LECTURE NOTES: 5.4. Post-2010 "Polycrisis": Culture, Communications, Politics, & War

Rough but edited (and significantly expanded) lecture transcript. Part of Econ 135: The History of Economic Growth Course Unit 5. After Neoliberalism Comes "Polycrisis": extra-economic dimensions...

Rough but edited (and significantly expanded) lecture transcript. Part of Econ 135: The History of Economic Growth Course Unit 5. After Neoliberalism Comes "Polycrisis": extra-economic dimensions of our polycrisis...

A true behemoth of a lecture, in this form at least…

5. After Neoliberalism Comes “Polycrisis”:

Global Warming

Neoliberalism & After

Post-2010 “Polycrisis”: Economics

Post-2010 “Polycrisis”: Culture, Communications, Politics, & War

The Renewed Fight Over Systems & Orders

5.4.1. Class Intro: Where We Are & Where We Are Going:

Wow: the semester has only five classes remaining.

The current unit is Unit 5: "After Neoliberalism". That means: current events.

We started Unit 5 with 5.1. Global Warming. We then in 5.2. Neoliberalism & After examined some of the features that led to major discontent with the Neoliberal Order—discontent that has everyone believing that the Neoliberal Order is toast and done, although nobody has a sense of what will be the hegemonic pattern for organizing our economies and directing our political economy in the future. Hence the large number of people resorting to the famous quote from pre-WWII Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci: “The Old Order is dying; the new appears perhaps stillborn: now is a time of monsters".

Most recently in 5.3. Post-2010 “Polycrisis”: Economics we took a look at the economic aspects of what Columbia historian Adam Tooze has taught us to call the "polycrisis". Now in 5.4. Post-2010 “Polycrisis”: Culture, Communications, Politics, & War we will quickly cover the cultural, communicative, political, and military dimensions of the polycrisis. And then in 5.5. The Renewed Fight Over Systems & Orders we will discuss the renewed debate over economic and political orders and systems that we are having in this current interregnum, after the fall of the Neoliberal Order, and before whatever comes next, in the context of what appears to be a shift from the age of the Globalized Value-Chain Economy to an age which may be one of the Attention Info-Bio Tech Economy—and will be the age of Global Warming.

That will bring this Unit 5 to a close.

Then, when we reconvene, we will project into the future: Unit 6: Conclusion starts with 6.1. The History of the Future[?], before finishing with 6.2. Pulling It All Together and 6.3. Conclusion & Review.

5.4.2. Previewing “5.5. The Renewed Fight Over Systems & Orders”:

Let me try to, briefly, telegraph what questions we are going to not answer but pose when we reach the end of this Unit 5:

There is now on issues of economic organization and political economy no clear central position, call it “hegemonic”, in the sense that such a position is the boss in that it sets the agenda and everyone else, especially those who disagree, has to deal with and react to it. There is right now no analogue to the 1933 to 1980 Social-Democratic Mass-Production New Deal Order. There is right now no analogue to the 1980 to 2010 Globalized Value-Chain Neoliberal Order on how things should be moving forward. We are thus in a similar interregnum situation to after World War I—the interregnum after the Belle Époque of the SteamPower-Society Pseudo-Classical Semi-Liberal Order of things, and before the Mass-Production Social-Democratic New Deal Order.

1870 to 1914 Belle Époque-era Pseudo-Classical Semi-Liberalism was pseudo-classical because rather than being time-honored it was brand new. 1870 to 1914 Belle Époque-era Pseudo-Classical Semi-Liberalism was only semi-liberal because it both retained and gloried in a great deal of not freedom but hierarchical and cultural subordination, and because a great deal of its point was to use the mechanism of property and its grossly unequal distribution meld together an economic upper class of entrepreneurship and industry from the coming of explosive Schumpeterian creative-destruction Modern Economic Growth with the political-social upper class of landlords and functionaries that SteamPower Society had inherited from the past of human Societies of Domination.

This Belle Époque Order was shattered by the cataclysmic events of World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II. Many wanted to rebuild it. They failed. Instead, there was an interregnum—an at least five-cornered fight over how to organize the economy and society between those who wanted to restore the Belle Époque Order; those who wanted to become even more authoritarian and reactionary with rule by king, nobles, churchmen, and soldiers; Lenin’s (and later Stalin’s) Communists; the Fascists; and those desperately seeking for some Fifth Way through. Were the Communists “the future… and it works”? Were the Fascists right that people were not fundamentally rootless consuming animals seeking as individuals the mere prosperity of utilitarian pleasure, but rather beings deeply rooted in the collectivity that was a nation and that nations needed a Leader to tell people what the goals of the nation were and to carry the nation forward to accomplish those goals? That the Belle Époque Order had failed and led to the cretinism of parliaments because it tried to construct politics from the bottom-up out of human desires for prosperity and peace, rather than top-down from some Maximum Leader’s desire for Glorious Purpose? Enormous chaos. Interregnum. Competing visions for the future economic and political order clashed, disastrously. And more than 100 million people died of violence and starvation.

And yet we found a way through. The interregnum came to an end. In the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt became president in a “throw the bastards out” reaction to the inability of the center-right semi-progressive Herbert Hoover administration to do anything to combat the Great Depression. Roosevelt, on the other hand, was going to try everything possible and many things impossible—and then try to jduge and reinforce success. Non-ideological—or rather multi-ideological and incoherent—at the start, the things that Roosevelt judged successful cohered in and became an ideology that then became the New Deal Order.

This Social-Democratic New Deal Order in the context of the emerging Mass-Production Economy worked.

Spread over the Global North via U.S. victory in World War II and the coming of the Cold War, it promoted rapid and remarkably equal economic growth at a pace previously unseen in world history over the years from 1933 to 1980. Big Government: ensuring high employment levels and job availability for most citizens while redistributing income and providing public goods and services. Big Labor: Counterbalance the power of Big Business to create channels for upward mobility and prosperity for those without the great advantage of having chosen the right parents. Big Business: leveraging the economies of scale enabled by mass production to generate unprecedented wealth. Not only was economic growth supremely rapid, not only were the inequities in its distribution much less than in the Belle Époque Order, but you could be pretty confident that something in at least one of those three sets of large bureaucratic institutions would have your back. And if none did? New Deal Order society was open enough that you could ORGANIZE! And you could win something. For many it was Big Social Movement that had their back: civil rights, feminism, environmentalism, and so on.

