Viewing Sparta, & Ancient Society More Generally

Pre-industrial élites are, primarily, vicious & brutal gangs of thieves. So how can one write or read or think about þem wiþ anything but a shudder of disgust? Schizophrenia! We should shudder in...

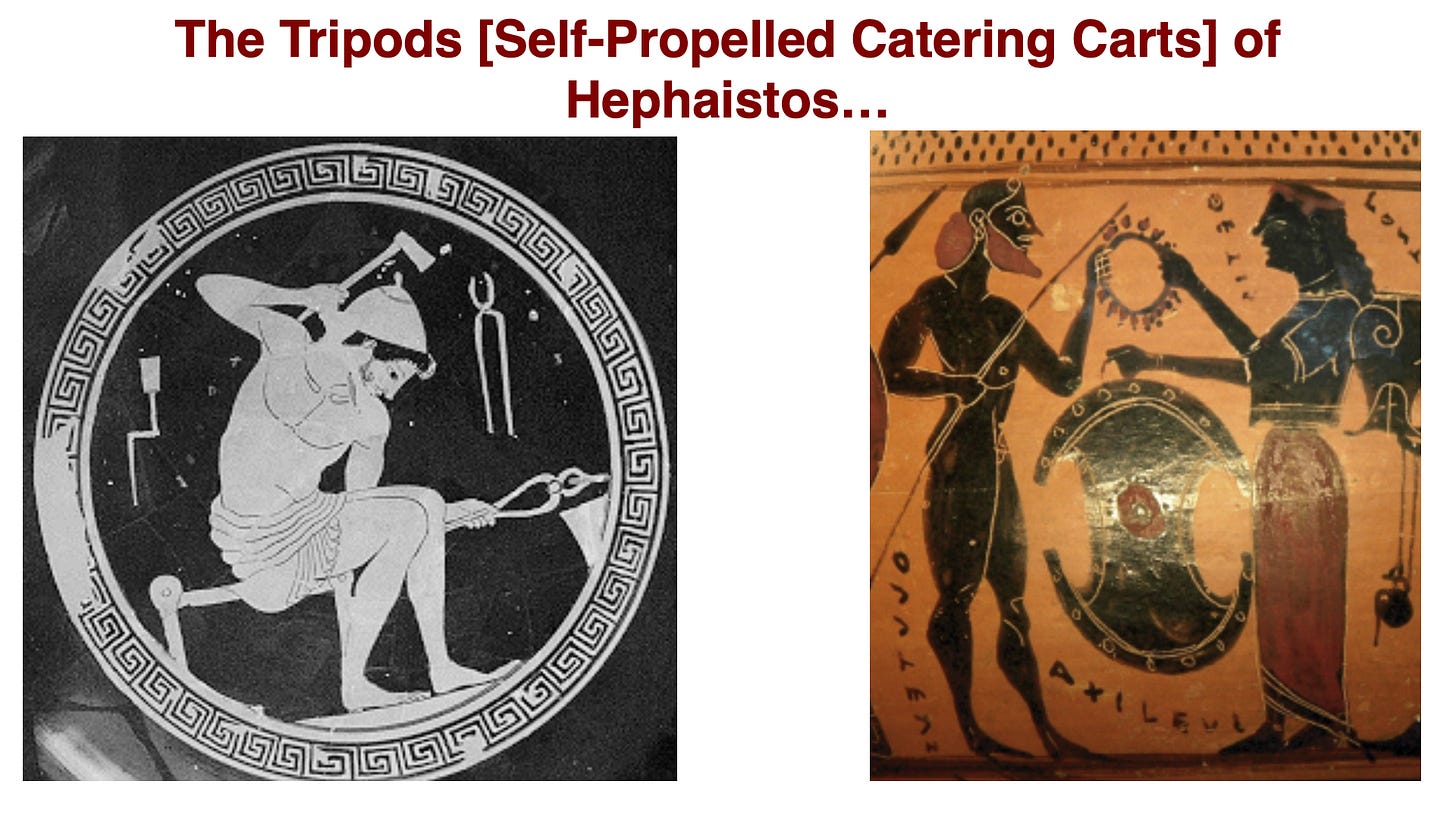

…disgust! But we can also look on the character of the élite’s relationships within itself all the way down. Is it a simple chain of domination, brutality, fear, and anger-management failures? Or can there be more? Worse or better, not so blameworthy or blameworthy, regressive or progressive aspects to past historical régimes—but all built on top of the force-and-fraud domination-and-extraction resource theft game that élites ran on the rest of their societies. Why did they run them? Because it was the only way they could get enough for themselves and their families, given that they did not have looms that wove by themselves or lyres that played themselves or the autonomous AI catering carts of Hephaistos or the robot blacksmiths of Daidalos...

