of the German original of Alles Ständische und Stehende verdampft that it is technology that is doing the work is lost in the traditional English translation “all that is solid melts into air”. Jonathan Sperber suggests “Everything that firmly exists and all the elements of the society of orders evaporate.” That seems to me too passive: steamed away. See Jonathan Sperber, Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life, New York: Liveright, 2013 <http://books.google.com/?id=hBpSh9JYAKcC>.

The underlying ideas, however, are in my opinion best developed by Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity, New York: Verso, 1983 <http://books.google.com/?id=mox1ywiyhtgC>

Also worth reading—certainly a clearer and more organized thinker than Marx, and one about whom I often wonder What kind of thinker would Friedrich Engels have become if he had never met Marx, and thus had not come to regard himself as a mere secretary to the Great Man, is Freddie from Barmen, Friedrich Engels:

6) Friedrich A. von Hayek, “The Pretence of Knowledge”, Nobel Prize Lecture 1974 <https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/1974/hayek/lecture/>

7) Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation, New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1944 <http://books.google.com/?id=IfeMAAAAIAAJ>

8) Takashi Negishi 根岸隆, “Welfare Economics and Existence of an Equilibrium for a Competitive Economy,” Metroeconomica Vol. 12, Issue 2-3 (June), pp. 92-97 <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-999X.1960.tb00275.x>

9) Friedrich A. von Hayek, The Mirage of Social Justice: Law, Legislation, and Liberty Vol. 2, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1976 <http://books.google.com/?id=5Yw9AAAAIAAJ>.

10) Arthur Cecil Pigou, “Welfare and Economic Welfare,” in The Economics of Welfare, London: Routledge, 1920, pp. 3–22 <https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/mono/10.4324/9781351304368-1/welfare-economic-welfare-arthur-cecil-pigou>

11) Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1921, p. 89 <http://books.google.com/id=2yYPeIjgeAcC>; Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984 <http://books.google.com/?id=ajqdpRHpO-oC> wrestles with similar ideas: we cannot think without them—our east-African plains-ape brains are greatly limited—so we must (a) think (b) knowing our thoughts are going awry and thus (c) being always skeptical of what we think we have thought. And if we are lucky, we can occasionally reach a spot at which we can then reflect, and kick away the ladder.

I have also found William Flesch, Comeuppance: Costly Signaling, Altruistic Punishment, and Other Biological Components of Fiction, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007 <http://books.google.com/?id=JSRWPYp1nNUC>, to be very useful.

On “metanarratives”:

Wikipedia: Metanarrative <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metanarrative>: Lyotard highlights the increasing skepticism of the postmodern condition toward the totalizing nature of metanarratives and their reliance on some form of "transcendent and universal truth": “Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodern as incredulity toward metanarratives.... The narrative function is losing its functors, its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal. It is being dispersed in clouds of narrative language…. Where, after the metanarratives, can legitimacy reside?…”

Lyotard and other poststructuralist thinkers (like Foucault) view this as a broadly positive development for a number of reasons. First, attempts to construct grand theories tend to unduly dismiss the naturally existing chaos and disorder of the universe, the power of the individual event. Lyotard proposed that metanarratives should give way to petits récits, or more modest and "localized" narratives, which can ''throw off" the grand narrative by bringing into focus the singular event. Borrowing from the works of Wittgenstein and his theory of the "models of discourse", Lyotard constructs his vision of a progressive politics, grounded in the cohabitation of a whole range of diverse and always locally legitimated language-games.

Postmodernists attempt to replace metanarratives by focusing on specific local contexts as well as on the diversity of human experience. They argue for the existence of a "multiplicity of theoretical standpoints" rather than for grand, all-encompassing theories. According to John Stephens and Robyn McCallum, a metanarrative "is a global or totalizing cultural narrative schema which orders and explains knowledge and experience" – a story about a story, encompassing and explaining other "little stories" within conceptual models that assemble the "little stories" into a whole. Postmodern narratives will often deliberately disturb the formulaic expectations such cultural codes provide, pointing thereby to a possible revision of the social code…

12) Greg Clark, A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007 <http://books.google.com/?id=VKBOmAEACAAJ>.

13) John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy, with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy, London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1873, p. 516 <http://books.google.com/?id=xXU9AAAAYAAJ>

(14) Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward, 2000-1887, Boston: Ticknor, 1888 <http://books.google.com/?id=nRMZAAAAYAAJ>; Edward Bellamy, “How I Came to Write Looking Backward,” The Nationalist (May 1889) <https://www.depauw.edu/sfs/documents/bellamy.htm>.

