Possible? Introduction to “History of Economic Growth”, & BRIEFLY NOTED

For 2022-12-10 Sa

CONDITION: Sick, Sardonic Amusement:

It is unfair, but I still cannot help but keep thinking about and laughing at, in a sick way, Matt Yglesias’s hyperbolic description of how subservience to The FaceBook as a platform impelled by the desire to expand rapidly and make lots of money broke http://vox.com’s hopes to disrupt the media with first-class and useful explainer journalism:

To get a really big web audience, you need broad distribution from Facebook and Google…. That meant bending to the editorial vision of a different company….

Platform dependence made product innovation essentially impossible. It was also editorially constraining. I think it’s very under-appreciated by people in the technology industry that most of the media trends they deplore are direct consequences of Facebook’s influence over journalism in the mid-2010s….

Hard-core identity politics and simplistic socialism performed incredibly well on Facebook….

So you ended up with this whole cohort of discourse structured around “Is Bernie Sanders perfect in every way? Or is it problematic to vote for a white man?” as the only possible lens for examining American politics and society…

Truly we are damned!

I am trying to have some intelligent thoughts about the differences between:

organizations that have a mission, subject to a cover-your-costs constraint;

organizations that are about making as much money as they can; and

organizations that are about building tech-bro castles in the sky, so that founders can sell out to later funding rounds, and the whole thing can eventually be sold to a giant that fears a possible future competitive threat, and then shut down.

These three types of things act very differently.

But my thoughts are not yet intelligent…

FOCUS: Possible? Introduction to “History of Economic Growth”

Is this how I should start my course next semester?:

Let me talk for 15 minutes, and then let’s see if we can have a discussion here:

I take 1870 to be the hinge of history.

Starting in 1870 it became clear—with human technological competence deployed-and-diffused worldwide (not just in the southern part of one small island) doubling every generation—that humanity was on the way to solving the problem of baking, a sufficiently large economic pie for everyone to potentially have enough. Up until 1870 there had been no possibility of humanity baking such a sufficiently large economic pie. Technological progress was simply too slow. Human fecundity—and the desire to have surviving children, especially sons—was just too great.

The slowness pre-1870 of technological advance had two major consequences:

First, it meant that Malthusian pressures kept humanity desperately poor. Take slow technological progress. Add the necessity under patriarchy of having at least one surviving son in order to give one durable social power. Reflect that under conditions of slow technology and thus slow population growth, one-third of humans will wind up without surviving sons. to have more sons in the hope that at least one would survive, and natural resource scarcity—those put mankind under the Malthusian harrow, in dire poverty.

Second, it meant that politics and governance were a poisonous weed. In a world in which there cannot be enough, at the foundation politics and governance can be nothing else than an élite, elbowing competitors out of the way and running a force-and-fraud exploitation game on the rest of humanity. This élite of thugs-with-spears (and later thugs-with-gunpowder-weapons) and their tame accountants, bureaucrats, and propagandists could have enough. And with their enough they could build and enjoy their high culture. But that those who controlled and those who spoke were hard men, who reaped where they did not sow and gathered where they did not scatter, made human life fairly dystopian, even after taking account of the general poverty.

However, after 1870 it rapidly became clear that things could be very different: “Economic Eldorado”, as John Maynard Keynes put it, was on the way.

In 1870 the last pieces of the institutional complex that supported what Simon Kuznets labelled “Modern Economic Growth”—average real income and productivity levels doubling every generation, growing at an average rate of 2%/year or more—fell into place. The addition to the institutions that were there before pushed humanity across a watershed boundary with the coming of

the industrial research lab,

the modern corporation, and

the globalized market economy

These revolutionized the discovery, development, deployment, and diffusion of human technologies useful for manipulating nature and cooperatively organizing ourselves. There was as much global technological advance from 1870 to 2010 as there had been from -6000 to 1870. Humanity’s deployed-and-diffused technological prowess in 2023 stood at a level at least 25 times its level as of 1870. And although there was a population explosion—humanity’s numbers rose from about 1.3 billion in 1870 to 8 billion in 2022—that explosion soon ebbed with the coming of the demographic transition, the rise of feminism, and the shift from high to low fertility. While before 1870 humanity’s ingenuity in technological discovery had lost its race with human fecundity, afterwards it decisively won it.