Reasons Not to Tell þe Thermopylai Story:

I can think of four reasons why we should not tell Herodotos’s and Steven Pressfield’s versions of the story of Leonidas and the 300 Spartiates at Thermopylai:

The first is that the Spartans are simply not fit models for us to admire—at all, in any way, for any purpose.

The second is that it, over and above that, is a story that glorifies the social practice of war, and humanity should not be in the business of doing that.

The third is that Herodotos’s story is not historically accurate, and yet people will take it to be so, for we inevitably read it—and historical fiction based on it‚not as mythology or fiction or fantasy but as true history.

The fourth is that the story will be destructively misread by the weak-minded—that even though the story itself is a fascinating one, too many people h weak minds and will misread it to their (and our) great detriment.

I covered (2), (3), and (4) in:

To recap, briefly: (4) The “misreading” story is not something I have an answer to; I can only (a) it is certainly illiberal, but (b) the dodge that if we add more speech by discussing misreadings we can fix the problem is just that—a dodge—; (3) I agree we should teach Leonidas as seen by Herodotos and Pressfield and others not as history but as the mythology the Spartans told others and told themselves; and (2) I reject: war is a human social practice, and we ill-serve ourselves by attempting to ignore it by not talking about it, and thus not grappling with it.

But that post ended with: Sparta, and Ancient Society More Generally: And now, finally, I have come to the end of my list of objections. But this is already too long. So I will deal with the question of how we should view human predecessor societies—especially Sparta—some other time.

I simply ran out of steam, and said that I would return to it later…

Well, now is later…

Typical Lives in the Early Days of Civilization, -3000 to 1500

Well, now is later:

The post-agriculture post-metalworking pre-industrialization pre-globalization human economy is a good place to start our narrative of the history of economic growth. So let us ask: What was human life like in the early days of civilization, in the long Agrarian Age of bronze and iron and writing, after the discovery of metals and writing but before reliable trans-oceanic travel, in the years from, say, -3000 to 1500?

Our standard of living back then? If we had to slot it into emerging-markets standards of living in the world today, then for typical people—not the élite—we might call it $2.50 a day. Back then technological progress was so slow and resource scarcity so great that if the average human population grew at 8% per century—which it did from -3000 to 1500—potential benefits from technology enabling better use of resources and thus higher productivity would be offset by scarcer resources per capita and thus lower productivity. From -3000 to 1500, I cannot see any significant difference in the material standard of living of the typical person. (Of course, the élite of 1500 had lives far outstripping in wealth those of -3000, and the typical person in 1500 had much greater cultural wealth accessible to them, if they could grasp it, than their predecessors in -3000.)

Now civilized human populations growing at an average pace of 8% per century for 4.5 millennia should make us sit up and take notice. We know a preindustrial pre-artificial birth-control population that is nutritionally unstressed will triple in numbers every 50 years or so. That was the experience of the conquistadores and their descendants in Latin America. That was the experience of the English and French settlers coming in behind the waves of plague and genocide that had decimated the indigenous Amerindian population in North America. That was the experience of the Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian settlers on the Pontic-Caspian steppe, after the armies of the gunpowder empires, most notably of Yekaterina II Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov (neé Sophie), Tsarina of All the Russias, drove out the horse nomads and opened the black-earth regions to the plow.

And yet it took not 50 but 1500 years for human populations to double in the long Agrarian Age of civilization from -3000 to 1500.