But then the New Deal Order collapsed in the 1970s. The Neoliberal Order quickly rose in its place. It saw Big Government and indeed all of the New Deal Order “Bigs” as too bureaucratic and too constraining of freedom. Neoliberal ideology called for a reduced role of government, promoting free-market capitalism and people’s individual powers to do their own thing with their body, their life, and their property. But was the Neoliberal Order successful? Not in the Global North, I argued, for it had only one real accomplishment: making income and wealth inequality much greater. Right-neoliberals saw this as a feature: Making the non-rich poorer and less well-supported by Big Government would incentivize them to be more hardworking and responsible, while making the rich richer would motivate them to be more entrepreneurial and investing and hence boost economic growth, plus the resulting more unequal distribution of wealth would be more fair by providing a more just allocation of the good things to those who deserved them.

The hegemonic authority of the Neoliberal Order had more or less completely collapsed starting by 2010, in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis and the subsequent Great Recession and Anæmic Recovery. Hence we are now in a new interregnum, with history not repeating the 1920s and 1930s in this respect but yet rhyming. We do not know how this interregnum will end, but at least we can view the game board and tag some of the pieces on it, and so at least partially assess possibilities.

5.4.3. Hammering Home the Importance of Ongoing Global Warming:

We started this Unit 5 looking at Global Warming. Global Warming is, I think, the biggest thing likely to make global economic history in this era After Neoliberalism play itself in a significantly different key than during the Modern Economic Growth era of the Belle Époque, interregnum, New Deal, and Neoliberal Orders from 1870 to 2010. Dealing with Global Warming is likely to be extremely costly, eating up a substantial chunk of our potential wealth. In the Modern Economic Growth era humanity as an anthology intelligence had a difficult time struggling with adjusting society’s organizations and practices to the waves of Schumpeterian creative-destruction driven by the underlying dynamic of technology-fueled growth and transformation. And this was with the support of the availability of a substantial technological dividend to help ease transitions, either by supporting big losers from the Schumpeterian dynamic to make them little losers or by assembling coalitions to make the big losers sit down and shut up. With global warming absorbing a potentially large share of what would otherwise be our free technological dividend over the next fifty years, humanity’s ability to manage is likely to be substantially reduced. Along this dimension, in the Global Warming years we will face a more difficult time than people did in the 1870 to 2010 Modern Economic Growth years.

That, in a nutshell, is why I brought my book Slouching Towards Utopia to an end in 2010. I wrote that history after 2010 is likely to have a different Grand Narrative than the one of extraordinarily increasing wealth, Schumpeterian creative-destruction, and humanity’s attempts to manage the mishegas that was my main thread and through-line in telling the story of 1870 to 2010.

Now Larry Summers, an optimist, someone with whom one disagrees only at one’s grave intellectual peril, believes that I am wrong: that I should have ended Slouching Towards Utopia with “the story continues…” and that the proper Grand Narrative to understand our present and future is largely the same as the one I set out to try to understand the main points of the 1870 to 2010 past. He points to the extraordinary revolutions in solar-power technology as merely one of the reasons for optimism. I am not yet as optimistic as Summers. But I hope he is right.

Neoliberalism is a belief system that emphasizes trust in the free market, a desire for reduced bureaucracy, and the idea that people should be able to exercise their social power through private property ownership. This property can then be used in the market to accumulate wealth, and in society to shape one's identity and lifestyle. Neoliberalism extends beyond just wealth and contractual rights. It also encompasses things like the quality of one's neighborhood and the desire to prevent certain types of development, such as apartment buildings, from being built nearby. These localized property interests are considered part of the broader neoliberal order.

5.4.4. What Was Wrong with the Neoliberal Order?

Many things. There was a lot of economic mismanagement, most of it driven by the ideology that government action is guilty and cannot be demonstrated innocent. There was the exaltation of property rights as the only rights that society should vindicate, in spite of people’s rock-solid conviction that they have other rights than property rights that are even more important. The denigration of a government that regulated industry to constrain spilled over into a denigration of government that tried to do anything that might run into opposition, in the form of somebody with social power who thought that their property interests would be impaired. The NIMBYism we have seen—that we see all around us right here in Berkeley, where people with very valuable close-in suburban homes indeed are desperate to keep what they see as their style of life and fear will be their property values from being adversely impacted by anyone who builds an apartment building on the next block—is a powerful part of the Neoliberal Order. The result? People who ought to live in Berkeley apartments live, instead, in Tracy, out beyond the Altamont Pass.

Plus trust in the market and distrust in the government means you cannot even think of what to do if world market tides are not flowing your way. Plus there were no alternative institutions to the New Deal Order’s Big Government, Big Business, and Big Labor that you could count on to have your back—and promises that Big Bureaucracy would be effectively curbed and that Big Market would offer you a realm of freedom and of rapid income growth were lies for all except the Top 1% winners from the Neoliberal Order.

Plus the Neoliberal Order produced fear: fear that there was no strong-enough social safety net coming from government or elsewhere in place to support you. Right-Neoliberals, remember, viewed this as an asset: people would be forced to stay focused and become self-reliant. But the principal consequence was that, father than optimism that change would bring a future would be better, the vibe became worries that changes in technology, economics, politics, and finance could take away what little people currently had: protect your current assets which are under threat from the strange and new, in the form of people, trends, and technologies. What had been a vibe that the future was one of opportunities to grab to improve your life died away.

This had, I think, dire and destructive consequences for the collective mind of the American Republican Party. The Neoliberal Era saw it under go a profound transformation. Historically, the party was for people who were millionaires—either present secure millionaires, temporarily embarrassed millionaires, or people who were going to become millionaires. People who believed that technological and economic changes would benefit them as they seized the new opportunities change opened up. People of entrepreneurship, benefiting from business, enterprising and able. But today’s Republican Party is very different. It is of people scared of losing what they have, from those with small amounts of equity in their homes who fear cat-eating immigrants will move next door to teh shareholders of Koch Industries who see themselves as owning not an energy company that can profit immensely from the technological change that the solar-power will bring but as parasitic owners of oil-in-the-ground for whom any change is a major loss, therefore they try to keep things as they are even if “as they are” includes cooking the planet.