15) Bellamy, Looking Backward, pp. 152-8.

(16) Oxford Reference: <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/ authority.20110803115009560>

17) His favorite Kant quotation. For example, Isaiah Berlin, “The Pursuit of the Ideal”, Turin: Senator Giovanni Agnelli International Prize Lecture, 1988 <https://isaiah-berlin.wolfson.ox.ac.uk/sites/www3.berlin.wolf.ox.ac.uk/files/2018-09/Bib.196%20%20Pursuit%20of%20the%20Ideal%20by%20Isaiah%20Berlin_1.pdf>. The translation from Immanuel Kant’s 1784 Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Aim is R.G. Collingwood’s, as given in a lecture in 1929. See Henry Hardy, “Editor’s Preface” to Isaiah Berlin, The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Essays in the History of Ideas, London: John Murray, 1990 <http://books.google.com/?id=9LGYQgAACAAJ>.

18) G.W.F. Hegel as quoted by John Ganz, The Politics of Cultural Despair (Apr 20, 2021) <https://johnganz.substack.com/p/the-politics-of-cultural-despair>. @Ronald00Address reports that it is from G.W.F. Hegel, “Letter to [Karl Ludwig von] Knebel”, August 30, 1807. See <https:// www.nexusmods.com/cyberpunk2077/images/15600>. It is quoted in Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History, 1940, translated by Dennis Richmond <https://web.archive.org/web/ 20120710213703/http://members.efn.org/~dredmond/Theses_on_History.PDF>

19) Madeleine Albright, Fascism: A Warning, New York: HarperCollins, 2018 <http://books.google.com/?id=Zzs2DwAAQBAJ>.

20) Fred Block: “Introduction” to Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation, Boston: Beacon Press, 2001 [1944], pp. <https://github.com/braddelong/public-files/blob/master/readings/block-intro-polanyi.pdf>

21) See Charles I. Jones, “Paul Romer: Ideas, Nonrivalry, and Endogenous Growth,” Scandinavian Journal of Economics Vol. 121 No. 3, 2019, pp. 859–883 <https://web.stanford.edu/~chadj/ RomerNobel.pdf> Where does the ½ come from? It is a hopeful guess: a judgment that natural resources are, in the average and over time, roughly half as important as human brains, eyes, hands, and muscles in boosting production. It cannot be 1% for 1%: that would mean that individual human eyes and hands and brains are powerless in adding to production, and only resources plus the gestalt of total human knowledge matter. It cannot be 0% for 1%: that would mean that resources and resource scarcities do not matter at all. 0.5% for 1% is simply halfway in between.

22) Clark, Farewell, pp. 91-6.

23) Simon Kuznets, Modern Economic Growth: Rate, Structure, and Spread, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966 <https://archive.org/details/moderneconomicgr0000kuzn>.

24) Edward Shorter and Lawrence Shorter, A History of Women’s Bodies, New York: Basic Books, 1982 <https:/books.google.com/?id=iAzbAAAAMAAJ >. Consider that one-in-seven of the Queens and Heiresses Apparent of England between William I of Normandy and Victoria of Hanover died in childbed.

25) Mill, Principles, p. 516.

26) Note that there are powerful and very critical implications here for the position of Isaiah Berlin. Berlin drew a firm distinction between the “negative liberty” that he traced to John Stuart Mill and company, and that he broadly saw as good, and a “positive liberty” tradition that he saw as much more dangerous. See Isaiah Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty”, Oxford: Clarendon, 1958 <http://cactus.dixie.edu/green/B_Readings/I_Berlin%20Two%20Concpets%20of%20Liberty.pdf>. But Mill did not buy the pig-in-a-poke that claims a substantial difference between whether if locked in a cage (a) there is no key or, alternatively, (b) you just cannot afford to buy the key. Strong advocates of negative liberty as the true liberty do draw such a strong distinction.

27) William Stanley Jevons, The Coal Question: An Enquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal-Mines, London: Macmillan, 1865 <http://books.google.com/id=ww88bypTQUEC>

28) Marx and Engels, Manifesto, p. 17.

29) Friedrich Engels, “Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy”, Paris: German-French Yearbook, 1844 <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/df-jahrbucher/outlines.htm>, not paginated.

30) Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program, London: 1875 <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/>, n.p.