Thomas Robert Malthus taught us that there are two ways that a human population can be kept from exploding—from doubling every fifty years, and multiplying by a thousand-fold every 5000. There is the positive check: people so poor and malnourished that children’s immune systems are compromised so that they get carried off by the common cold, and women so poor and hungry that ovulation becomes hit-or-miss. And there is the preventative check: late marriage for women, social shunning of those who engage in extra-marital intercourse, and conscious fertility limitation by couples so that you can live relatively well without the population exploding.

Back in the Agrarian Age, the check for the typical family was overwhelmingly the positive one: poverty, malnourishment, hunger, and their consequences.

Why? I blame, among other things, patriarchy:

There is a story told about Eli’sha (“Father God Is My Salvation”), Prophet in Israel in the first half of the -800s:

[In] Shunem… a wealthy woman lived…. And she said unto her husband, “Behold now, I perceive that this is an holy man…. Let us make a small roof chamber… so that whenever he comes to us, he can go in there.” One day he came there… turned into the chamber and rested there And he said to Geha’zi his servant… “What then is to be done for her?” Geha’zi answered, “Well, she has no son, and her husband is old.” He said, “Call her.” And when he had called her, she stood in the doorway. And he said, “At this season, when the time comes round, you shall embrace a son”… (2 Kings 4:8-16 RSV)

The question is: What can a prophet with mighty and magical powers do for this wealthy woman who has assisted him? The answer is: Get her a son!

And there is more: Sixteen Bible verses after Elisha promises the wealthy Shunamite woman that God will grant her a son, we read: “When Eli′sha came into the house, he saw the child lying dead on his bed…” (2 Kings 4:32 RSV). And in the next five verses Eli’sha went above and beyond his tasks as Prophet of Israel, and raised the boy from the dead—a feat I do not think is found elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible save for a similar resurrection of the son of the widow of Zar’ephath by Eli’sha’s teacher and patron Eli’jah (“My Storm God Is Father God”).

In the year -3000 we think the population of the world was about 15 million. By 1500 we are pretty confident that it was about 480 million. That is an average human population growth rate of 0.077% per year. That is an average population growth rate of 2% per generation. Typical women in the years from -3000 to 1500 would thus have, an average. 1.02 sons who themselves survive to reproductive age Do the Poisson-distribution math. Recognize that that means only two women in three have sons who survive into their mothers’ middle age.

What did it mean back then to be in the other one-third of women—those without surviving adult sons?

Well, having a surviving son was a great gift. Under conditions of strong patriarchy, indeed, not having a surviving son was close to—not quite, but close to—social death. If you don’t have a surviving adult son, then when your—perhaps older—husband is dead, who is going to speak up for you, and make sure you get any resources at all? Your daughters? Only if you have very good relationships with your sons-in-law. Your nephews? Perhaps. Wherever patriarchy was sufficiently strong—and that was lots of places—the consequence of winding up sonless were dire. And the chance of winding up sonless was high: 1/3.

The result was that whenever, wherever there were extra resources, the pressure to use those resources to try to have more sons as insurance was immense. Thus whenever, wherever we gained the ability to grow more food, we would simply have more children. Population thus pressed on the means of subsistence. People are trying to have many sons given that infant and early childhood mortality was between 1/3 and 1/2 and the expected number of surviving sons was just a hair over one. Figure eight or nine pregnancies, six or seven live births—and lifetime maternal childbed mortality between 1/10 and 1/5—three or four children surviving to age 5 and two or three surviving to adulthood, leaving just over two surviving and reproducing.

Thus whatever social institutions you developed, their ability to restrict fertility—and thus boost the incomes of the typical above levels we would see as $2.50 a day per capita—was very limited. Where wiggling around those institutions would raise your chances of having a surviving son, people would wiggle.

And so even though technology in 1500 was far advanced over technology in -3000, the typical person in 1500 was little better off; life remained nasty, brutish, and short in spite of a human technological competence perhaps six times as great. Had that upward leap in technology taken place all at once, it would have been vastly more than enough for us to escape from the Malthusian trap. Sixfold higher incomes would have pushed nutrition standards and life expectancy way up and infant mortality way down. But we did not get the sixfold technological dividend from -3000 to 1500 all at once. instead, technology crawled forward, at an average pace of perhaps 4% per century.