This shift in the mind of the Republican Party away from being the part of enterprise and opportunity is a huge problem for today’s United States.

5.4.5. Polycrisis: The Economic Side:

The fall of the Neoliberal Order brings our interregnum. Alongside this political-economic event is the continuation of technological progress and Schumpeterian creative-destruction: we are transitioning away from the economy of the Globalized Value-Chain to something else, which might or might not be an Attention Info-Bio Tech mode of production. This underlies our polycrisis. Key aspects include: hyperfinancialization leading to a sharp disjunction between what leads to profit and what leads to production; hyperglobalization and a sharp increase in fragility and risk; hyperdigitization and a sharp narrowing of upward mobility pathways to opportunity and prosperity, with a focus on élite educational attainment as nearly the only route to even a little social power, prosperity, and self-determination; and then there is what I am calling “techno-feudalism”.

I do not like that word. I do not have a better one. It gestures toward growing segments of the economy, the culture, and the infosphere focused on the capturing of your attention and its subsequent sale to those who do not have your best interests in mind—to those who want to sell you things you will regret buying and to provide you with experiences that do not enlighten and entertain but instead misinform, depress, and scare you.

Proposed ways of dealing with the economic side of our polycrisis are, on the one hand, policies that are place-based to produce prosperity where people are (since in a NIMBY world we can no longer rely on people being able to move to opportunity) and policies explicitly focused on industrial development to stem adverse global-market tides; and, on the other hand, a strongman to overcome an ossified system that generates fear and to protect people from the enemies that they fear will take what property they have.

But there is much more to the polycrisis than just the economic side.

5.4.6. Polycrisis: The Cultural Side:

I have always had a hard time taking “cultural panic” seriously. It sounds to me like something we have been hearing for the last two-thousand years, and for the two-thousand years before that. There are always grumpy old men yelling at the clouds about how things today are worse than the old days when children respected their parents and when—as the oligarchs of the late Roman Republic put it—as was proper, a sword cost more than a pretty-boy slave, and a farm cost more than an imported jar of fish sauce made on the northern shore of the Black Sea. Grumpy old men yelling at clouds seems a constant in human society. With an again society, we have more old men to be grumpy.

The experience that reinforced my own grumpiness with respect to “cultural panic” came back in 1996, as I was watching the senator from Kansas and Republican Party presidential candidate Bob Dole. Dole was not my favorite person by far. But he was not conspicuously crazy or mean—he genuinely wanted to do what was best for Kansas and the United States. During his campaign, Dole would occasionally reminisce and ramble about how America had been better in the past, and how he was going to build a bridge back to that better America—say, the America of 1940.

America had not been better in 1940 than it was in 1996. You can count the ways.

But in 1940 the seventeen year-old Robert Dole was young and strong and healthy in Russell Kansas. In April 1945—three weeks before Nazi Germany surrendered—Second Lieutenant Robert Dole of the US 10th Mountain Division was hit by Nazi machine-gun fire while leading a foot assault high in the Italian Apennine Mountains near Castel d'Aiano. Dole's right shoulder was shattered, and his arm was rendered permanently unusable. His collarbone and vertebrae were also fractured. The injury caused severe nerve damage, leading to partial paralysis. He nearly died from blood clots and a severe infection following his injuries. Dole spent nearly three years in recovery and rehabilitation, undergoing multiple surgeries and intensive therapy. He permanently lost the use of his right hand and arm. He regained limited use of his left hand. And for the rest of his life, on awakening one of his first thoughts was: “this hurts; a lot”.

Dole really did not to be fuzzy, numbed with opiates. He wanted to do his job. He is an extreme version of the human memory of how one used to be young, strong, and healthy and so things must have been better in the old days. As I approach 65 I understand his perspective more and more. And someday I may say that things were better back in 1982—but they were so only for me as I live in my body, and only to a very limited degree even so.

But I may be wrong in my strong tendency to dismiss “cultural panic”:

Cultural aspects of polycrisis may be, this time, much more of a real thing than the usual cultural panic.

Consider the poorest 10% of young men in America. What are they doing? They are not attending school or holding steady jobs. They are also not caring for children or elderly relatives. They do not receive substantial public support: the Earned Income Tax Credit is available only to those who work, and is tiny unless you have children; the desiccated bones of what was once welfare—Temporary Assistance for Needy Families—is also only available, when it is available, flor those caring for children. So how are they living? And on whose dime?

Consider the relationship between genders. It has been undergoing a significant renegotiation since the start of Modern Economic Growth and the Demographic Transition and the beginning of the drop of pregnancies per potential mother from nine to two. What will and what should gender roles and expectations now be in our new world? The renegotiation continues. How well is it going? There is certainly a perceived shortage of “marriagable men” these days.

In the old days mammalian biology and patriarchal men taking advantage trapped the majority of women into roles that kept them largely confined to an inward-facing household-centric sphere, with men out in the world regarding women as sources of haven after the outside work was done, and perhaps as icons on pedestals, or shining guiding stars. As fantasy author J.R.R. Tolkien, living fairly early in this transition, noted: that was not at all adequate. A wife was not a shining, guiding star, but rather your “essential companion in shipwreck”. And I attribute the existence of Edith Bratt to Tolkien’s remaining sane after a World War I that saw all but one of his close friends dead—if, indeed, Tolkien was sane. Do note that in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings the women are not passive and home-bound, but seriously BADASS: Galadriel and Eowen; and in his other stories we have Luthien, and Elwing transformed into a seagull and bearing the silmaril jewel of Beren and Luthien reaching her husband Eärendil on his ship and them together using the jewel to pierce the Shadowy Seas and make their impossible voyage.

Last, loss of privilege—racial/ethnic, physical, linguistic, geographic, and gender-based—is a thing. Such privilege becomes more important in cementing one's social status and confidence in the context of slow overall income growth. The productivity slowdown of the 1970s, and subsequent failures to restore rapid economic growth (aside from the 1994-2000 Clinton administration), have made it difficult for people to think that their greater wealth in some way compensates for status lower in some dimensions.