And yet, while things were different after 1870, they were not different enough. Finding the solution to that problem of baking a sufficiently large economic pie did not get us very far, because the problems of slicing and tasting the pie—of equitably distributing it, and of utilizing our wealth so humans could live, lives in which they felt safe and secure, and were healthy and happy—continued to completely flummox us.

At this point the flow of my thoughts divides into at least five rivers:

I find myself looking backward from 1870 earlier in time to understand how the pre-1870 impoverished Malthusian human economy worked—as a-mode-of-production, -distribution, -domination, -communication, and -innovation.

I find myself looking backward from 1870 earlier in time to trace how there was no alternative hinge. How was it that the Devil of Malthus had so ensorcelled humanity before 1870? How was it that its spell had been so powerful from -6000 to 1870?

I find myself looking at 1870 to trace how the hinge that 1870 was was the hinge happened. Given the pre-1870 power of humanity’s ensorcellment by the Devil of Malthus, how could we then wreak the miracle of breaking it? Why did no one think to gather communities of engineering practice to supercharge economic growth before 1870? How exactly did the research lab and the corporation in the context of the global market economy empower us to accomplish these tremendous feats? Was the explosion of wealth and productivity of 1870 causally-thin, in the sense that institutions had to evolve then in a way that was unlikely to get the explosion? Or was the growth acceleration of the Second industrial Revolution, the one big wave of Robert Gordon, causally-thick—largely baked in the cake, while the causally-thin nexus or nexuses came earlier? These are very hard and deep questions indeed.

I find myself looking forward from 1870 later in time to trace how the research lab-, corporation-, and global market economy-enabled discovery, development, deployment, and diffusion of technologies at an unprecedented, revolutionary, Schumpeterian creative-destruction, pace worked itself out, leading sector by leading sector and trailing sector by trailing sector. The David Landes-Joseph Schumpeter-Vaclav Smil book

I find myself looking forward from 1870 later in time to trace the political-economy consequences for human society of this unprecedented advance toward technology revolution-driven material cornucopia. Why, given that the solution to the problem of baking came within our grasp, did the second-order problems of slicing and tasting continue to elude us?

Plus, we need to always remember that humans do not just do, they think about what they are doing. We must cover not only what the economy in the process of economic growth or non-growth was, but also what people thought they were doing—and what they thought their options and possibilities were.

Now it is no secret that I have already set out my take on (5). It is my book: Slouching Towards Utopia: The Economic History of the 20th Century <bit.ly/3pP3Krk>.

The other four, however—well, economic historian Eric Jónes has a line:

Oscar Wilde expected to be met at the Pearly Gates by St Peter bearing an armful of sumptuously bound volumes and declaring, “Mr Wilde, these are your unwritten works”… [The European Miracle: Environments, Economies and Geopolitics in the History of Europe and Asia]

I find myself almost unmanned at the thought of the task of trying to write them.

But we do what we can. I draw inspiration from Will MacAskill’s whose very nice book What We Owe the Future is really six 50-page book prospectuses stapled together. I think: I can do that—I can provide you with lecture notes at that length (plus my Slouching Towards Utopia book) to guide our explorations this semester of these topics (1) through (5).