In the absence of patriarchy the risks might well not have been nearly as dire: A population reproducing itself plus a little more would have left you with only a 1/9 probability of having no surviving child, a much lower risk. But Geha′zi and Elishi in the year -875 are not discussing whether the wealthy Shunamite woman has surviving daughters, nieces, or even nephews, but only that she does not have a son.

“Ensorcelled by the Devil of Malthus”—that was the fate of the typical human in the long agrarian age. The logic is simple: as food production increases, so does population; as population increases, so does demand for food; as demand for food increases, so does pressure on resources; as pressure on resources increases, so does scarcity; as scarcity increases, so does poverty; as poverty increases, so does mortality; as mortality increases, so does population decline; as population decline occurs, so does food surplus; as food surplus occurs, so does population recovery; and the cycle repeats itself. Thus this Malthusian cycle kept us at a constant level of “subsistence”. This level of “subsistence” did vary substantially across time and space, depending on cultural factors. But we guess that the typical human standard of living in the agrarian age was roughly $2.50/day.

How confident are we of this? Quite confident. One of the main sources of evidence is anthropometric data: the measurement of human body size and shape. People in the agrarian age were short, really short: perhaps four inches shorter than we are today. That means substantial malnutrition during individual human growth. And population growth was really low: 2% per generation, and we know that a nutritionally unstressed preindustrial human population typically doubles every generation. That means substantial malnutrition during life: immune systems so compromised as to be unable to fight off even small infections, and women so skinny that ovulation is hit-or-miss.

Slow technological progress—perhaps 4% per century. Slow population growth that, through smaller farm sizes and more additional other forms of resource scarcity, more-or-less offset any effect of better technology on living standards—figure 2% population growth on average, 8% per century. Very strong pressures to devote resources to having more sons, at least where High Patriarchy ruled—and, in the Old World, at least after the year -3500, it did rule across all of Eurasia and down Africa from the north to the tsetse fly belt. Brutal nutritional scarcity and poverty—figure typical lifespans of 25 years, income levels of $2.50/day, more than half of a typical family’s resources going to the uncertain provision of their 2000 calories plus essential nutrients a day, and people’s adult heights stunted relative to ours by four inches or more.

Thus in such an agrarian-age world there was no possibility of humanity baking a sufficiently large economic pie for everyone, or nearly everyone, to have enough. Micah the prophet talked about the utopia to come “in the latter days” when the Storm God of the Semites would “judge between many peoples”, and so “they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks… they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree, and none shall make them afraid…” (Micah 4:1-4 RSV). But, given the level of technology relative to population and hence resource scarcity in the agrarian age, there simply could not be enough vines and fig trees.

Dealing with the Fig-Tree Shortage

So what were the consequences in the -3000 to 1500 bronze and iron agrarian ages of this general human vine-and-fig-tree shortage? Of the fact that technology, resources, fertility, and population placed humanity near to a Malthusian equilibrium, in which there was no possibility of humanity baking a sufficiently large economic pie for everyone, or nearly everyone, to have enough?

how then do you get enough for yourself, and for your family?

You could be lucky, and be born in a time when the resource-human numbers balance was exceptionally good: just after a big plague would work; so would be being part of a civilization bringing technologies that were previously unknown in a piece of land to that land—Greeks and Phoenicians settling Marseilles in -700, or Puritans settling Massachusetts in 1650.

You could become, yourself, exceptionally productive. Working hard to become extraordinarily productive relative to the norm would be very difficult. Plus, if you succeeded that merely made you a soft and attractive target for people pursuing a different strategy for getting enough for themselves, a strategy that turned out to be the dominant strategy.

What was that dominant strategy.

It was to join a gang. It was to become a member of a gang of thugs-with-spears (and, later, gunpowder weapons), their bosses, and their tame accountants, bureaucrats, and propagandists—and perhaps a few specialists in craftsmanship and in logistics as well. Such an élite basing its power on violence and propaganda could find a way to collect a sufficiently large share of the ecojnomic pie for its members and their families to have enough. To do so, they would need to find a way to elbow competing gangs of candidates for élite status out of the way, and then successfully run their force-and-fraud, exploitation-and-domination game on the rest of the population.