There is a cultural element to our polycrisis—but its importance and what likely paths there are for its resolution are subjects that elude me.

5.4.7. Polycrisis: Communication & Public Reason:

Communication is critical for humanity as an anthology intelligence. Our modes of being not only encompasses how we work and produce and how we distribute resources, but also how and what we communicate, and then have our individual thinking shaped by communication.

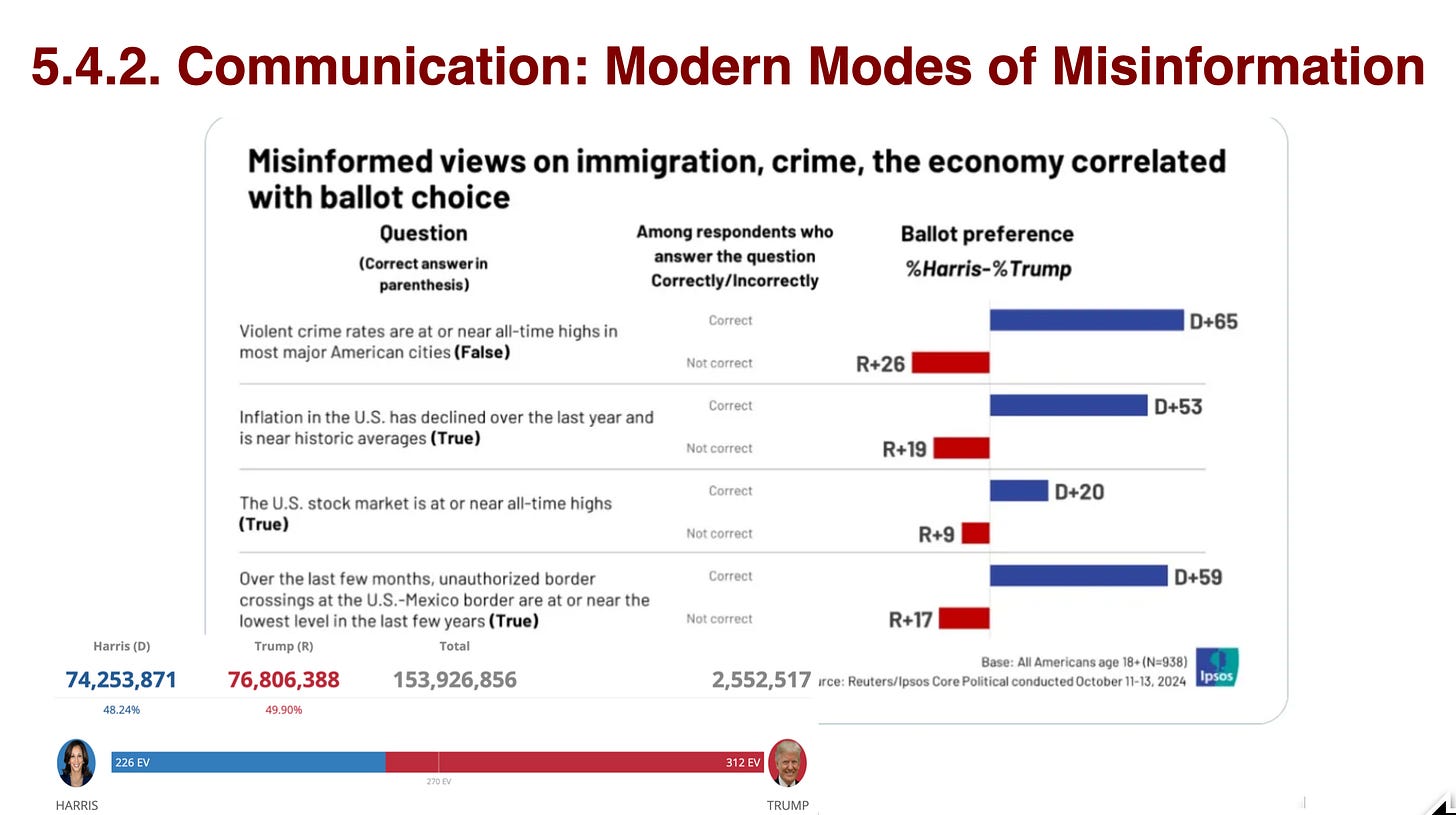

The ease of spreading misinformation and the growing incentives to do so are things. Even when the goal is simply to scare people and keep their attention glued to the screen so their eyeballs can be sold to advertisers, the consequences can be dire. The social media ads that I see are truly bizarre surprisingly often—with fake diabetes cures and cryptocurrency token grifts only the tip of the iceberg.

The Reuters/Ipsos Core Political Survey conducted a poll in mid-October 2024, a month before the election. It asked about violent crime rates in American cities. Violent crime rates are not at or near all-time highs. They are about the same as they were in the 2010s, and perhaps 1/3 of what they were in the 1970s and 1980s. Yet many believed crime rates were at or near all-time highs. They supported Trump 26%-poin margin. Those better informed about the actual crime statistics, by contrast, broke for Harris by a 65%-point margin.

The United States achieved its “soft landing” with respect to inflation some 18 months ago. The inflation problem caused by the plague and the rapid-recovery aftermath has been resolved, or, rather, mostly resolved itself. It is no longer a significant issue. Yes, overall prices are about 20% higher because of the inflation episodes, but so are incomes. And no big redistributions of wealth were generated by the process. The key and salient indicator of gasoline prices has returned to its pre-plague levels. Those who undersood that the inflation rate has fallen back to near-normal supported Harris by a margin of 53%-points. Those who believed inflation remained high broke for Trump by a 19%-point margin.

The stock market is a key indicator. The American media report on it multiple times a day. They have decided it is the summary scoreboard for the economy as a whole—god alone knows why. Over the past nine months, the stock market has reached an all-time high on about one out of every four days. Near ubiquitous coverage of the stock market's performance should makes it difficult to avoid being aware of this. Those who had listened and remembered at least once broke for Harris by a margin of 20%-points. Those who were misinformed went for Trump by a 9%-margin. informed about the market's sustained strength tended to vote Democratic, while those less aware of the market's performance were more likely to support Trump.