31) Richard Easterlin, Growth Triumphant: The Twenty-first Century in Historical Perspective, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2009, p. 154 <http://books.google.com/?id=wpRFDwAAQBAJ>

32) Thomas Robert Malthus, First Essay on Population, London: Macmillan, 1926 [1798] <https://archive.org/details/b31355250>; the phrase “Malthus had disclosed a Devil” is from John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, London: Macmillan, 1919, p. 8 <http://books.google.com/?id=cQ8-AQAAMAAJ>.

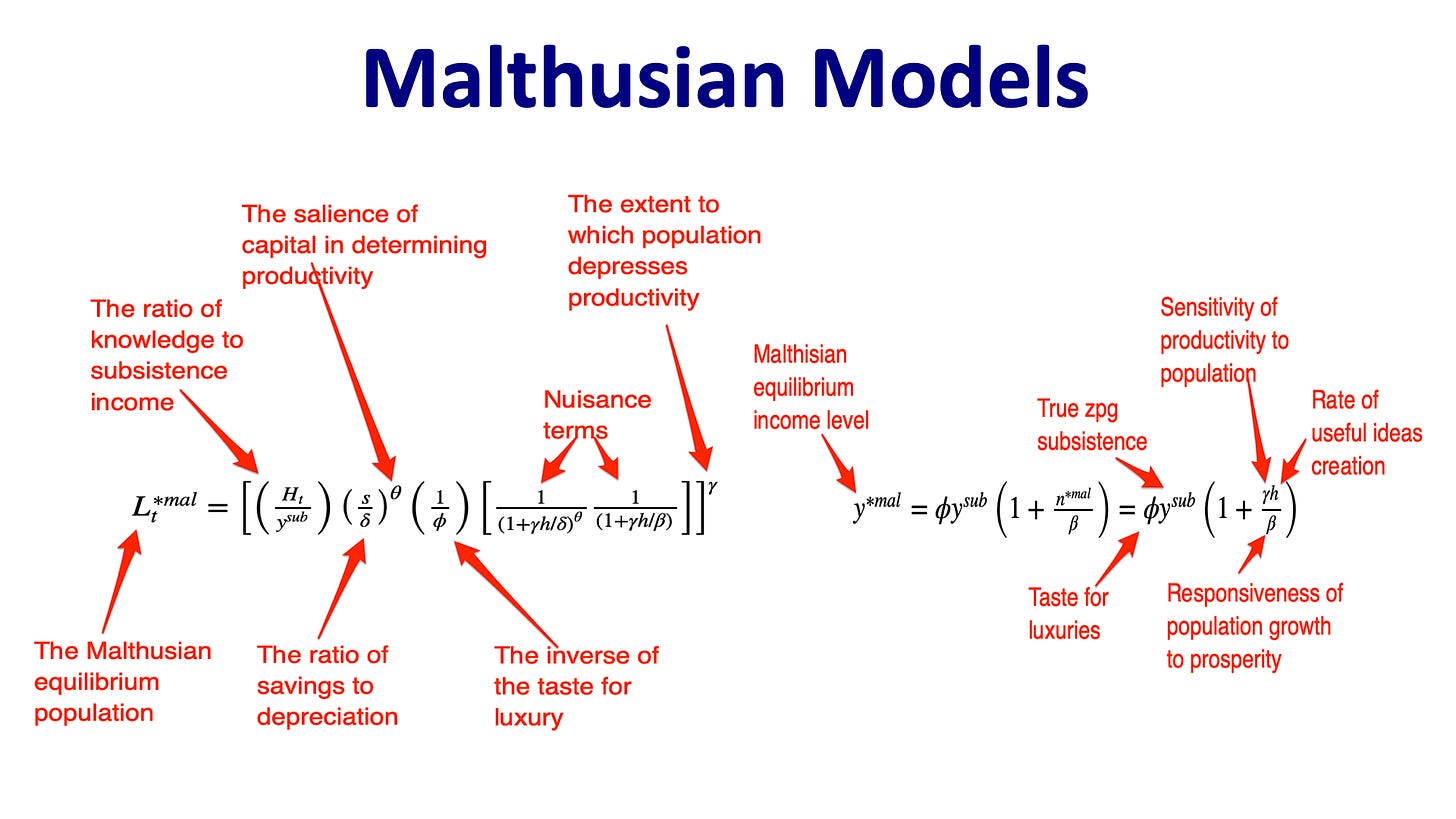

In What Sense Was the Pre-Industrial Economy “Malthusian”? Let me try to explain in what sense I think that pre-1500 Agrarian-Age (and 1500-1770 Imperial-Commercial Age, and 1770-1970 Industrial-Revolution Age, in fact all pre-demographic transition economies) were Malthusian.