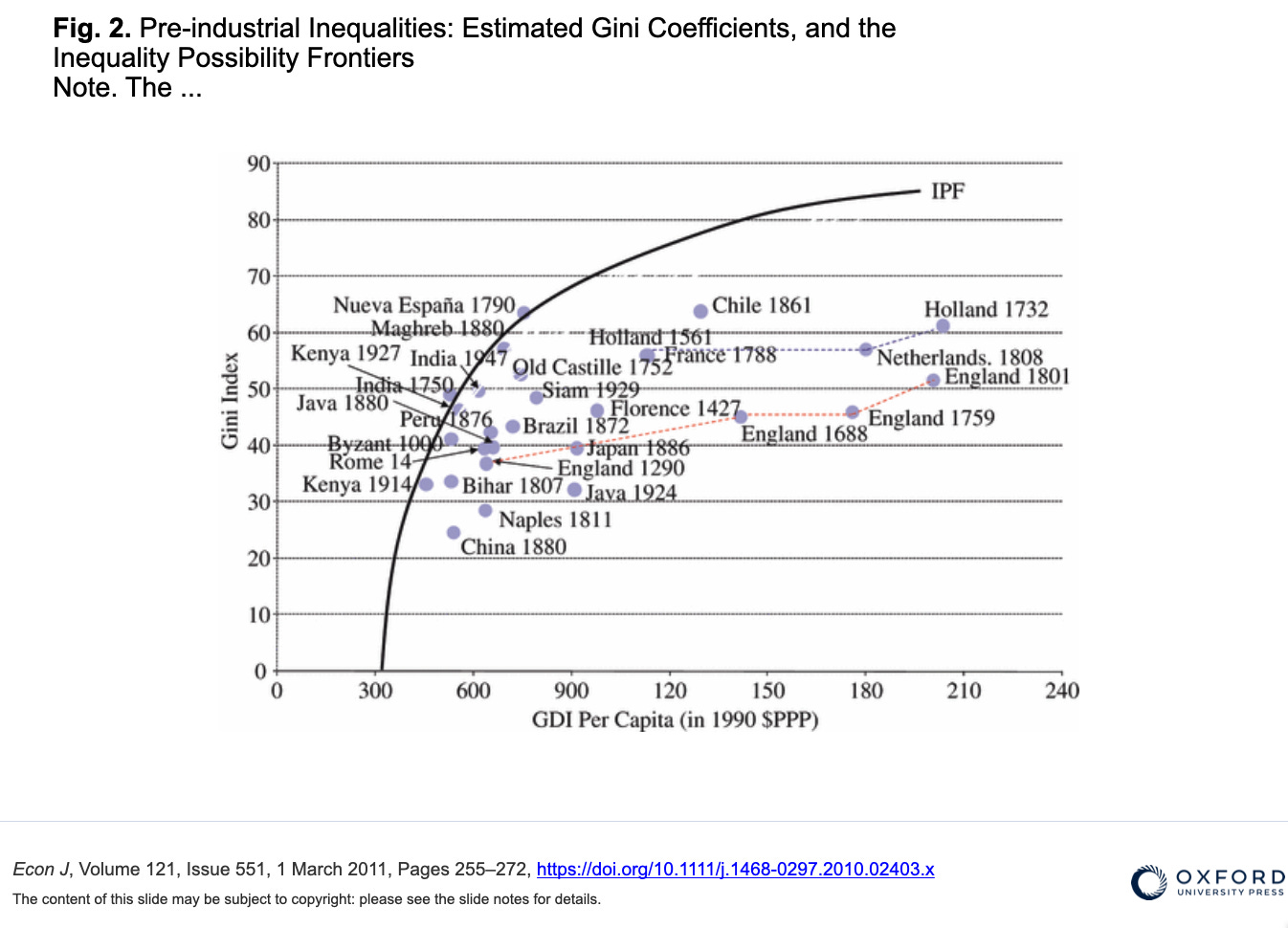

It appears to be a fact about human history that the rule was for societies to find themselves under the domination of such an élite. Lindert, Williamson, and Milanovic surveyed what we know. They conclude that pre-industrial agrarian societies were, typically, almost as unequal as they could possibly have been. There is a maximum feasible deviation from equal distribution: it is the level of inequality at which, given the level of average productivity, if inequality had been any higher, the bulk of the population would have been unable to reproduce their numbers in the next generation. Pre-industrial societies’ inequality levels are between 60% and 100% of that maximum feasible deviation.