The stock market is a key indicator that the American media frequently reports on, often multiple times a day. Over the past nine months, the stock market has reached an all-time high on one out of every four days. It fluctuates, with some days seeing higher levels than others, but a significant portion of the time, it is setting new record highs. This ubiquitous coverage of the stock market's performance makes it difficult to avoid being aware of its status. Those who were more informed about the market's sustained strength tended to vote Democratic, while those less aware of the market's performance were more likely to support Trump.

And then there is the border: those who knew that unauthorized border crossings were at a low relative to the past few years gave a 59%-point edge to Harris, while those who thought that claim was false gave a 17%-point edge to Trump.

The recent election was extremely close. The margin between the candidates was very narrow. The last vote totals I saw showed Kamala Harris with 48.24% of the vote and Donald Trump with 49.9%, and the slower arrival of the vote count from the Pacific Ocean states means that that margin is going to shrink further. In such a close vote, each small factor made the decisive difference. But misinformation and its correlation with voting intentions is not a small but rather a very big factor.

It may be that beliefs about the world shape who people decide to vote for. But it also may be that people hold beliefs because of who they have already decided to vote for. If the second is the case—if people decided to vote for Donald Trump because they liked his presentation-of-self on The Apprentice and since as a real asshole, and concluded that he would as president be mean to people and they liked that—then the present and future of the United States and indeed of the world is very depressing indeed.

But I think that is unlikely. I think people voted for Donald Trump because they believed what Fox News and others of that ilk put in front of their eyes on their screens. They knew that their one's own neighborhood and personal circumstances were relatively good, with low crime rates, gas prices at normal, and their incomes having kept pace with inflation. But they were shown that a lot of people were struggling, that the system was broken, and that we needed to do something to shake government into a better configuration—and the driving asshole boss that the Reality TV film editors on The Apprentice created out of a mass of low-quality footage appeared to be what America needed. Voting for change, not out of personal necessity but out of concern for the greater good, demonstrates a commendable civic-minded perspective focused on solving societal challenges, rather than just focusing on one's own immediate situation that case, the state of the American voter is good. What is bad is the communications system underpinning public reason that creates such enormous misinformation even though it conflicts with the evidence of what people see about their situations and their neighborhoods. And what is bad is that people seem to believe that Reality TV is, well, real—rather than what it is: a boiling down of 20 hours of footage to a one-hour episode to produce an arresting story and characters that are profoundly fake.

We need to evaluate our communication methods and how effectively they are serving us at the moment. Two historical analogies that we have seen before in this course come to mind. They may be useful in this assessment:

One historical analogy: The invention of the printing press in the 1450s was a pivotal, Gutenberg Moment. This technological advancement made books and printed materials significantly cheaper and more abundant by a factor of 20 or so. This had a profound impact on the dissemination of knowledge, as it allowed for the rapid circulation of information. The increased accessibility of knowledge facilitated the development of modern science. Scholars were now able to gather and compare multiple sources of information, enabling them to challenge and refine existing theories—noting, for example, how there were a lot of strangely parallel anomalies in the geocentric Ptolemaic model which could all be explained with a heliocentric approach, thus enlisting Occam’s Razor on the side of Copernicus. Printing drove a good deal of economic growth in west-European cities.

Culture flourished. Cognitive individualism rose as people could now have more than one book, could clearly see how often authorities disagreed, and recognize that they must make their own judgments. Governments acquired the potential to be more than just predatory entities. The creation of a public sphere for speech and debate forced politics to respond more to the concerns of the people.

But printing also brought the Reformation—the splitting of the Christian church in Western Europe into Catholic and Protestant factions, with new and different ways of thinking about God. I have no stomach for the fundamentalist Protestant views of the writer's ancestors, those who shot out the stained glass windows of Canterbury Cathedral for target practice. And I have no stomach for western and central Europe’s two centuries of near-genocidal religious war.

The Gutenberg Moment enabling the mass dissemination of information was Janus-faced, at least until sociology changed to catch up with information-dissemination technology.

A second historical analogy: The coming of mass media—first newspapers and then radio, at the same time as the coming of Modern Economic Growth was a further step-change in the cost and pace of communication. Politics could shift from being a network-based, top-down process to one subject to a more direct form of mass mobilization. Instead of decisions flowing down through layers of personal connections, mass media allowed politicians and others to speak directly to large public audiences. Increased political mobilization on a wide range of issues had effects both positive and negative as it transformed the nature of the political process.

William Randolph Hearst wanted the United States to go to war with Spain and conquer Cuba. Hearst sent reporter Frederick Remington to Cuba to take pictures of Spanish atrocities and the start of the warto justify US intervention. The almost surely false but still thought-provoking story story goes like this: Remington telegraphed Hearst saying, "Everything is quiet. There is no trouble here. There will be no war. I wish to return." The story is apocryphal, the Hearst papers’ attempts to mobilize the US for war is historical, as is their success.

If you want to explore this topic further, there are experts in media studies and information science who would be better guides for you than me. What I can do provide a reading list of relevant resources I have found helpful in thinking about the fact that we have new and different modes of communication that seem to work very hard to create mis informed voters. Read Benedict Anderson, Alan Brinkley, Elizabeth Eisenstein, Ernest Gellner, and Marshall McLuhan; watch Lein Reifenstahl; and also read the Frankfurt School trio of Neumann, Marcuse, and Kirchheimer.

5.4.8. Polycrisis: Nation-Level Politics:

People can feel scared at the prospect of change when there is a lot of it, and it doesn't seem to be clearly for the better. This creates a "politics of fear". Such a thing can go in either of two directions.