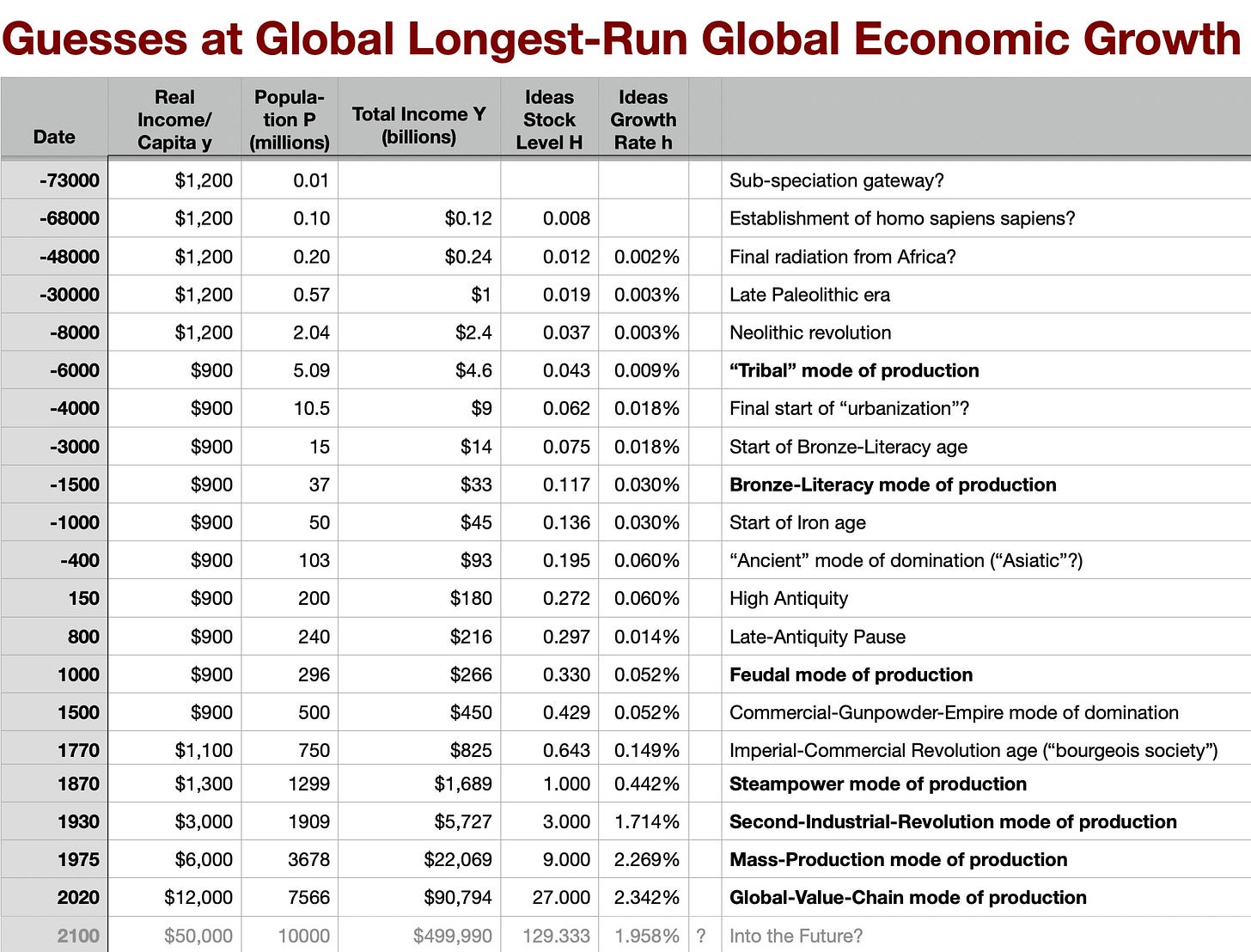

And throughout, I will structure what we do around this table of my guesses as to the shape of the human economy—how many people P, roughly what their average real income in today's dollars happens to be y, and then this measure of mine H, which is average real income times the square root of population which I will assert is a rough measure of human ideas about "technology": our capability to manipulate nature and productively organize ourselves. And population, average real income, and human ideas P, y, and H have their proportional annual growth rates n, g, and h, respectively:

What do you notice—what do you think we should notice as especially important—about this table of guessed-at numbers I am showing you here?

ONE VIDEO: Physics Sets Up a “Caution” Sign!