Thus “modes of domination” were more important than modes of production in the bad-old agrarian economy days. There are three dimensions of these modes of extraction most worth noting:

The extraction-status dimension: slavery, serfdom, & lesser degrees of status unfreedom.

The general within-society across-household inequality dimension: ghe degree of plutocracy.

The gender dimension: patriarchy

Consider Aristoteles of Stageira, sometime tutor of King Alexandros III “The Great” Argeádai of Makedon. For 2000 years, from the moment he became the favored pupil of Plato up until call it the year 1650, and in a long arc from Ireland to India, Aristotle was THE Philosopher.

Capital P.

THE definite article.

If you said “the philosopher”, you were referring to Aristotle. And people did. He was “the master of those who know”, as Florentine poet Dante Alighieri named him in his Divine Comedy.

Aristotle’s main discussion of what we callteconomics comes in the book we call the politics. The Politics is about how prosperous and wealthy Greek men organize themselves and their inferiors into city-states that provide an arena and support for life and, of course, for the practice of philosophy. The first book—actually, for him it was the first scroll—Of the politics is about economics, or rather resources and household management, because unless resources and the households Controlled by prosperous and wealthy Greek men Are present and well organized, successful organization of a city state, of a polity, will be impossible.

In the first book of his Politics, Aristotle talks about the necessity of owning slaves. It is, in fact, The first thing on his mind when he talks about managing resources on the part of the household—Greek oikos, household, and Greek nomos, organization or management. Hence oiko-nomos. Hence economics.

THE Philosopher says:

Let us first speak of master and slave…. The management of a household… [needs] property... A slave is living property.… If every tool could accomplish its own work, obeying or anticipating the will of others, like the statues of Daidalos, or the tripods of Hephaistos, which, says the poet Homer, “of their own accord entered the assembly of the Gods”; if, in like manner, the shuttle could weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, then chief workmen would not need servants, nor masters slaves…

The tripods of Hephaistos are self-propelled catering carts. From Homer’s Iliad:

Thetis of the silver feet came to the house of Hephaistos,

Imperishable, starry, and shining among the immortals,

Built in bronze for himself by the god of the dragging footsteps.She found him sweating as he turned here and there to his bellows

Busily, since he was working on twenty tripods

Which were to stand against the wall of his strong-founded dwelling.And he had set golden wheels underneath the base of each one

So that of their own volition they could wheel into the immortal

Gathering, and return to his house: a wonder to look at.These were so far finished, but the elaborate ear handles

Were not yet on. He was forging these, and beating the chains out.

As he was at work on this in his craftsmanship and his cunning,Meanwhile the goddess Thetis of the silver feet drew near…

But, observed Aristotle, he did not live in such a Golden Age, in which music could be played and cloth woven without human hands. He, Aristotle, did not have robot blacksmiths or the self-propelled serving trays that could both keep the food warm and decide when it should be brought into the dining room, things that myth attributed to the lifestyles of the heroic and divine. Since he did not have these, Aristotle, or any other Greek man who wanted to lead a leisurely enough life to have time to undertake philosophy, and play a proper role in the self-governance of the city-state, needed to own and effectively boss slaves.

And not just one or two slaves either, but household slaves, agricultural slaves, craftworker slaves, and many more.

That was the rule for civilizations—and, to a substantial degree, for hill-country or desert-country people who saw themselves as opposed to corrupt, brutal “civilization”. It is not clear to me—with one important exception—that agrarian-age societies can be ranked one way or another with respect to complexity and luxury of the élite going with or against less degraded lives for the non-élite.

States were (and are) more than often highly, highly coercive. But so, often, were not-states. A strong state can mobilize more power to coerce. But a strong state can also mobilize more power to protect non-élite individuals from roving bandits and the stationary bandits who are local notables. A state has an interest in an imperial peace, a sophisticated division of labor, and a social climate that boosts investment—all so that there is stuff it can tax—on a scale that local notables and roving bandits definitely do not.