The problem is that I want to start from a basecamp: the Solow-Malthus economic-growth model. So I send you off to read my background theory lecture notes on the Solow-Malthus economic-growth model:

Back? Angry that I made you march through 14 pages of algebra? Contemptuous that we economists’ inclination to use math serves as an entry barrier meaning that we only have to talk to ourselves, and not to people trained in other disciplines who are unable or unwilling to follow what happens when you start taking the derivative of a logarithm?

Sorry: then I really cannot help you.

But if you are merely annoyed because you refused to be marched through 14 pages of algebra? If you are willing to take what I have to say about Solow-Malthus economic-growth theory provisionally on faith if only I give you a quick precis to get you to the bottom line?

Then I can help you. Here we go:

If we are willing to assume that:

A society’s productivity depends primarily on (a) its willingness to save and invest, and (b) the efficiency of its workers, which is in turn a function of (c) its level of technology—its useful ideas about manipulating nature and organizing humans—and (d) its natural resources per worker.

A society’s population growth rate depends on (a) its level of consumption of necessities that make you biologically fit to reproduce relative to (b) its sociologically-determined familial and other institutions that potentially curb the rate of reproduction.

Societies differ in the proportion of their productive resources they allocate to necessities vis-à-vis luxuries.

Technological progress before the Industrial-Revolution Age proceeded at a slow average proportional growth rate h measured in hundredths of a percent per year.

Then we get:

The right-hand side of the slide above: the society’s level of productivity per worker will head for and then tend to oscillate around a Malthusian level equal to (a) the society’s taste for non-necessities (which include such things as having a rapacious and greedy upper class, and liking to live in cities), times (b) its sociologically-determined subsistence level of necessities consumption (which can be raised by things like a late age of first female marriage, large-scale female infanticide, or frequent chevauchées), times quantitatively unimportant nuisance terms.

The left-hand side of the slide above: the society’s population density will head for and then tend to oscillate around a Malthusian level equal to (a) the quality and abundance of natural resources per acre, times (b) the ratio of the technology level to the “subsistence” level of necessities consumption at which the population barely replaces itself, times (c) the propensity to save and invest in everything that makes humanity more productive (from tools to liming the soil to building commercial networks), (d) a chief boost to which its the provision of a pax imperia, times (e) the inverse of the taste for non-necessities, all (e) raised to the power that is the extent that higher population induces resource scarcity and thus lower productivity, times quantitatively unimportant nuisance terms.

As the centuries and millennia pass, the Malthusian equilibrium level of population density will slowly rise as technology improves.

And as the centuries and millennia pass, the Malthusian level of typical human living standards will slowly rise even as necessities-valued production per worker does not to the extent that there is faster technological progress in making middle-class conveniences than in making true bioreproductive necessities.

But even though a society tends to go back to its Malthusian equilibrium, it does not have to be there: all kinds of shocks can knock it away.

Moreover, and more important, the Malthusian equilibrium can and does shift. There are BigTime changes across societies and over time as polity and sociology shift in:

the subsistence level of necessities consumption

the taste for luxuries

the incentives to save and invest

These drive big differences in how societies look and are, and big differences in how societies’ economies grow and shrink: truly dire Dark Ages like post-Roman Britain or the early-Iron Age Ægean; truly magnificent (if often cruel and astonishingly unequal) civilizational “efflorescences” as Jack Goldstone has taught us to call them. Establish a pax imperia, with associated protection of commerce and industry from freelance expropriation by thugs with spears through a government that controls its own functionaries and so generate lots of savings, investment, and an increased division of labor; acquire a taste for luxuries, especially living in cities and upper-class and even middle-class display of comfort; and generate sociological institutions that curb and control female fertility and female-child survival, and watch what happens. On the other side, have barbarians within the gate so that as much wealth as possible is immediately turned into silver and buried, establish a sociology of very early female first marriage, and have little taste for or indeed specialization in producing non-necessities—and your Malthusian equilibrium can shift to something of interest to archæologists, but not of interest to artists or indeed to connoisseurs of material culture.

Moreover, remember this always: the gulf between the standard of living of the upper and even the middle class (who leave the major archæological footprint) on the one hand and the peasant-craftsman-servant working class on the other, whose reproduction generates the resource scarcity that anchors the Malthusian equilibrium—that can and does vary widely and wildly as well.

That pre-Industrial Revolution Age history was “Malthusian” does not mean that nothing interesting happened, or that everything was the same.