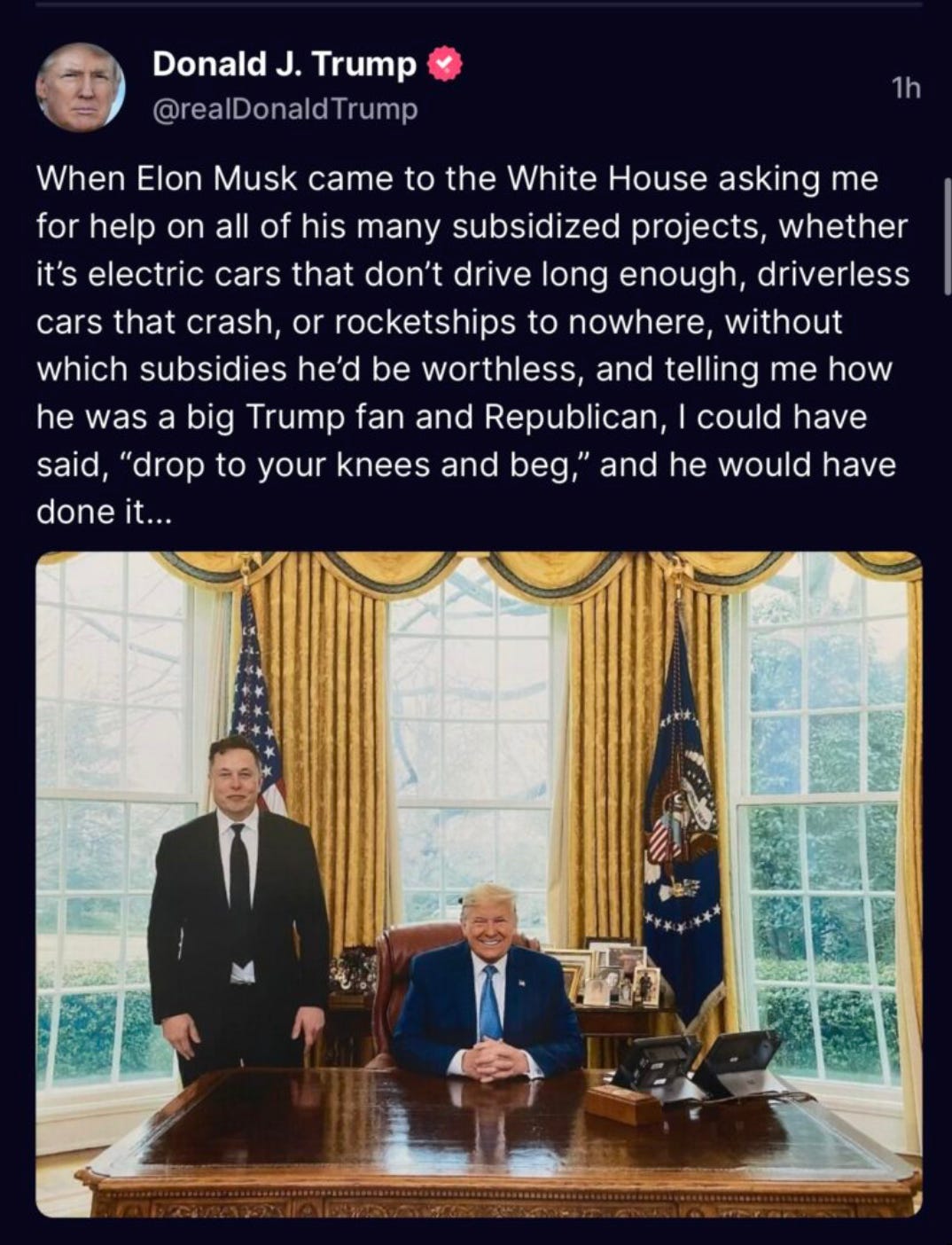

ONE IMAGE: What a Maroon!

MUST-READ: The Future Is Not Just Here & Unevenly Distributed, It Is Slipping into the Past:

Again, this greatly resonated with me:

Noah Smith: My cyberpunk city, my cyberpunk world: Cyberpunk assembled itself in our minds, a vision composed half of a technological and social future we felt was coming, and half of the adventures we imagined ourselves having…. And then those adventures became not just possible, but inescapable and terrifying. In 2019 I found myself standing on the roof of a skyscraper in Hong Kong next to a friend in a gas mask as the city’s youth and mirror-faced riot police battled each other with tear gas and firebombs in the electric forest of the megalopolis below. Those brave, doomed Hong Kong protests were, in fact, just one part of a multi-year global uprising in which people around the world fought their governments and their local police forces in the streets, coordinating and inspiring each other and outfoxing the authorities using a global wireless communication network linked to pocket supercomputers running pseudonymous social media services. The uprising continued even in the face of a sudden global plague that had much of the world hiding in their rooms, linked only by video chat, ordering their goods on the web.