Thus I think it is difficult to make the argument that it is in general worse to be under the hegemony of a state than to be under the hegemony of a local powerful lineage. Is one’s life more constrained by hegemony in Edinburgh, near Rosneath Castle, or around Castle Hill Henge? There is also a powerful argument that it was better to be a free farmer in the Seine or the Thames valleys under the Dominate of the successors of Diocletian in the 300s than to be a thrall of some Saxon or a serf of some Norman adventurer-thug 250 or 600 years later.

But there is one exception I see: There is a very strong, indeed irrefutable, argument that where mercantile (and later industrial) capitalism get tied to staple plantation production for the market and with slavery things get very, very bad indeed very very quickly.

But, in general, when you find an agrarian society in which some élite class of people are enjoying a life considerably better than one in which they spend more than half of their resources on their 2000 calories plus essential nutrients a day and spend considerable time thinking about how hungry they are—when you find such a class, they have their comfort by being THE gang that is running their force-and-fraud, exploitation-and-domination game on the rest of society. They are gathering where they did not scatter. They are reaping where they did not sow.

Thus, as I see it, all players with social power and autonomy here—the Persian aristocracy headed by the king-of-kings, the Spartiates, and the Athenian citizens—have autonomy and social power by virtue of their success at being an oppressive, resource-extracting oligarchy.

But given that, there are things to admire and things to understand in the ways that these oligarchies organized themselves, and in the use that they made of their social power and material resources. Yes, they are dominating the peasants, craftsmen, and laborers. Yes, that extractive domination can be extremely cruel or less cruel. But when we look within the élite of any society, its own interrelationships can be more or less brutal and more or less unjust themselves.

We can cheer for Sennacherib’s defeat by plague in his unjust war on Judah. And yet it remains the case that the Davidic dynasty was also a hard master just as the Kings of the World, Kings of Assyria were: “My father [Solomon] scourged you with whips, I will scourge you with scorpions”, said David’s grandson Rehoboam. And indeed it was, as Samuel had warned, a bad thing to have a king:

Samuel: ‘He will take your sons and appoint them to his own chariots and horses, to run in front of his chariots. He will appoint some for himself as commanders of thousands and of fifties and others to plow his ground, to reap his harvest, to make his weapons of war, and to equip his chariots. And he will take your daughters to be perfumers, cooks, and bakers. He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive groves and give them to his servants. He will take a tenth of your grain and grape harvest and give it to his officials and servants. And he will take your menservants and maidservants and your best cattle and donkeys and put them to his own use. He will take a tenth of your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves. When that day comes, you will beg for relief from the king you have chosen, but the LORD will not answer you on that day…

Within itself, the oligarchy could be rigid or flexible, cruel or less cruel, culturally creative or stagnant. And it could rule and extract resources more or less brutally. And the stories that the oligarchies tell of themselves and of their competitors are worth remembering, and there is wisdom to be gained therein—as long as you take those stories with the proper amount of salt.

The Haximanishya prince Arsama, after all, really was THE BOSS FROM HELL.

And there is—even if it unbelievably brutal in its resource-extraction force-and-fraud game—value in the oligarchy’s ability to insulate its members from arbitrary and capricious power.

Herodotus: ‘Pythios the Lydian… came to Xerxes, and said as follows: “Master, I would desire to receive from thee a certain thing at my request, which, as it chances, is for thee an easy thing to grant, but a great thing for me, if I obtain it.” Then Xerxes, thinking that his request would be for anything rather than that which he actually asked, said that he would grant it… “Master, I have, as it chances, five sons, and it is their fortune to be all going together with thee on the march against Hellas. Do thou, therefore, O king, have compassion upon me, who have come to so great an age, and release from serving in the expedition one of my sons, the eldest, in order that he may be caretaker both of myself and of my wealth.”…

Then Xerxes was exceedingly angry…. He forthwith commanded those to whom it was appointed to do these things, to find out the eldest of the sons of Pythios and to cut him in two in the middle; and having cut him in two, to dispose the halves, one on the right hand of the road and the other on the left, and that the army should pass between them by…

It is just a story.