One direction it can go is the way that my sometime teacher Judith Nisse Shklar emphasized: change and fear can create a liberalism of fear. People need security so that they do not need to be afraid, and that security is built out of society’s institutions and practices. We may agree on little else, but we can agree that we all would be less fearful and more happy if we did not lie awake worrying that some Stalin will decide that we are a problem, and then tell one of his underlings “no person, no problem”; that the secret police will knock on the door and drag us off to a concentration camp; that the resources that we thought were our on which we were going to build our material life are no longer ours because some bureaucrat in somebody’s pay has said so via a process from which there is no appeal. We may not like the way many of our peers pursue happiness. But perhaps we can agree that we do not like a world in which the only people who can pursue happiness are those for whom society vindicates their rights to life, liberty, and property because politics has tossed them to an insecure position high on society’s pyramid. Perhaps we can agree that we all would like a society in which each of us has our natural rights to life, liberty, and property vindicated so we can pursue our happiness, even if we then have to avert our eyes and try not to think of the bad ways in which other people are doing so. Curb fear and domination via creating a realm of freedom, and giving everyone at least some societal power to block the destruction of their life on the one hand and also to do things on the other.

Indeed, Judith Nisse Shklar saw this liberalism of fear as pretty much the only basic foundation on which, historically, stable, free societies had ever been built.

But it can go another way. People can reject the idea of putting trust in institutions and practices. People can insist on putting trust in people, in leaders, who then promise to keep them safe from fear. Fearful people are prone to seek refuge in Strongman politics. Seek out a strong, authoritative figure who shares your enemies to protect you. Rely on him to beat up people who would threaten you. The money-lender has charged you a usurious interest rate? Seek a Strongman who will cancel the debts. It has gone beyond that and a court has enslaved you to him for ten years? Seek a Strongman who will abolish the institution of debt slavery. The oligarchs and the clan heads have engrossed all the good agricultural land? Seek a Strongman who will redistribute it so that everyone has fair chance

As we saw now long ago, such were the strongmen, the “tyrants”, the tyrannoi of late-Archaic early-Classical Hellenic civilization. It has gone beyond that an has gone beyond that an. This tendency to seek a powerful "protector" arises from a desire for personal autonomy and shielding from threats, rather than trusting in broader systems of support and accountability. They promised to curb the oligarchs and the clan heads, and to lift the burdens from the people: seisakhtheia. Cancel the debts, abolish debt-slavery, redistribute the land, and then rely on the high regard of the people for them to keep them in power against an oligarchic or clan-network based reaction.

In Corinth, Argos, Sikion, in Megara, and later far and wide, with the most famous of these tyrannoi, these Strongmen, being Peisastratos of the the Athenai and Agathokles of the Syracosioi—and later the failed and assassinated C. Sempronius Gracchus of the Res Publica Romana. To those who actually wanted redistribution and general prosperity as much as to gain and wield power we can add William Jennings Bryan and Franklin Delano Roosevelt as having the same aims but different, constitutional means. And, I think, Lula da Silva in Brazil, though it remains to be seen whether he will ultimately be judged as a successful leader.

Originally the tyrannoi were not seen as especially bad: it was a value-neutral word. Platon of the Athenai changed that in Book 8 of his Politeia, where he described tyrants as men become wolves who merely “hinted at” debt-cancellation and land-redistribution, for above all else they desired power. Indeed they did. Thrown out of Athens twice Peisistratos so much wanted to rule that he came back a third time and ruled afterwards for two decades. Truly populist tyrants were, I think, by and large a good thing who did much to reorder their societies and prepare the way for the flourishing and efflorescence, astonishing in its time, of Classical Hellenic democracy.

To some degree it was Platon’s aristocratic background that gave him his very jaundiced view of the tyrannoi. His real name, after all, was Aristo-kles, the son of Aristo-n. You cannot get more aristo-cratic than that, can you? But more important, I think, is the tyrannoi and tyrannoi wannabes that Platon saw up close. He saw Alkibiades and Kritias of the Athenai. He saw Dionysios I, Dionysios II, and Dion of the Syracosioi. Dionysios II, or so the story goes, arrested him and had him sold as a slave. And these politicians were always much more about seizing and holding the power than about lifting the burdens from the people.

Thus I propose a three-part classification for practitioners of Strongman, leadership politics:

Populists, for whom lifting the burdens from the people and gaining for them the power to prosper and lead their own lives is at least as important as being boss and leader.

Pragmatists, who cancel the debts and redistribute the land only to the extent that it strengthens their backing coalition without making for them too many and too fierce enemies.

Fascists, who say that I am not here to serve the people, but rather the people are here to serve me—to help me become powerful and glorious, to secure my rule as boss, to gain satisfaction by vicariously participating in my glory and taking on as their own the missions that I decide the government I head should pursue, and in return I will protect them from their enemies.

Yes, the F-word. I think it is appropriate. I think we need it. I think it is important to distinguish between whether populists are in it for the lifting of burdens from the people, those who have chosen the opposite of Team Oligarchy for instrumental reasons as a road to power, and those who have glorious purpose who seek to attach the people to that purpose—who believe that the happiness people ought to and are only truly satisfied is not some bottom-up utilitarian happiness of comfort and prosperity given what people want and think they need, but the happiness of participating in some collective project and attaining some collective goal chosen for them by the leader who tells them what they really need, and just what they want.

Perhaps Alkibiades was the first fascist. His biography is worth pondering.

In decreasing order of viciousness, Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Putin, Pinochet, Orban, Duterte. Shading into still lesser degrees for which the description applies less well, figures like Erdogan and Modi. Leaders who are not genuinely interested in addressing the people's struggles or redistributing wealth. Leaders interested in power and glory, primarily their own. And leaders who solidify power by making people believe that they are protected against threats. It is far more effective to make people believe they are protected against fabricated and fake threats. Protecting people against imaginary threats and thus making them feel grateful is easy. Protecting people against real threats, and generating real threats by telling people that others who are not powerless are threats, is potentially difficult and may be a big cause of trouble.

Here we note that Adolf Hitler was unique: he turned the entire rest of the world into his deadly and unforgiving enemies.

And then there are those I have a hard time classifying: Strongman, yes, but populist, pragmatist, or fascist? Two such from the past are Andrew Jackson in the United States in the 1830s and Charles Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte in France in the 1850s are interesting edge cases that often puzzle people in terms of which political side they represented. Two such I find puzzling in the present are Britain’s Boris Johnson and America’s Donald Trump: interesting edge cases in the present political landscape. Boris Johnson is especially puzzling: he was not very pragmatic in power, the enemies he promised to protect the British people from—bureaucratic Europeans—were totally fake—yet when he became totally dominant Prime Minister of Britain he had absolutely no idea what he actually wanted to do with his power, no idea of either what the prosperity of the people or his own glory required.