In the wake of the plague came war. Drones.. indispensable…. Where soldiers once sent poetry from the front, now they sent high-quality videos, often with a soundtrack from popular music…. And the war extends its tentacles into the social media space, a shadowy realm where it’s hard to tell the difference between the bots, government operatives, and online fandoms spewing out clouds of information and disinformation—great-power politics played out in forum flame-wars.

Far from the war, I walk through the streets of a strange cyberpunk city. I step around the homeless, destitute people who fill the streets, forsaken by their increasingly distant government. Strange people roll past me on one-wheels carrying boomboxes blasting 90s rap, fly drones in the park, scoot around in homemade go-karts, or drive miniature fake firetrucks blasting sound effects from Godzilla. And laid over this gritty, failing, beautiful metropolis like a second city: the network of the eccentric barons of techno-capital and their hired geniuses, the corporations that own space and create miracle medicines and godlike pseudointelligences, all connected by digital threads of memes and money and the occasional trans-national cyber-scam.

That girl with the chrome hair and the black leotard and the gizmos implanted under her skin? I know that girl, she lives down the street from me.

We felt this future coming; we didn’t need prophets to tell us about it. We saw how information technology was wiring up the world, how inequality was breaking society into pieces, how governments were struggling to deal with it all. The elements of the genre we now know as cyberpunk were pasted onto that consensus mental collage. Gibson, Stephenson, Shirow, Oshii, Sterling, Cadigan, and all the other cyberpunk creators were simply offering us alternative little slices of a future we all felt being born around us. And now we’re here…

Oþer Things Þ Went Whizzing by…

Very Briefly Noted:

Annie Lowrey: Harassment in Economics Doesn’t Stay in Economics…

Chris Anstey: India’s Economic Ascendance May Happen This Time: ‘China’s economy zoomed past India back in the early 1990s... following the initial chapters of the high-growth playbook. Now, just as China is running into major headwinds, India has the chance to emerge as a new dynamo.... But hopes for India to achieve East Asian-style rapid growth have disappointed before.... Two key things have changed. First... New Delhi is putting its money where it’s mouth has been in terms of building infrastructure.... Second, the widening rift between the US and China....

Paul N. Pearson & al.: Authenticating coins of the ‘Roman emperor’ Sponsian: ‘An apparent contradiction in the historical sources…. On the one hand that the Province of Dacia was lost to the empire in the reign of Gallienus, but also… Aurelian… evacuated the people… to a new province… south of the Danube… [Perhaps] an initial period of isolated secession when supply lines were cut off, followed by a negotiated and orderly withdrawal across the river when the security situation improved…

Matthew Yglesias: ‘I’ve posited a different mechanism for this — the purpose of conservative politics is to trick people into voting against redistribution, so it’s inherently a friendly space for scammers…

Scott Lemieux: Advertisers continue to flee Elon’s fascist midlife crisis: ‘Apparently buying a website with the sole purpose of featuring more Nazi content is an effective way of repelling advertisers, which is kind of a problem when advertising is the overwhelming majority of your revenue…

Anil Dash: ‘All other things aside, , the fact that [Musk] clearly doesn’t know how to use GitHub or Slack is such outrageously funny boomer energy. Fully in keeping with “print out your code” and “I am constantly getting duped by obviously fake bullshit online”…

Bruno Laeng & al.: Bright illusions reduce the eye's pupil: ‘The most parsimonious explanation for the present findings is that pupillary responses to ambient light reflect the perceived brightness or lightness of the scene and not simply the amount of physical light energy entering the eye. Thus, the pupillary physiological response reflects the subjective perception of light and supports the idea that the brain's visual circuitry is shaped by visual experience with images and their possible sources…

Scary Lawyer Guy: ‘Six years later and reporters (in this case Blake Hounshell bringing that signature POLITICO style to the NYT politics desk) pretend they had nothing to do with creating an impression among voters that Hillary was corrupt. Nope, totally clean hands…

¶s:

But this is likely to be the end of the crypto grift bubble as we have known it, no? There is a future of Web3 and some DeFi out there for the TechBros, but this idea of plundering the easily gifted by making it easy for them to buy shitcoins with one button press on an exchange’s smartphone app—that is now a thing of the past? Right? Right?:

Ken Rogoff: Will Crypto Survive?: ‘The epic collapse of… FTX, looks set to go down as one of the great financial debacles of all time.... But… rumors of the death of crypto itself have been much exaggerated.... Vitalik Buterin... has argued that the real lesson of FTX’s collapse is that crypto needs to return to its decentralized roots. Centralized exchanges such as FTX make holding and trading cryptocurrencies much more convenient, but at the expense of opening the door to managerial corruption.... It is unlikely that the most important player, the US, with its weak and fragmented crypto regulation, will undertake a bold strategy anytime soon. FTX may be the biggest scandal in crypto so far; sadly, it is unlikely to be the last…

Is this the first presentation in popular literature of magic sorcery-as-technology?

Christopher Marlowe: The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus: ‘Now that the gloomy shadow of the earth,/Longing to view Orion's drizzling look,/Leaps from th' antartic world unto the sky,/And dims the welkin with her pitchy breath,/Faustus, begin thine incantations,/And try if devils will obey thy hest,/ Seeing thou hast pray'd and sacrific'd to them./Within this circle is Jehovah's name,/Forward and backward anagrammatiz’d,/Th' abbreviated names of holy saints,/Figures of every adjunct to the heavens,/And characters of signs and erring stars,/By which the spirits are enforc'd to rise:/Then fear not, Faustus, but be resolute,/And try the uttermost magic can perform.—/Sint mihi dei Acherontis propitii! Valeat numen triplex Jehovoe!/Ignei, aerii, aquatani spiritus, salvete! Orientis princeps/Belzebub, inferni ardentis monarcha, et Demogorgon, propitiamus/vos, ut appareat et surgat Mephistophilis, quod tumeraris:/per Jehovam, Gehennam, et consecratam aquam quam nunc spargo,/signumque crucis quod nunc facio, et per vota nostra, ipse nunc/surgat nobis dicatus Mephistophilis!…

Alice is right here, right? The behavior of both the New Yorker and the American Anthropological Association was insane and malevolent, right?

Alice Dreger (2011): Darkness’s Descent on the American Anthropological Association: A Cautionary Tale: ‘In his 2000 accounts of the 1968 epidemic (including his New Yorker article and book manuscript), Tierney had portrayed the anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon and the late geneticist-physician James V. Neel, Sr., as virtually amoral eugenicists bent on conducting inhumane and deadly field experiments on a phenomenally vulnerable population…. The truth was quite the opposite…. Neel had determined that the Yanomamö were alarmingly vulnerable to measles, and so he had personally arranged to bring vaccines…. Neel, Chagnon, and the others raced to try to contain the epidemic and get ahead of it with the vaccines. The medical supplies began to run out before everyone could be appropriately vaccinated, but it was not because of some neglect on Neel’s or Chagnon’s part…. Chagnon ought to be remembered not as the genocidal maniac of Tierney’s fantasy, but as the key provider of logistics during the frantic medical response to the tragic epidemic. I had to wonder when I came upon this story years after all this, given the reality as evidenced by so very many documentary sources, how did Tierney’s falsehoods get as far as they did? To answer that, one must really understand how and why certain individuals—but especially leaders within the American Anthropological Association (AAA)—played a supporting role to Tierney’s work. This was a supporting role that ultimately threatened the AAA’s integrity and indeed the integrity of American anthropology itself…. This paper… chiefly seeks to highlight the problematic aiding and abetting of Tierney by scholars who had the power to know better and to do better…

Regarding Vox' sad story:. (BTW This app's editing features suck). Your alternatives boil down to mission, money, and tech-bro. A useful framework for analyzing these cases might be the Yugoslav experiment with worker self-managed enterprises. Capital markets do not seriously constrain startups initially. Mission driven startups require a charismatic founder, e.g. Steve Jobs. Money grubbing startups require founders principally motivated by money. Jobs probably left a lot of money on the table by refusing to licence the Mac OS. Bill Gates had no such inhibition about widely licencing DOS/Windows system. Tech-bro is best conceived of as a post graduate floating fraternity party. E.g. SBF and TFX.

The only question is what makes the rate of change of Ideas/technology change?