And Herodotus tells it for a reason.

And we should take it not as a true fact about Greeks and Persians, but rather on what were current ideas in –400s Athens about how an oligarchic élite should and should not conduct its affairs.

And then there is the paradox, which Herodotos plays up, of the Spartiates being free, but… not. Maintaining your freedom to do as you personally want to do is incompatible, in a sense, with marching to the beat of your different drummer. The Spartiates do not live in trembling fear of an anger-management failure by one of their kings. They do not tremble in fear that a Great King with an anger management problem might kill them and their entire families on a whim—they are not slaves of the Great King.

But they are slaves of the laws of Lykourgos, and dare not act otherwise—at least, in Herodotos’s story:

Now [Great King Khshayārsha]… sent for [exiled Spartan King] Demaratos… [and] asked… “Demaratos… declare to me this, namely whether the Hellenes will endure to raise hands against me: for… they are not strong enough in fight to endure my attack…”

He inquired thus, and the other made answer and said: "O king, shall I utter the truth in speaking to thee, or that which will give pleasure?" and he bade him utter the truth, saying that he should suffer nothing unpleasant in consequence of this, any more than he suffered before.

When Demaratos heard this, he spoke as follows: "O king, since thou biddest me by all means utter the truth…. Which I am about to say has regard not to all, but to the Lakedemonians alone: of these I say, first that it is not possible that they will ever accept thy terms… they will stand against thee in fight… whether it chances that a thousand of them have come out into the field, these will fight with thee, or if there be less than this, or again if there be more."

Khshayārsha hearing this laughed, and said: “Demaratos, what a speech is this which thou hast uttered, saying that a thousand men will fight with this vast army!… If indeed they were ruled by one man after our fashion, they might perhaps from fear of him become braver than it was their nature to be, or they might go compelled by the lash to fight with greater numbers, being themselves fewer in number; but if left at liberty, they would do neither of these things”….

To this Demaratos replied: “O king, from the first I was sure that if I uttered the truth I should not speak that which was pleasing to thee…. Thou didst compel me…. The Lakedemonians are not inferior to any men when fighting one by one, and they are the best of all men when fighting in a body: for though free, yet they are not free in all things, for over them is set Law as a master, whom they fear much more even than thy people fear thee…. They do whatsoever that master commands; and he commands ever the same… not [to] flee out of battle from any multitude of men, but stay in their post and win the victory or lose their life….

Khshayārsha turned the matter to laughter and felt no anger, but dismissed him with kindness…

So, yes, I cheer for the Greek resistance. And I think a great deal was at stake at Salamis and Plateia, and that it really did matter and was significantly for the better that the Hellenes won those two battles. And so I think there is no warrant to block us from telling Herodotos’s and Steven Pressfield’s story of Thermopylai.

Neverthless, there is the one more thing that is important: We should never forget those at the base of society who did much work and suffered much poverty, and that the stories of the élite from Achilles and Odysseus on down are stories of a group of people who were, at base, thugs with spears—plus their tame accountants, bureaucrats, propagandists, luxury artisans, and courtiers.

Who built the walls of seven-gated Thebes?

In the books you will find the name of kings.

Did the kings haul up the lumps of rock?

And Babylon, many times demolished.

Who raised it up so many times?

In what houses Of gold-glittering

Lima did the builders live?

Where, the evening that the Wall of China was finished

Did the masons go?

Great Rome Is full of triumphal arches.

Who erected them?

Over whom Did the Caesars triumph?

Had Byzantium, much praised in song

Only palaces for its inhabitants?

Even in fabled Atlantis

The night the ocean engulfed it

The drowning still bawled for their slaves…

Dear good man Brad. How the hell do you do this (and everything else)? Kindly distribute those surplus lobes of neural capacity that must swell out of your cranium.

For me, it's #4 which is the best reason not to tell the tale of Thermopylae as Herodotus tells it. But I also think there's an element of #3 as well: Thermopylae is just not that important. Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea were important and we should tell that story, leaving Thermopylae as a footnote.