And as for Donald Trump, we will see.

Perhaps the most interesting of these edge cases is Charles Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of the great military commander Napoleon, who made himself Napoleon I, Emperor of the French, back in 1804. Louis Bonaparte became President of the Second French Republic in 1848. He then declared himself Emperor Napoleon III in 1852, founding the Second French Empire, which lasted until 1870. He did so despite having no qualifications other than his ability to speak persuasively and his status as nephew of Napoleon the Great. was able to win power in, become the dictator of, and for two decades rule the world’s second most powerful and developed country at the time. Karl Marx and the Rothschild family—who agreed on literally nothing else—100% agreed that he was a total idiot, unqualified and incompetent. And yet he did it…

We have an era of Strongman politics. Figuring out how to channel their energies into truly populist rather than fascist political movements is but one of the many, many key challenges in and keys to successfully resolving our polycrisis.

5.4.9. Polycrisis: War & Rumors of War:

The unprecedented devastation of World War II coupled with the development of nuclear weapons took great-power war off the table. It was simply too risky, and too destructive. The US would wage a Cold War against Stalin’s, Khrushchev’s, and Brezhnev’s Russia and against Mao’s China, but nobody wanted a hot war, let alone a nuclear hot war. The prospect of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) played a critical role. The Cold War was a fierce ideological struggle. It saw a lot of low-level proxy wars. But direct major-power confrontations? After the 1950-1953 Korean War saw US fighting Russian pilots in the air and US fighting Chinese soldiers on the ground, all three powers were very careful not to get themselves into any situation in which that might happen again. Wars were geographically constrained, largely guerrilla, and low-intensity. That was the post-WWII norm.

The post-WWII norm began to erode in 1980, when the US Carter administration, smarting from the seizure of the US embassy s taff as hostages by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, did not say no to Saddam Hussein’s launching what he saw as a preëmptive strike against Iran’s Shia theocracy. Furthermore, the Reagan administration then made sure Iraq stayed well-supported in its war by Saudi Arabia, and that the flow of oil through the Gulf to maintain Saudi prosperity was maintained.

The norm eroded further with Saddam Hussein’s conquest of Kuwait in 1980 and the 1990-1991 First Gulf War, launched by the George H.W. Bush supported by Dick Cheney and Colin Powell. Operation Desert Storm ejected Iraqi forces from Kuwait, showcasing the overwhelming military superiority of the United States. But it went no further. Bush 43, Powell, and then-Cheney concluded, I think wisely, that they should establish the norm that the US military was both at the disposal of and yet in major actions constrained by the UN Security Council. A US military constrained by a need to seek Security Council approval was a threat to few, and nearly all would conclude that they did not need themselves to arm against it. And yet a US military that would move when empowered by the Security Council promised to be an effective threat and peacekeeper.

But the norm further eroded. President Clinton changed the game so that not Security Council but NATO alliance permission would also serve, much to Russia’s dismay. 911 and the decision by Bush 45 and the later Cheney to attack Saddam Hussein’s Iraq—never mind that Osama bin Laden hated Saddam Hussein almost as much as he hated the United States—took off the brakes. Powers with interests seen as adverse to the US took note, and began to arm significantly. And once you have a large army you start looking for places and ways to use it.

Putin’s Russia did much more than merely flex its muscles in the Caucasus portions of the “near abroad”, and against independent Ukraine in 2014 with the seizure of Crimea and pieces of the Donbas—never mind Russia’s scrap-of-paper 2004 signature guaranteeing the independence and territorial integrity of Ukraine.

But nobody expected 2022, and Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. That shattered the long-held assumption that war between major powers was too destructive to contemplate. The invasion represented a fundamental challenge to the post-WWII international order.

And as goes Vladimir Putin’s Russia and Ukraine, will so go Xi Jinping’s China and Taiwan?

A realistic appraisal from Beijing would look at Taiwan and conclude that this is a sleeping dog that should be let lie. Maximize economic and cultural ties with Taiwan, yes—make its links with China key to its prosperity and its cultural identity. But make politicians in Taipei keep their jobs only at the pleasure of Beijing? Not worth the potential trouble.

After all, the history of China since 1976 demonstrates that China is much safer and stronger when it is one country, two (or three, or four) systems. And governmental bureaucratic and ideological desires to centralize make maintaining separate systems difficult with more than the lightest of governmental-administration touches. Deng Xiaoping and his successors were able to make China rich only because they could start out by borrowing the entrepreneurial classes first from British Hong Kong and next from Guomindang Taiwan. Had Mao conquered both in 1949, I do not believe the PRC would have lasted to 1989.

In fifty years, one of two things will be clear. Perhaps China will be a rich great-power success, with Socialism with Chinese Characteristics—Authoritarian State Surveillance Capitalism with a Leninist Party in Command and Egalitarian Aspirations—a great success as well, in which case Taiwan and the rest of China will be as interdependent and have as little to argue over as the United States and Canada, and the issue will seem quaint. Or Socialism with Chinese Characteristics will fail—in which China will need alternative systems not just economic but political as well more badly than ever.

But the view from Beijing does not seem a clear-eyed one.

Add the prospect of more major-power wars as the final dimension of our current polycrisis.

5.4.9. Conclusion: Hope?

Let me conclude with two quotes, from Adam Tooze and John Maynard Keynes, giving us some hope. Keynes is one of Tooze’s heroes, and he looks to him for clues as to how to successfully surmount the polycrisis “challenges” of our current interregnum:

[English philosopher John Maynard] Keynes is one of the most interesting meta-theorists of how you deal with complex, entangled problems which are much worse than they need to be as a result of failed political coordination. In the wake of World War One, a very different polycrisis from our current moment, he's trying to demarcate and arbitrate this question of which bits of the problem we should handle and how.

