Discover more from Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality

PROJECT SYNDICATE: Xi's Historic Mistake

My June column, on the vital importance for China of a separate government controlling the island of Taiwan. China is not a country but rather a civilization, and so centralization is extremely...

…inappropriate for the long haul. Where would China be now if its armies had rolled into Hong Kong and Taiwan in 1949, and if those territories, too, had been subject to the tender mercies of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution? China today would then be desperately poor, and desperately weak…

J. Bradford DeLong: Xi’s Historic Mistake: If China historically had pursued the path that its current paramount leader, Xi Jinping, seems to want to take, it would not be a rising economic superpower. History shows that it is in China’s own interest to allow for more regional autonomy and less centralization.

BERKELEY—Late last month, the American actor John Cena issued a groveling public apology after having referred to Taiwan as a “country” in an interview to promote his latest film. He was using the term to refer to a linguistic media market with a discrete distribution channel, not to the status of the island of Taiwan in international law. The Chinese government would make no allowance for such distinctions.

What are we to make of this episode? Clearly, globalization has gone terribly wrong. The speech restrictions dictated by China’s authoritarian government apply not just to China but also, and increasingly, to the outside world. Even in my own day-to-day experience, I have noticed that far too many people now speak elliptically, elusively, and euphemistically about contemporary China.

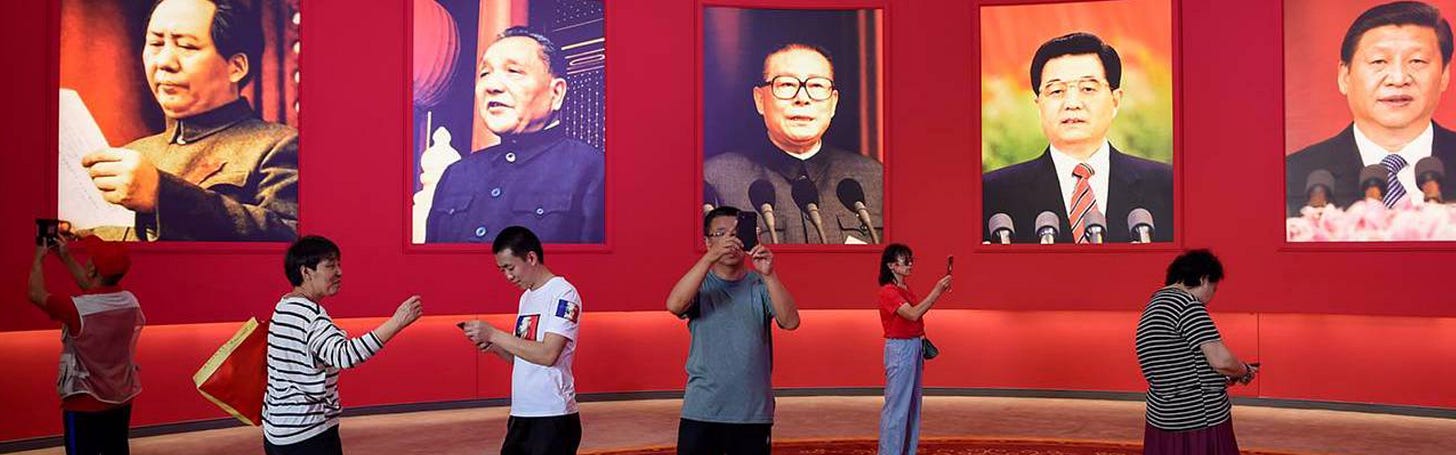

I could do that, too. I could subtly point out that no empire has ever had more than five good emperors in a row, and that it is important for a society to preserve a place for well-meaning critics like the sixteenth-century Chinese official Hai Rui, the early communist-era military leader Peng Dehuai, and the economic reformer Deng Xiaoping.

But I prefer to speak frankly and directly about the real issues that lie behind issues like terminological disputes over Taiwan.

In my view, it is in China’s own interest that the government in Taipei remains the sole authority on the island, so that it can continue to follow an institutional and governance path that is different from that of the People’s Republic. Likewise, it is in China’s interest that Hong Kong remains a third system. The government in Beijing ought to recognize that substantial regional autonomy, especially for areas with non-Han-majority populations, will serve its own long-term ambitions.

The appalling and tragic history of genocide, ethnic cleansing, and forced assimilation in the twentieth century suggests that top-down, imperial Sinicization will sow resentments that will last generations and create conditions for serious trouble in the coming years and decades. Humanity has grown up enough to know that diversity, regional autonomy, and cosmopolitanism are better than the alternatives. A regime that aspires to lead the world toward a brighter future should be especially cognizant of this.

Nonetheless, China’s current paramount leader, Xi Jinping, very much wishes to centralize authority in Beijing. Rightly fearing careerism and corruption in the Communist Party of China, he seeks not a Cultural Revolution but a Cultural Renaissance to restore egalitarian values and utopian aspirations across the leadership ranks. Supremely confident in his ability to read the situation and issue the right commands, his main concern is that his orders won’t be implemented properly. The solution to that problem, he seems to have concluded, is much greater concentration of power.

But even if Xi has made the right tactical calculation for the current moment, his own senescence, together with the logic of how authoritarian command organizations evolve, all but ensure that his strategy will end in tears.

It is a huge mistake to ignore the benefits that come with more regional autonomy. Consider an alternative history in which the People’s Liberation Army had overrun both Hong Kong and Taiwan in 1949; Sichuan had not been allowed to pursue pilot reform programs in 1975, when Zhao Ziyang was appointed provincial party secretary; and China’s centralization had proceeded to the point that the Guangzhou Military District could not offer Deng refuge from the wrath of the Gang of Four in 1976. What would China’s economy look like today?

It would be a basket case. Rather than enjoying a rapid ascent to economic superpower status, China would find itself being compared to the likes of Burma or Pakistan. When Mao Zedong died in 1976, China was impoverished and rudderless. But it learned to stand on its own two feet by drawing on Taiwan and Hong Kong’s entrepreneurial classes and financing systems, emulating Zhao’s policies in Sichuan, and opening up Special Economic Zones in places like Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

At some point in the future, China will need to choose between governmental strategies and systems. It is safe to assume that relying on top-down decrees from an aging, mentally declining paramount leader who is vulnerable to careerist flattery will not produce good results. The more that China centralizes, the more it will suffer. But if decisions about policies and institutions are based on a rough consensus among keen-eyed observers who are open to emulating the practices and experiments of successful regions, China will thrive.

A China with many distinct systems exploring possible paths to the future might really have a chance of becoming a global leader and proving worthy of the role. A centralized, authoritarian China that demands submission to a single emperor will never have that opportunity.

(Remember: You can subscribe to this… weblog-like newsletter… here:

There’s a free email list. There’s a paid-subscription list with (at the moment, only a few) extras too.)

Xi in particular has a very fragile ego (he can't even tolerate being compared to Winnie the Pooh) and is going to make a lot of horrendous decisions. Central authority is already weak on areas where it SHOULD be strong, like suppressing coal-burning (orders from central are don't burn coal, but many provincial governors have just been ignoring it). I think his obsession with centralization is because he's already lost; central control in China is already gone, and he's trying to make sure nobody notices. I see either collapse and warring states in China's near future, or more likely, a palace coup to oust Xi and put in someone competent instead.

That's the most optimistic article I have read in a long time! (Joking.) We can be fairly sure Xi pays no attention to the professor. So the next question is how will China act out when things do not go as (centrally) planned? And what are the best policies we and other liberal societies can adopt to mitigate the effects? Containment policy, anyone?