He thinks you need to take certain problems off the agenda. So the problem of unemployment or excessively high interest rates can be addressed by economic policy. He's trying to offer a set of technical fixes that allow you to take those issues off the board so that then you can concentrate the limited political capital, the building consensus of a functioning democracy, on issues which are harder to resolve and where genuine political agreement is needed.

And that seems to me to be a model for thinking about our current moment…”

As, indeed, Keynes did play a significant role in bringing an end to the last such interregnum:

THE outstanding faults of the economic society in which we live [as of 1936] are its failure to provide for full employment and its arbitrary and inequitable distribution of wealth and incomes. The bearing of the foregoing theory on the first of these is obvious. But there are also two important respects in which it is relevant to the second….

The growth of wealth, so far from being dependent on the abstinence of the rich, as is commonly supposed, is more likely to be impeded by it. One of the chief social justifications of great inequality of wealth is, therefore, removed….

[We should] reduce the rate of interest… [which] is likely to fall steadily… [if we] maintain conditions of more or less continuous full employment…. This state of affairs would be quite compatible with some measure of individualism, yet it would mean the euthanasia of the rentier, and, consequently, the euthanasia of the cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist to exploit the scarcity-value of capital….

The authoritarian state systems of today seem to solve the problem of unemployment at the expense of efficiency and of freedom. It is certain that the world will not much longer tolerate the unemployment which, apart from brief intervals of excitement, is associated and in my opinion, inevitably associated with present-day capitalistic individualism. But it may be possible by a right analysis of the problem to cure the disease whilst preserving efficiency and freedom…

References:

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin & Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. <https://archive.org/details/imaginedcommunit0000ande_f5f1>

Brinkley, Alan. 1982. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, & the Great Depression. New York: Knopf. <https://archive.org/details/voicesofprotesth0000brin>.

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2024. "Misinformation Decided the US Election." Project Syndicate. November 11. <https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/2024-election-surveys-show-trump-voters-misinformed-on-major-issues-by-j-bradford-delong-2024-11>.

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2024. "A Very Peculiar Kind of Triumph of the Will." Grasping Reality. November 8. <https://braddelong.substack.com/p/a-very-peculiar-kind-of-triumph-of>.

Eichengreen, Barry. 2018. The Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance & Political Reaction in the Modern Era. New York: Oxford University Press. <https://libgen.is/book/index.php?md5=E0A1A1B1C2D3E4F5G6H7I8J9K0L1M2N3>.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. 1979. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications & Cultural Transformations in Early-Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. <https://archive.org/details/printingpressas01eise>.

Ferguson, Niall. 1998. The House of Rothschild: Money's Prophets, 1798–1848. New York: Viking. <https://archive.org/details/houseofrothschil00ferg>.

Gellner, Ernest. 1983. Nations & Nationalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. <https://archive.org/details/nationsnationali00gell>.

Gellner, Ernest. 1988. Plough, Sword, & Book: The Structure of Human History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. <https://archive.org/details/ploughswordbooks0000gell>.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, & Money. London: Macmillan. <https://archive.org/details/generaltheoryofe0000john_b2t4>.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1962. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. <https://archive.org/details/gutenberggalaxym0000mclu>.

Marx, Karl. 1852. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. New York: Die Revolution. <https://archive.org/details/18thbrumaireoflo00marx>.

Neumann, Franz, Herbert Marcuse, & Otto Kirchheimer. 2013. Secret Reports on Nazi Germany: The Frankfurt School Contribution to the [American World] War [II] Effort. Ed. Raffaele Laudani. Princeton: Princeton University Press. <https://archive.org/details/secretreportsonn0000neum>.

Platon (Aristokles Aristonos of the Athenai). 1997 [ca. -347]. Complete Works. Ed. John M. Cooper & D. S. Hutchinson. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. <https://archive.org/details/plato-complete-works>.

Riefenstahl, Leni, dir. 1935. Triumph of the Will. Germany: Leni Riefenstahl-Produktion. <https://archive.org/details/TriumphOfTheWillgermanTriumphDesWillens>

Shklar, Judith Nisse. 1989. "The Liberalism of Fear." In Liberalism & the Moral Life. Ed. Nancy L. Rosenblum, 21–38. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. <https://speculativematerialism.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/shklar-liberalism-of-fear.pdf>.

Tooze, Adam. 2023. "We’re in a ‘Polycrisis’ – a Historian Explains What That Means." World Economic Forum. March 7. <https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/03/polycrisis-adam-tooze-historian-explains/>.

Young, Clifford, Sarah Feldman, & Bernard Mendez. 2024. "The Link Between Media Consumption and Public Opinion." Ipsos. October 18. <https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/link-between-media-consumption-and-public-opinion>.

I like this analysis a lot, but I do have a couple of disagreements. First, as I said in a comment on a previous post, I don't think there are any legitimate populists. The vast majority of "populism" is merely rhetorical, designed to bring the "populist" into power so that he and his friends can be in charge instead of that other guy and his friends. There could hardly be any better recent example than Trump, who relies on false promises to solve everyday problems combined with racist, misogynist, and other bigoted promises that play to fear of the "other". It's the same strategy we saw in the original Populist movement, in the Jim Crow South, in Italy in 1922, in Germany in 1933, in Hungary and India recently, and elsewhere. The only question is exactly where Trumpism will land on that spectrum, and there is no landing place that allows for much hope in the near future.

The other dispute involves a conclusion that I've come to only recently and with a great deal of regret. I now think that capitalism and democracy are incompatible. The reason is that capitalism creates two major problems. You identified the inequality arising from Neo-Liberalism so I don't need to add anything here. But the other problem is that capitalism creates enormous uncertainty in the population at large: is my job secure? am I keeping up with my neighbors? are "those people" getting stuff that I deserve and they don't? Etc. That uncertainty translates very readily into fear. And whether fear leads to hate or fear is the mind killer, the result either way is an emotion which pseudo-populists and actual fascists can exploit.

I'd like to be optimistic here, if for no other reason than I want my grandchildren to live in a decent world, but right now I'm not. There were too many missed opportunities in the past 16 years and it's hard to see how we can get those back.

I fear the term 'neo-liberal' will confuse future students for at least a century. Were the ideas new or liberal? No, it was just a cynical label. Surely a better term can be created.